“With ‘Valerian’ I have all the advantages of a series without the disadvantages. Thanks to Christin’s scripts and the space-time dimensions of science fiction, I can break every mold and tell a radically different story each time.” — Jean-Claude Mézières

He could have been an accountant like his father. Instead, Valerian artist Jean-Claude Mézières was drawn into the world of art at a very young age. “My only pleasure is drawing something I’ve never drawn before,” he says. As soon as he could hold a pen, he was scribbling. When he became a teenager, he sent a first draft of a comic book to Tintin creator Hergé. The master responded, “Continue!” So he did.

Surly and stubborn

Today the drawings of Valerian are universally acclaimed. Many insiders, like French science-fiction writer Gerard Klein, admire the “constant surprise, the diversity, and the thematic and visual richness” present in his work.

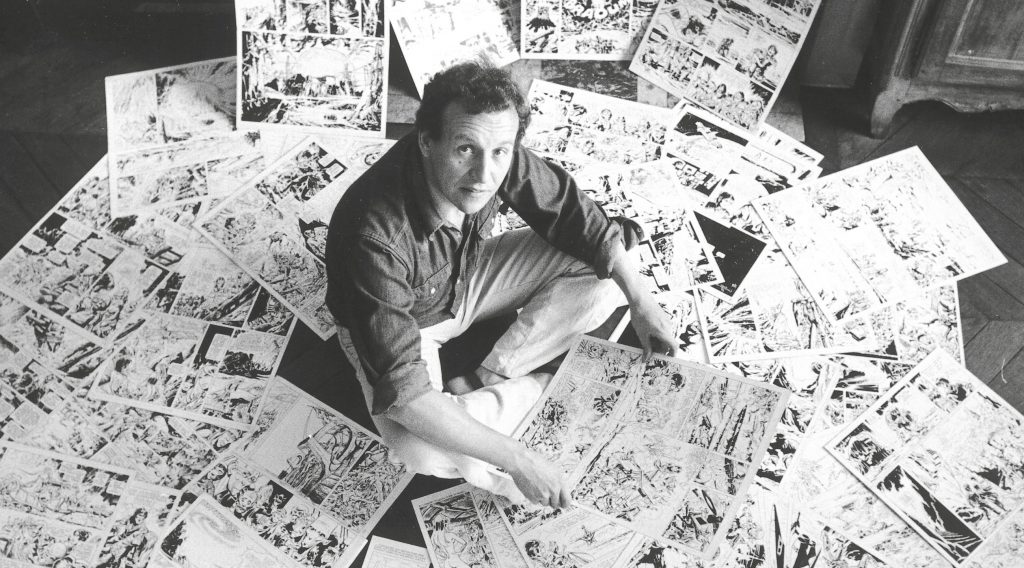

It’s true. But it has been nothing but effort to get there. Valerian co-creator Pierre Christin, who knows Mézières better than anyone, recognizes that his collaborator “advances and delivers in pain.” An open, kind, and fun-loving person in real life, Mézières is surly and stubborn at the drawing board. “My drawing board is like a battleground,” he says. “Mistakes, erasures, trial and error. It’s a labyrinth of lines.”

For Mézières, drawing has never been effortless. “I often redo the first pages. The Valerian ‘motor’ never gets going on the first attempt. I try something, then I try something else, and then there’ll be a moment when it finally starts moving forward.” Of course, part of the difficulty Mézières faces when working has to do with the artist’s own high expectations.

A dynamic duo

After 40 years of intense collaboration, Christin is still in awe. “Working with him is a challenge! He needs countless stages of prep work in order to get ready. Then, once the script arrives, the arguments start: ‘It’s too long,’ ‘There are too many characters,’ ‘It’s not the right sequence!’”

What follows is a long period that could be described, at best, as a joint effort. At worst, it’s like an arm wrestling match that lasts until the two finally come to an agreement about the characters and the core of the narrative. Mézières is adamant about his technique. A comic book isn’t a simple accumulation of juxtaposed drawings. What counts is the tempo, the movement. As he explains, “Christin is the dialogue writer and scriptwriter. But I’m the director.”

Despite their struggles and creative pain, the creators have two things in common: hard work and determination. Christin recognizes that “Mézières lets nothing go and never compromises. I have never seen him give up when faced with a challenge.” Or as Mézières puts it, “I only see my faults. I’m continually restarting the machine.”

How do you draw something that doesn’t exist?

In the artist’s defense, the work involved is certainly vast. Compared to many of his peers, who often rely on reams of documentation and detailed source material, Mézières’ work is particularly challenging. How do you draw something that doesn’t exist?

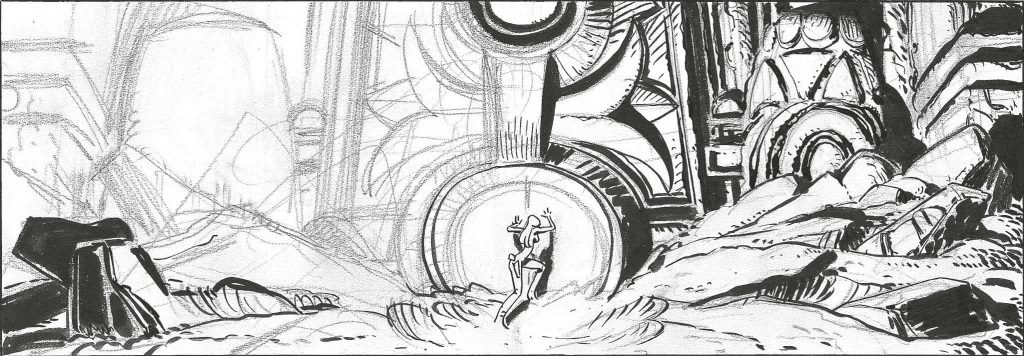

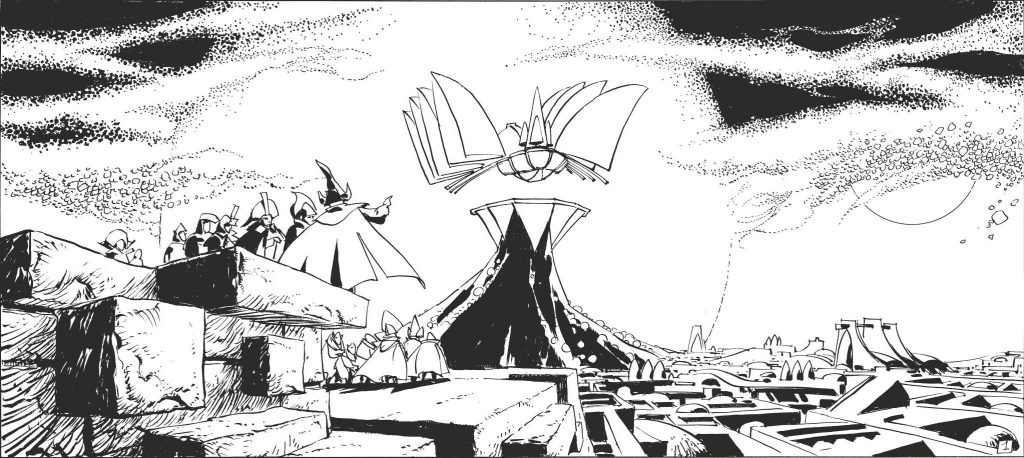

“I panicked from the first frame of Les Mauvais rêves (Bad Dreams),” remembers Mézières, referring to the very first story of the series, which appeared for the first time in album form in the recent omnibus edition put out by Dargaud (Cinebook in English). “Pierre had simply written, ‘Do a nice big image of the megalopolis.’ Right! How do you represent Galaxity, ‘Point Central’ or any of the thousand other planets, like Solum, the star that’s continually sinking into itself and forming new strata? How do you draw an extraterrestrial, a plant, an animal or the landscape of a planet no one has ever seen? What does a ‘goumoun,’ a ‘furutz’ or a ‘zypanon’ look like?”

The problem isn’t one of reproduction but of invention. “In imaginary worlds,” he says, “nothing is horizontal or vertical or round by default. We have to try everything and often start from scratch.” When questioned on his methods, Mézières doesn’t respond immediately. But the answer finally comes: it’s primarily a question of character. “I don’t like copying photos or images that can be found online, something that happens a lot in comics.”

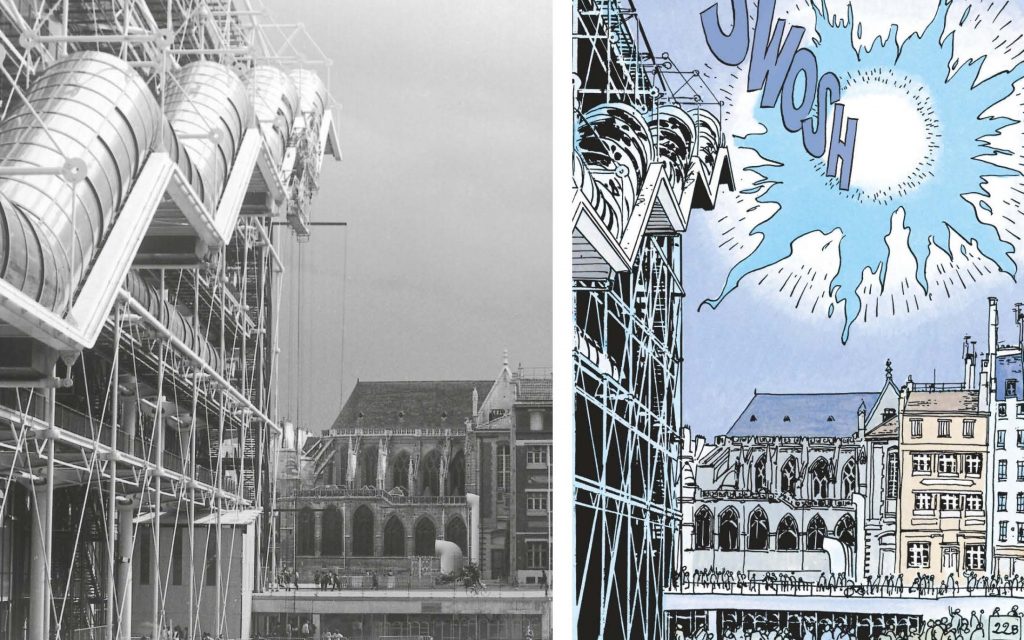

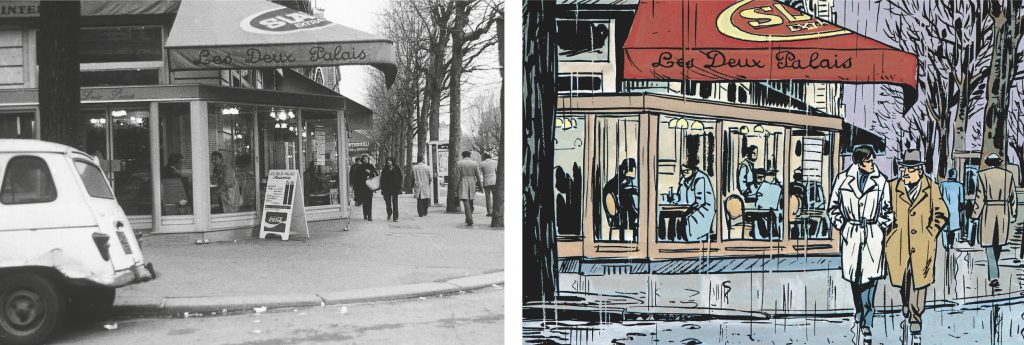

For him, reality can be suffocating. Copying annoys him. Even though he sometimes makes exceptions (for example, the innumerable times the Parisian metro station Châtelet shows up in his work—see below), for Mézières, freedom is what counts most in his drawing. Imagination comes first. This is perhaps fundamental to his personality. The love of wide open American spaces, which we know have profoundly influenced his life (see: “Valerian – The Birth of a Saga“), seems to match his love of the empty page where everything is yet to be written. “I love these moments of adventure, on the hunt for an idea, a character or an element of the scene’s décor.”

Châtelet metro station: A space-time blend

At the end of 1977, when Mézières was putting the finishing touches on Heroes of the Equinox (Dargaud 1978, Cinebook in English 2014), he saw an advance screening of what was then a curious little sci-fi film called Star Wars at the Metz Science-Fiction Festival. The imagery was straight out of a traditional American sci-fi novel, and also reminded him of the universe of… Valerian. Especially the volume The Empire of a Thousand Planets (Dargaud 1971, Cinebook 2011), which had already been out for several years (see: “Valerian — A Model for Star Wars“).

This is probably what led him to suggest to Christin that they add a touch of contemporary, earthly realism to their favorite imaginary galaxy, starting with the streets of Paris…

He might not be aware of it, but Mézières belongs to a race of explorers and pioneers. We admire him for who he is: a splendid visionary, a subtle illuminator of the unknown. It’s Christin, the man of text and words, who is the first to pay tribute to him: “I’ve often been dazzled when I’ve seen how he’s transformed my storyline into images.”

Us too, Pierre. Us too.

This article is part three of a five-part series on Valerian, in honor of the release of Luc Besson’s blockbuster Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets in 2017. Text by Stan Barets. Originally published in Valérian l’intégrale #3 and Valérian l’intégrale #4 (Dargaud 2016-2017). Header image © Christin & Mézières / Dargaud.

READ PART 2: Valerian: Director and Creators Speak

UP NEXT: We explore the infinite charm of Laureline, so much more than a simple partner!