Comics have been emerging and evolving across Europe since the start of the 20th century, but it was in French, under the term bande dessinée or “BD,” that these creations started taking more and more space in the cultural landscape, alongside American comics and Japanese manga. Where do things stand now? Do “European” comics exist today? Is it possible to define a kind of “European” comics? These were the questions asked of an international panel of experts and professionals during this year’s Angoulême Comics Festival. Europe Comics invited Thierry Smolderen (Gypsy, Ghost Money), Thomas Ragon (Dargaud, France), Klaus Schikowski (Carlsen Comics, Germany), Pawel Timofiejuk (Timof Comics, Poland), Paul Gravett (Graphic Novels: Everything You Need to Know, 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die), Mike Kennedy (Lion Forge, USA) and Matteo Stefanelli (Napoli Comic Con, Italy) to discuss.

In the introduction, moderator Matteo Stefanelli pointed out that we were living at a time of globalization in comics publishing, which gives new opportunities to European publishers and artists to reach a new global audience. However, this is not a new phenomenon, as European comics have quite a long tradition of globalization. As an example Matteo recounted the story of an Italian publisher with Jewish origins who had to flee fascism in Europe and settle in Argentina. During the 1950s the publisher started importing comics and invited Hugo Pratt and other comics artists from the Venice area to come and create in Argentina. The publishing house founded as a result, Editoria Abril, was a major success, and indeed started the Argentinian comics industry, as there was no such activity in Argentina before this small European invasion.

Matteo also pointed out that during the 1920s or 1930s a large number of comics were produced by Catholic papers and were spread through the Church abroad. While in the UK in the 1950s and 1960s the non-humoristic comics (i.e. romance comics, adventure comics, war comics etc.) were produced by Italian and Spanish studios and agencies.

After the introduction the panelists were asked to name core elements that, in their opinion, could describe the European comics culture today. The very first element identified by Thierry Smolderen became one of the main themes throughout the following discussion. All panelists agreed that in Europe the production of comics is very author-oriented. The authors are the originators of ideas and it’s the authors who do most of the creative enterprising for their projects. In the US or Asia, on the other hand, the comics industry is product-driven, with editors being the main producers of ideas. Thomas Ragon and Mike Kennedy agreed, adding that comics publishing in Europe is very book-oriented in comparison to the market in the US. As Mike also indicated, there are almost two separate comics markets in the US: the book market, and the direct market where publishers sell floppies. What’s more, the latter is dominated by Marvel and DC Comics, with company-owned characters, which again is a strong contrast to Europe. However, Mike noted that the book market in the US is also growing, and there are more and more original creations released by publishers such as Image Comics.

Meanwhile, Klaus Schikowski addressed the evolution of style within European comics. After years of holding up Hergé and the “ligne claire” artists as role models with stories concentrating on adventure and humor, today’s European comics scene has evolved into a wide variety of drawing styles and story subjects. According to Klaus, the term “graphic novel” had a lot to do with bringing many new people and their own stories to comics. Paul Gravett continued on the idea that one cannot easily encompass the term “Euro comics” as opposed to the more clear picture of what defines “Manga” or “American comics.” With 28 countries in the EU alone, the continent is bursting with various distinct elements, formats and cultural references that make it difficult to group them together. Paul continued by suggesting that it is certainly a challenge not being able to impose a clearly defined “Euro comics” label on the world. Instead it comes down to individual works finding their audience outside their culture. Pawel Timofiejuk fairly summed up these ideas into naming “originality” as the core element of European comics. Pawel added that the European market is not only original, but also open and growing. Thomas illustrated the statement with the mention of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis which is a best-selling European comic book created by a non-European creator.

Matteo went on to ask the panelists about the feedback they receive from readers living outside Europe as well as non-European publishers buying translation rights. Thomas suggested that the art always comes first, and its strength is in its detail and generosity. Pawel pointed out that not that many Polish comics have yet been translated and published in countries outside Poland. The feedback Pawel often gets when showing works of Polish artists outside Poland is that the stories might be quite unusual for certain markets, but with very high-quality art. This, according to Pawel, is one of the reasons many Polish artists go on to work for American or Franco-Belgian publishers. Meanwhile Mike, as a rights buyer, noted that when promoting one of Lion Forge’s translated books, not much emphasis is put onto where the book came from. As Mike explained, Lion Forge wants the work to stand on its own, without highlighting its country of origin.

Matteo continued on that premise by asking the publishers whether they considered the translation aspect and the sale of rights when working on new projects. Klaus responded by saying that he would love to, however it all comes down to the vision of the author as was discussed at the very beginning of the panel. However, Klaus also pointed out that there are now a number of accomplished creators who work in that mindset. He gave an example of German comics creator Reinhard Kleist, who took his work into a more international direction instead of creating stories based in Germany. Thomas shared Klaus’s sentiment by pointing out that there are so many aspects to consider when creating a book (story, art, production, distribution etc.) that the international appeal of the work is not always the first thing editors consider. Although editors are very aware, especially with non-fiction graphic novels that are trending at the moment, that international appeal is what the foreign rights department of each publishing house is expecting from creators and editors. As a comics writer, Thierry stated that he works in two opposite directions. With titles such as Gypsy or Ghost Money that have been translated abroad Thierry created adventure sci-fi stories which were not necessarily geographically marked. On the other hand, the graphic novels Thierry created with Alexandre Clérisse (Atomic Empire, Diabolical Summer) take place on the French Riviera or in a small French village, so as to give the books a certain “French touch.” And while being specifically based in France, these stories still enjoy international success.

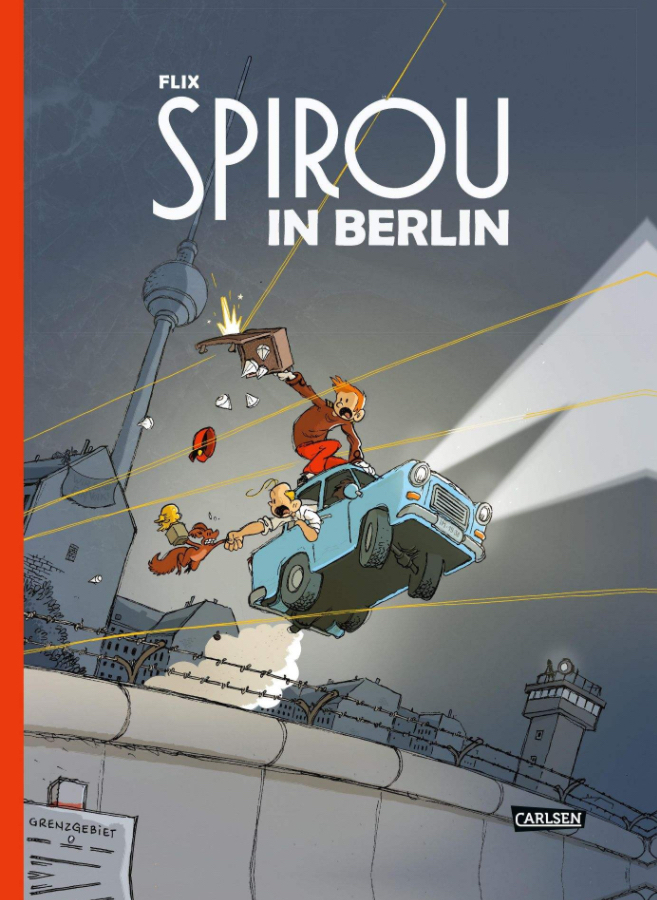

The takeaway from this part of the discussion was that the European comics panorama is highly composite. As a result, Matteo’s last question for the panelists was whether they think this fragmentary picture of the market was a barrier to European comics developing internationally and whether anything could be done on the governmental level to promote European comics abroad. Thomas immediately agreed by drawing a parallel with the government funding of European cinema and the success it’s been enjoying worldwide. He also suggested that a comparison should be made with the licensing scene in the US and Asia, and that comics should be considered an intellectual property that could become a film, or another type of license that could subsequently bring money to all parties involved. And that is why EU-supported projects such as Europe Comics are so necessary. Pawel also agreed that cooperation within the European market and support from EU institutions is important as it would help smaller markets like Poland, Germany or Turkey to show their work to bigger international markets. Klaus also looked at the question from the inside and highlighted the success of Spirou in Berlin, where the established Franco-Belgian character Spirou was brought to life by the German creator Flix. This cooperation between France, Belgium and Germany was important to all parties as prior to Spirou in Berlin, Spirou was not a well-known character in Germany.

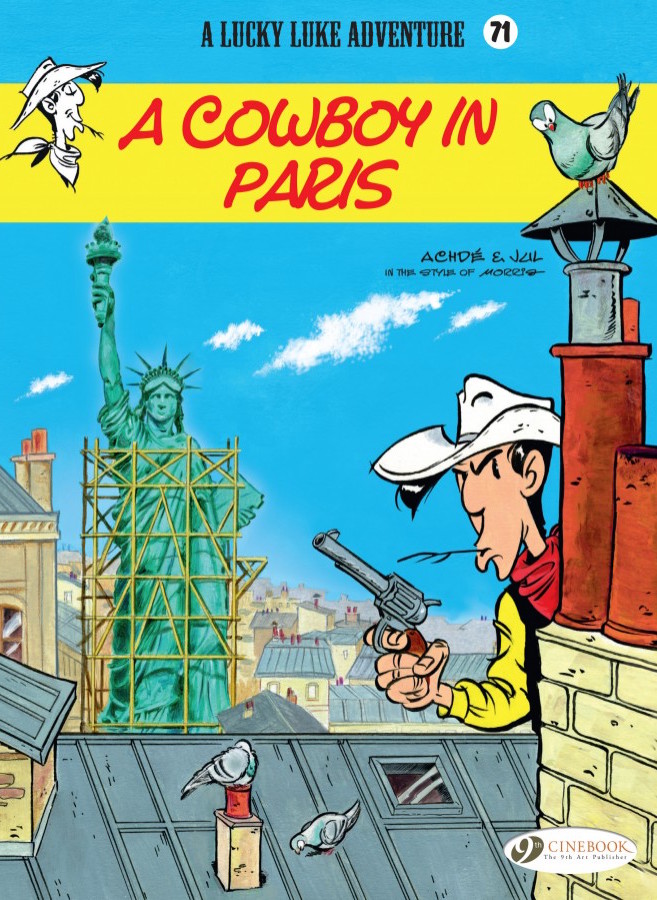

On the other hand, Mike, as a rights buyer, did not see the fragmentation of the European comics market as an issue, as festivals like Angoulême make it easy for rights buyers to meet editors and artists and to find the right material for their catalogs. Mike did agree that European publishers could profit from more collaboration, with co-productions and co-editions (such as Lucky Luke: A Cowboy in Paris as noted by Thomas, which brought together Dargaud, Cinebook, and Egmont) bringing more opportunities.

It was pointed out from the beginning of the panel that the question asked was quite broad, with no straightforward answer. However the discussion provided an opportunity for everyone involved to put together fragments of the answer. And as Matteo stated at the end of the panel while summing up the discussion, European comics is perhaps less a brand than an attitude. You can watch the recording of the panel here.