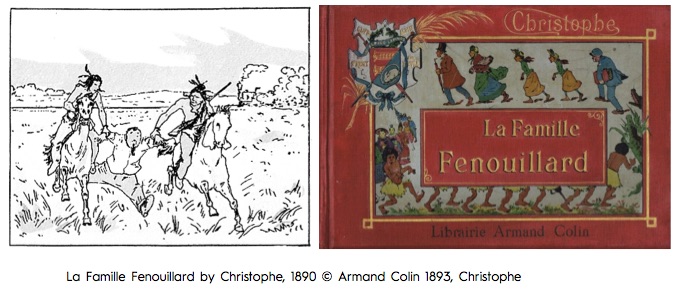

The Western is essentially an American genre: an American genre due to its subject matter, its history and its culture. That is why the early interest of European comic strips in the Wild West is somewhat surprising. However, in 1890 already, La Famille Fenouillard by Christophe, published in France, appropriated this mythology with an exotic adventure in Sioux country.

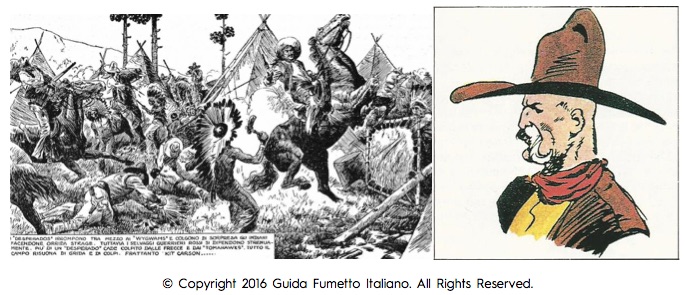

In 1931, it was the Belgian Tintin who embarked on a voyage to the other side of the Atlantic for the album entitled Tintin en Amérique (Tintin in America, Egmont UK). And in 1937, it was the Italian Rino Albertarelli who grasped the genre with the historic character Kit Carson in the magazine Topolino (the Italian Mickey Mouse magazine).

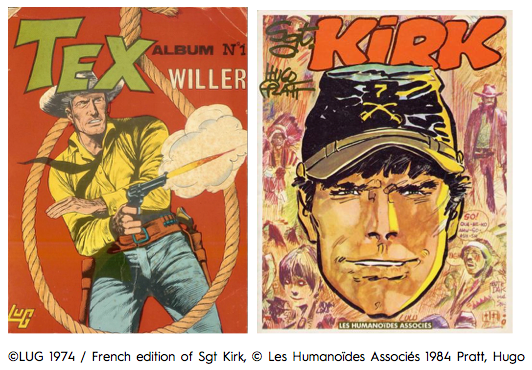

An ageing, realistic and tired man, the author’s Kit Carson anticipates the figure of the cowboy as portrayed in the later films of the 1950s. The series was taken up again from 1939 onwards by other cartoonists and would later become an institution, but Albertarelli’s dark and melancholic Wild West left its imprint on his Italian successors, from Luigi Bonelli (Tex Willer, a cowboy who would soon seek the assistance of … Kit Carson!) to Hugo Pratt (Fort Wheeling, Sergeant Kirk or the cynic Jesuit Joe).

After the Second World War

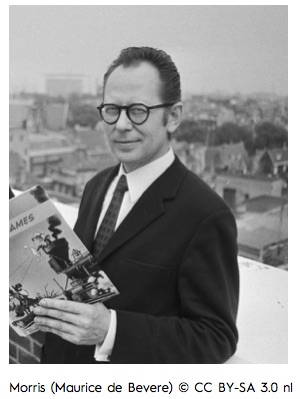

Only following the Second World War did the Western take a creative leap in Europe. Well, a leap… Perhaps it was only the fruit of one single man’s passion: the Belgian Maurice De Bevere, known as Morris. As a lover of cinema and a huge fan of American comics in his teenage years, Morris was self-taught and dreamt of becoming an animator in a cartoon studio – which is clearly revealed in his drawings. Morris imagined a fantastical Wild West for the Belgian comics magazine Spirou at the end of 1945 and in early 1946. Taking up the character traits of singing cowboys from the pre-war period, Lucky Luke became one of the spearheads of the magazine even though Morris had some doubts and was still seeking a style that would take another good ten years to establish. From Europe, it was impossible for him to document himself properly on the history of the United States and he quickly set out for the other side of the Atlantic in the company of his mentor Jijé and his best friend André Franquin. Morris stayed there for six years, four of which he spent in the Big Apple haunting libraries in order to enrich his knowledge of the Wild West and the United States. During these years abroad, he made important encounters. First of all, in 1950, he became friends with René Goscinny, a young French scriptwriter who would become the genial creator of Asterix a few years later. Through him, Morris also met Harvey Kurtzman and the whole team of the future Mad Magazine. With them, he started to work on caricature and pastiche – a revelation for the Belgian author! From that moment on, Morris knew what his European cowboy would be made of. He would be documented – but more importantly, funny and even more fundamentally, aloof. The formula: Lucky Luke would ride off alone into the setting sun at the end of each adventure, riding his trusty steed and whistling “I’m a poor lonesome cowboy”. Jolly Jumper, his faithful mount, loves to mock and philosophize (and even if Lucky Luke does not hear him, he understands him). As to his opponents, they are mythical figures from the history of the Wild West: the Dalton Brothers, Billy the Kid, Calamity Jane, Jesse James… The hero’s companions, such as Rantanplan, “the dumbest dog in the Wild West”, parodied the classics of the genre (Rin Tin Tin in this case). In this style, Lucky Luke had no competitors. It must be said that funny Westerns were not an easy genre to create… For this reason, alongside it, realism slowly gained ground.

Taking up the character traits of singing cowboys from the pre-war period, Lucky Luke became one of the spearheads of the magazine even though Morris had some doubts and was still seeking a style that would take another good ten years to establish. From Europe, it was impossible for him to document himself properly on the history of the United States and he quickly set out for the other side of the Atlantic in the company of his mentor Jijé and his best friend André Franquin. Morris stayed there for six years, four of which he spent in the Big Apple haunting libraries in order to enrich his knowledge of the Wild West and the United States. During these years abroad, he made important encounters. First of all, in 1950, he became friends with René Goscinny, a young French scriptwriter who would become the genial creator of Asterix a few years later. Through him, Morris also met Harvey Kurtzman and the whole team of the future Mad Magazine. With them, he started to work on caricature and pastiche – a revelation for the Belgian author! From that moment on, Morris knew what his European cowboy would be made of. He would be documented – but more importantly, funny and even more fundamentally, aloof. The formula: Lucky Luke would ride off alone into the setting sun at the end of each adventure, riding his trusty steed and whistling “I’m a poor lonesome cowboy”. Jolly Jumper, his faithful mount, loves to mock and philosophize (and even if Lucky Luke does not hear him, he understands him). As to his opponents, they are mythical figures from the history of the Wild West: the Dalton Brothers, Billy the Kid, Calamity Jane, Jesse James… The hero’s companions, such as Rantanplan, “the dumbest dog in the Wild West”, parodied the classics of the genre (Rin Tin Tin in this case). In this style, Lucky Luke had no competitors. It must be said that funny Westerns were not an easy genre to create… For this reason, alongside it, realism slowly gained ground.

From dark realism to savagery

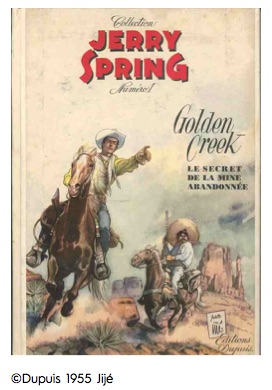

In 1948, the French Marijac, a specialist in cowboy adventures since the 1930s, wrote the story for Sitting Bull, one of the first major comic strips presenting Indians in a respectful tone (albeit his Jim Boum did not show any kindness towards them) two years before the famous film by Delmer Daves, Broken Arrow, was released. In 1954 in Belgium, Jijé created Jerry Spring for the Spirou Magazine. This Tom Mix-type of cowboy, half realistic and full of humanism, had difficulty in establishing itself but laid the path for a number of Franco-Belgian creators, beginning with Jean Giraud (later known as Moebius), a student of Jijé’s. At the time, Western films were in vogue. The greatest French critics wrote about them and made of them “the film genre par excellence”. Car

Boum did not show any kindness towards them) two years before the famous film by Delmer Daves, Broken Arrow, was released. In 1954 in Belgium, Jijé created Jerry Spring for the Spirou Magazine. This Tom Mix-type of cowboy, half realistic and full of humanism, had difficulty in establishing itself but laid the path for a number of Franco-Belgian creators, beginning with Jean Giraud (later known as Moebius), a student of Jijé’s. At the time, Western films were in vogue. The greatest French critics wrote about them and made of them “the film genre par excellence”. Car toonists followed this trend and took an increasingly pessimistic path, echoing Sam Peckinpah’s modern interpretation of the genre. The battle scenes became more and more crude, authors wrote the biographies of their characters, and graphic research shook the imagination and created an ever-increasing world of bitterness and violence.

toonists followed this trend and took an increasingly pessimistic path, echoing Sam Peckinpah’s modern interpretation of the genre. The battle scenes became more and more crude, authors wrote the biographies of their characters, and graphic research shook the imagination and created an ever-increasing world of bitterness and violence.

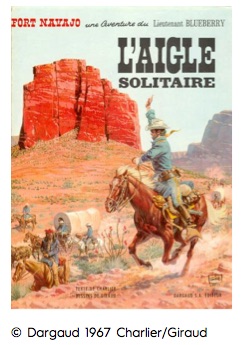

Blueberry, by Giraud and Charlier, then Comanche by Greg and Hermann, both published in France, reflect this evolution up to the 1970s. But with the continuing war in Vietnam, viewpoints changed. The Dutch author Hans Kresse, for example, started to praise the courage of the Indians vis-à-vis the first invaders in Les Peaux-Rouges (The Red Skins).

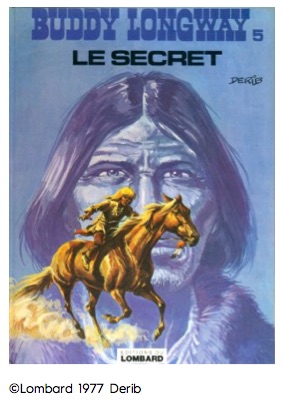

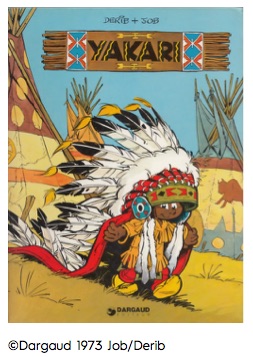

With the same feeling of solidarity, the Belgian Derib, already author of the naturalist Buddy Longway (published by Cinebook) and of Yakari (Cinebook), a tender series aimed at a younger audience, devoted to the Indian issue a double cycle resembling anthropology through the crossed paths of a medicine man taken in the genocide of the preceding century (Celui qui est né deux fois/ The Man Born Twice), and of his great grandson, one hundred and fifty years later, dealing with the drama of contemporary rese rvations (Red Road). At the same time, influenced by The Great Silence by Italian Sergio

rvations (Red Road). At the same time, influenced by The Great Silence by Italian Sergio

Corbucci, at the beginning of the 1980s, the Durango series by Swolf reclaimed Sergio Leone’s cinematographic codes, following the path of the Spaghetti Western genre alone. Soon, André Juillard, author of the famous French saga Les Sept Vies de l’Épervier (The Seven Lives of the Sparrow Hawk), created the follow-up to the series on the American continent, Plume aux vents. Here, he addressed the delicate issue of white women kidnapped and assimilated by the Indians. However, the Western genre was slowly falling into disuse…

The post-modernism of the new cartoon

With the emergence of the “new cartoon” in Europe, the Western was also shaken by a kind of post-modernism. Th e French Christophe Blain and David B. have committed to the genre since 1997 with Les Aventures d’Hiram Lowatt & Placido, where the aesthetics and interpretation had much more in common with Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man than with the Hollywood revival. Christophe Blain returned to the genre alone a few years later with the series Gus, a true homage to the character Lucky Luke and traditional Westerns. Only one difference: here, the heroes were too laid back to be gangsters and were often busy flirting with girls instead of preparing their train and bank robberies. In 2016, Lucky Luke is celebrating his 70th birthday, reminding us that a step to the side is always necessary for European authors who choose to embark into the Western genre, an American genre par excellence that, paradoxically, is more popular on this side of the Atlantic than in its birthplace.

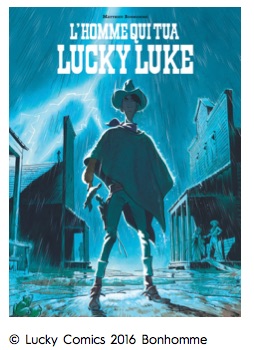

e French Christophe Blain and David B. have committed to the genre since 1997 with Les Aventures d’Hiram Lowatt & Placido, where the aesthetics and interpretation had much more in common with Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man than with the Hollywood revival. Christophe Blain returned to the genre alone a few years later with the series Gus, a true homage to the character Lucky Luke and traditional Westerns. Only one difference: here, the heroes were too laid back to be gangsters and were often busy flirting with girls instead of preparing their train and bank robberies. In 2016, Lucky Luke is celebrating his 70th birthday, reminding us that a step to the side is always necessary for European authors who choose to embark into the Western genre, an American genre par excellence that, paradoxically, is more popular on this side of the Atlantic than in its birthplace.  Matthieu Bonhomme and his recent L’Homme qui tua Lucky Luke (The Man Who Killed Lucky Luke, Europe Comics 2016) are an excellent example of this. Intelligent, personified, sliding into the interstices left empty by the myth of Lucky Luke, Bonhomme reconsidered the hero’s decision to stop smoking (from one day to the next, in order to allow their export to the United States, the cowboy’s cigarettes were replaced by a blade of grass in Lucky Luke albums as from the mid-1980s, against a backdrop of protests). Such is the paradox of the Western in Franco-Belgian comic strips: far from its original territory, the Wild West is reinvented with a distance and freedom that the Americans themselves could never have allowed. After all, this is fairly normal: the European Western – and this is where all its charm lies – is living proof of enthusiasm that only passions that are condemned to remain a fantasy know how to galvanize.

Matthieu Bonhomme and his recent L’Homme qui tua Lucky Luke (The Man Who Killed Lucky Luke, Europe Comics 2016) are an excellent example of this. Intelligent, personified, sliding into the interstices left empty by the myth of Lucky Luke, Bonhomme reconsidered the hero’s decision to stop smoking (from one day to the next, in order to allow their export to the United States, the cowboy’s cigarettes were replaced by a blade of grass in Lucky Luke albums as from the mid-1980s, against a backdrop of protests). Such is the paradox of the Western in Franco-Belgian comic strips: far from its original territory, the Wild West is reinvented with a distance and freedom that the Americans themselves could never have allowed. After all, this is fairly normal: the European Western – and this is where all its charm lies – is living proof of enthusiasm that only passions that are condemned to remain a fantasy know how to galvanize.

By Stéphane Beaujean, Artistic Director of the Angoulême International Comics Festival

Translated from the French: Barbara Angerer