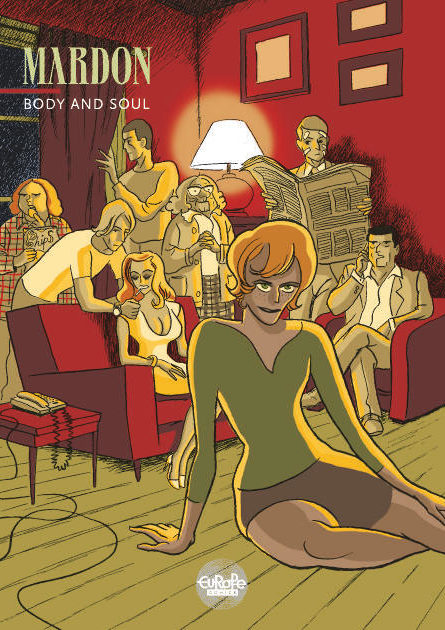

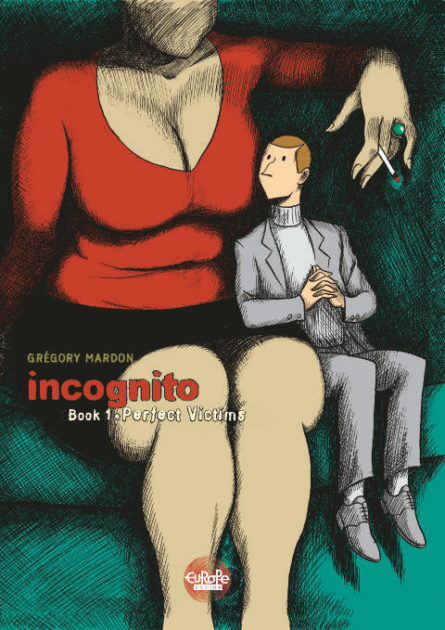

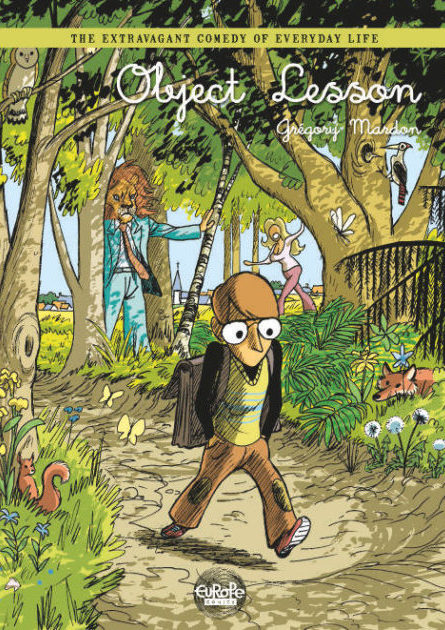

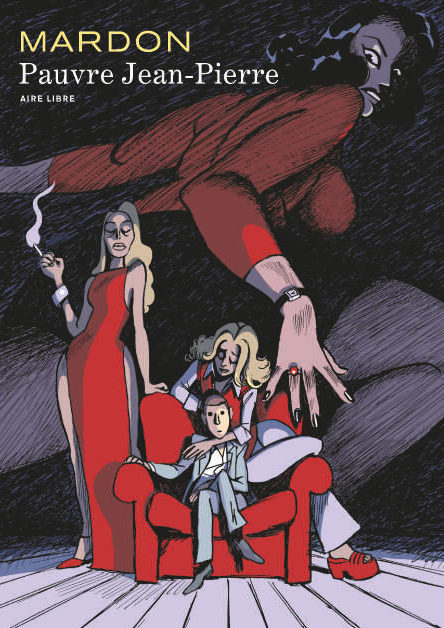

Grégory Mardon’s Body and Soul, Incognito, and Object Lesson set the tone for a body of work that has been enthralling audiences for the past fifteen years, with versatile poetry that dips into all genres, from noir to crime, from erotica to sci-fi, from romantic comedy to historical epics, from comics to heroic-fantasy. A great explorer of the human condition, Mardon portrays the individual in a way that speaks of the universal. His dialogue is lively and effective, his pacing rhythmic and fluid, and his style adapts to the content, becoming in turn voluptuous, bucolic, or spare. Following the release in 2017 of Pauvre Jean-Pierre (“Poor Jean-Pierre,” from Dupuis), a three-book collection composed of the aforementioned titles, Mardon looks back on his career and talks about the artist’s life.

The human comedy… of genre

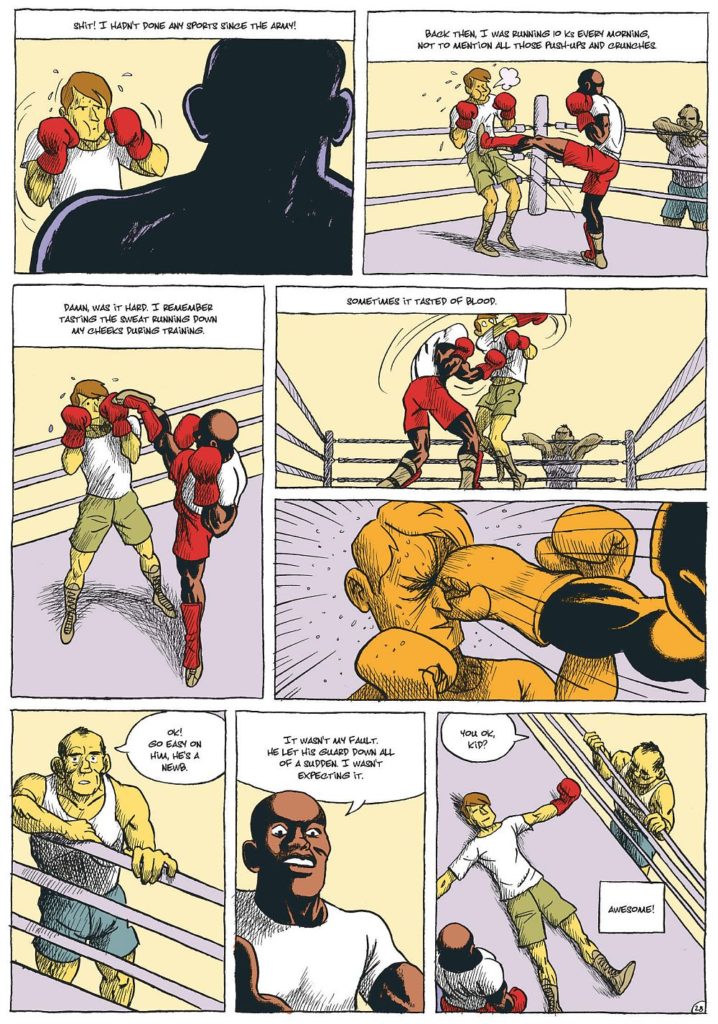

“Just like John Irving, who starts writing as soon as he begins to empathize with his characters, I need to feel compassion for mine,” begins Mardon. His favorite theme is the difficulty of self-love, of understanding each other, and of communicating. Broken relationships, the vagaries of marriage, the waxing and waning of feelings, death, deceptively simple life full of obsessions, uncertainties and aspirations—these are the issues he explores in his ironic, affectionate, and offbeat universe, often dark, sometimes violent, but always steeped in humanity. He deftly exposes the true personalities behind his characters’ masks, the artifice and the facades. His stories are based on what he has experienced or observed, and he populates them with unsaid words and unsatisfied souls that long for more, conveying the relationship game with tremendous sincerity.

As he also loves fiction and adventure, Mardon takes a sly pleasure in twisting realism “to turn it into something more exciting, more spectacular.” And that’s precisely what the genre of books he is so fond of allow him to accomplish. However, type-cast in spite of himself as a slice-of-life writer and chronicler of the everyday, Mardon struggles to get his numerous publishers to appreciate just how much he enjoys changing worlds: “People are much more complex than what they want to show. What interests me is to observe human beings, be that via a snapshot of contemporary life, a medieval tale, an erotic narrative set in the ‘30s, or a dreamlike fable about travel. Genres allow me to create very personal stories and detach myself from my everyday world. I can hide behind that.”

Poor Jean-Pierre

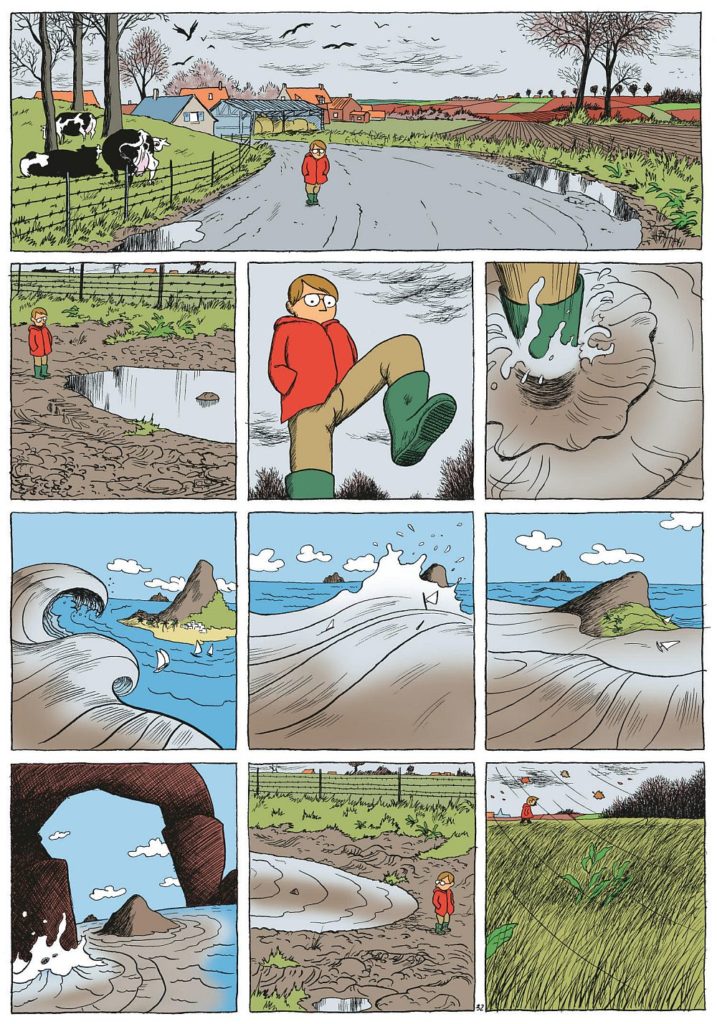

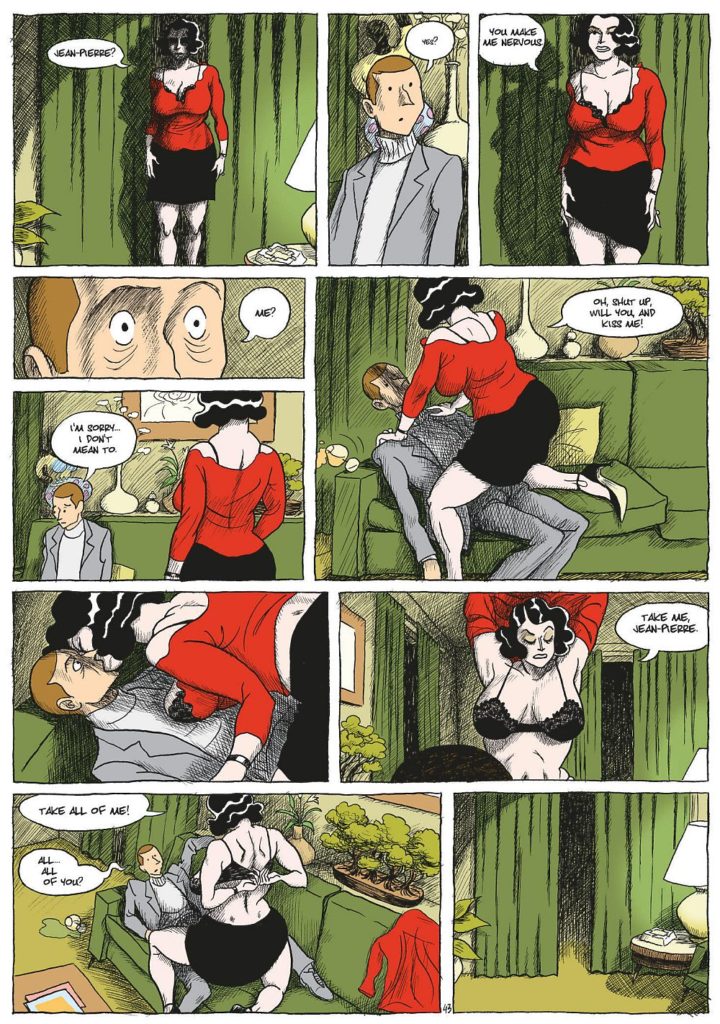

“There are so many people around us who don’t look like anything special,” says Mardon, “and then one day, boom, you learn that something extraordinary has happened to them.” Such is the case of Jean-Pierre Martin, the main character of the trilogy. Jean-Pierre is a discreet young man who considers himself invisible and insignificant. “He lacks self-confidence, but he hasn’t given up. He dreams of feeling alive but remains unshakably reasonable. And so, in an effort to live intensely, to have experiences and to fill up a life that he finds monotonous, he tries to jump start things, to provoke excess, outrageousness and imbalance in his life. A nostalgic and melancholy character, he feels alone and dissatisfied. He complains about it yet wallows in it at the same time. And maybe he puts women a little too much on a pedestal.” The thread linking the three books in the collection is not chronological: “The third book is about the childhood of Jean-Pierre and his friend Cyril, but all three explore the same themes: the extraordinary and the poetry of everyday life. Men, women, loneliness, the impossibility of fully understanding each other, love, death, separation, loss, lightness of being, and the settings of both Paris and the countryside.”

Object lesson

“I come from a modest background,” says Mardon. “I grew up in the countryside in the north of France, near Arras. I’m the oldest of three brothers. There was a big age gap between us, so I had a rather lonely childhood.” In this way, the nameless little paths, the puddles that make waves, the frozen and desolate fields on which crows descend, the time of day when the cows return to the stable, and the feeling of isolation are among the things Mardon depicts with rare accuracy—along with the brutality of cockfighting, the slaughtering of animals, and the sacrificed cats, the chained-up dogs or decapitated ducks.

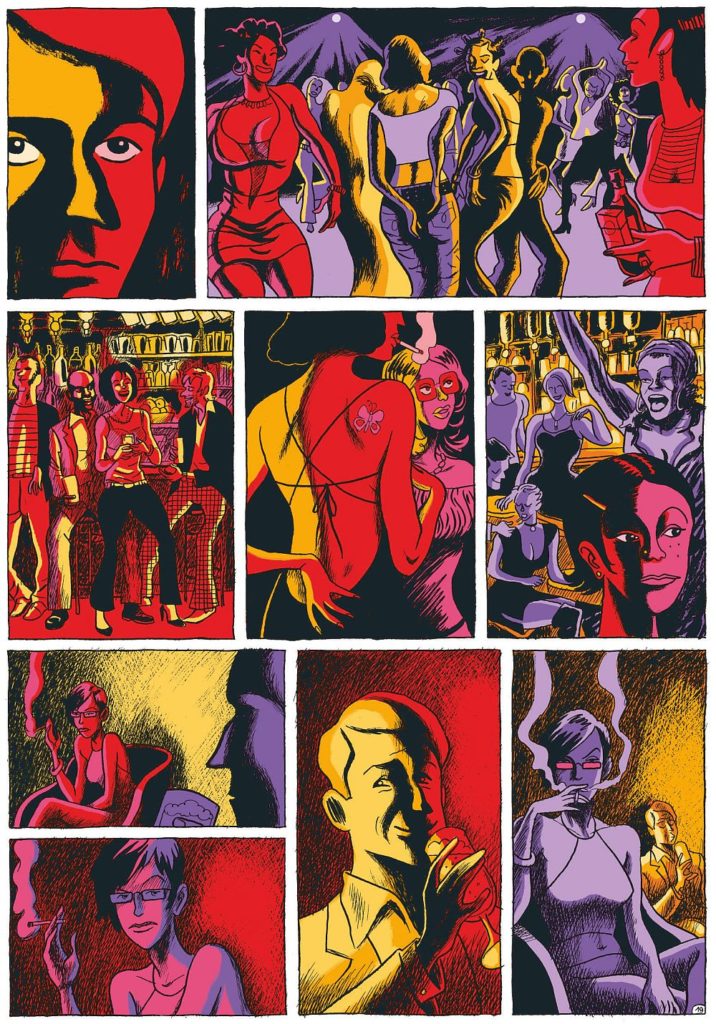

These are memories he shares with Jean-Pierre and that we find in Object Lesson, the third book in the collection. His recollections include school of course, which is where Jean-Pierre first meets Cyril, who goes on to become his lifelong friend and who is much more comfortable with girls and with life in general. He also symbolizes friendship itself, thus linking the three books in a common thread. When they get older, in fact, the two buddies head to Paris together, where the women are elegant and determined. High heels that click as they walk, fleeting smiles, blazing hues of hair, and generous shapes… the ghosts of Fellini seem to haunt these visions, and Jean-Pierre feels overwhelmed by so much femininity. He has no idea how to approach these visions, unlike Cyril, who easily and casually piles up the conquests.

Words unspoken

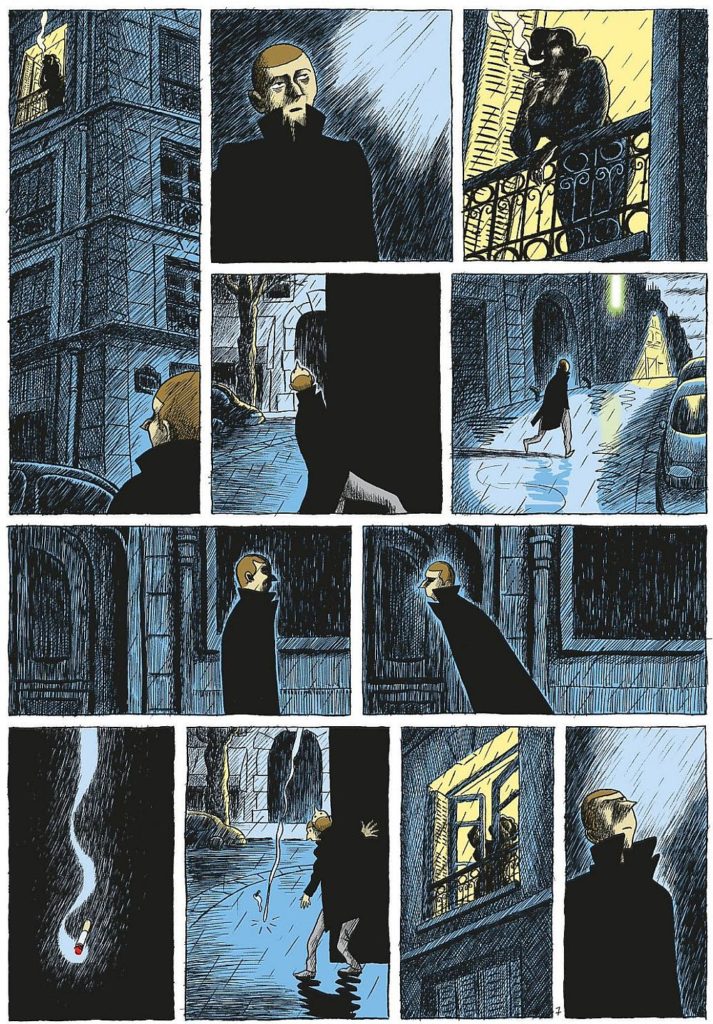

Mardon plays with discomfort, strangeness, and emotion. He favors lengthy moments in which words are no longer there but merely suggested. The silence he creates causes breaks in the rhythm, thus producing moments of great poetry: “I love words but for me, comics is an art form that can do without them. As a matter of fact, I hate Blake & Mortimer. Language is important, but once I put my script into images, I do a lot of pruning. The drawing allows me to say a lot and in a different way. I work a lot on dialogue, but what I love, actually, are the contrasts between what’s said and what’s silent, and how they reveal each other. I like to lose the reader and then grab him again, to leave him surprised or disconcerted.” Or remove the superfluous to keep only the essential. “One of [Antoine de] Saint-Exupery’s maxims has stayed with me since art school: ‘Perfection is achieved not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take out.’ I always try to avoid overloading my images, so as not to interfere with the flow of the reading. The drawing must be stripped to the point of becoming almost abstract.”

The art of narration

After studying at the Gobelins art school in Paris, Mardon started out in the field of animation, creating the scenery of several French TV series, including Papyrus, Fantomette, and Diabolik, before switching to comics, a universe he feels is more free and creative. His first published strips appeared in Spirou magazine in 1998. Vagues à l’âme, his first book, was released by Les Humanoïdes Associés in 2000, marking his official entry into the 9th art, to which he decided to devote himself full-time in 2002, with the publication of Cycloman, co-created with Charles Berberian (published by Cornelius, reissued in 2012).

“I love the language of comics,” says Mardon. “I love the form, the rhythm, the drawing, the image and the very specific way this art form tells stories. It’s an art of narration and that’s what I like.” His pantheon of classics includes Tintin and Gaston Lagaffe, followed by Corto Maltese, Manara, Moebius, and François Bourgeon’s series Les Passagers du vent (“Passengers of the Wind”). Later came the publishing house L’Association, Blutch, and Dargaud’s Poisson Pilote imprint. Nowadays he doesn’t read as much, but among his latest favorites are Camille Jourdy‘s Juliette, Morgan Navarro‘s Ma vie de réac (“My Life as a Reactionary”), and Gipi‘s La Terre des fils (“Land of the Sons”). “Before, I had my favorite authors. Now, not so much. Either that or I have too many. But as far as themes and plotlines are concerned, cinema has had just as much of an influence on me.” An influence that comes from figures like Truffaut and Pialat and, more generally speaking, mainstream French films of the ‘70s, which were often shown on television, and of course American cinema.

For his illustrations, he usually does his ink work traditionally, through wash drawing, by using a Pintel brush with ink refills, or simply using a felt tip pen before applying his colors on the computer: “I tend to get bored pretty quickly, so I try to find tricks that provide a variety of little joys and help me have fun as I draw. And while I do enjoy co-creating with another artist, I ultimately prefer doing it solo.” In addition, his working with so many different publishers is not only a function of opportunities and chance, but also because it gives him greater freedom.

The life of the artist

Despite a sustained pace of two books annually in recent years, Mardon plainly and soberly sums up his work life: “There’s a lot to say, but nowadays, above all else, it’s complicated.” After grabbing his usual coffee at a corner bistro in the Greater Paris area where he lives, the author hunkers down at his drawing table, where he remains all day and often until late at night, even on weekends, “except for those times when the writing needs to percolate.” This routine leaves him little time for anything else: “I’m not one of those people who thinks it’s absolutely essential to find complete fulfillment in your job, but I stay locked up inside anyway, because I feel guilty not working. Before, I used to get out, exercise, go to art exhibits and movies. Now all I do is watch TV. Too much of it.”

After years of being in a studio environment—alongside cartoonists, as well as animation artists—he’s been working at home since December 2016, “and it’s hard,” he says bitterly. Because, as is the case with so many comic book authors, it’s hard for him to make a decent living off his talent alone, which forces him to take on various illustration jobs, for the press and online. “I would love to live off my art and only write and draw what I want,” he says. “Experimenting and exploring other graphic or narrative approaches, constantly seeking to go beyond what I know. But just because you’re not living the life you dreamed of doesn’t mean you need to ruin the one you’re living. It’s very difficult on a day-to-day basis.” Which again brings to mind Antoine de Saint-Exupery, who said as well, “Make the dream devour your life, so that life doesn’t devour your dream.”

By Loraine Adam, press attaché for the comics festival Formula Bula (Paris) as well as numerous other events in France, and journalist at Rolling Stone France, where she covers comics every month.

Translated from the French by Montana Kane.

Header image: Pauvre Jean-Pierre (“Poor Jean-Pierre”) © Mardon / Dupuis