A vast desert, an expat novelist, and a series of murders: the perfect recipe for a gripping tale. This is what Jean-Luc Fromental and Philippe Berthet have given readers with The Other Side of the Border, a graphic novel full of action and mystery. Below, scriptwriter Fromental offers a look into the historical and geographical context that inspired his story.

Santa Cruz Valley: the westward rush

Most of the time, the Santa Cruz River is a dry riverbed. But during the moonsoon season, when abundant rainfall soaks the Sonoran Desert, it suddenly fills up and rushes through the valley. The river is about 184 miles long and takes its source in the grasslands of Arizona’s Patagonia Mountains. There, it runs southward and enters Mexico before suddenly changing course and branching off toward the northwest. Then it crosses the border in Nogales to reenter America, where it fertilizes the Santa Cruz Valley. This is where The Other Side of the Border unfolds. The river and its whims reflect well the unpredictable character of this desert land which flourishes after every flood.

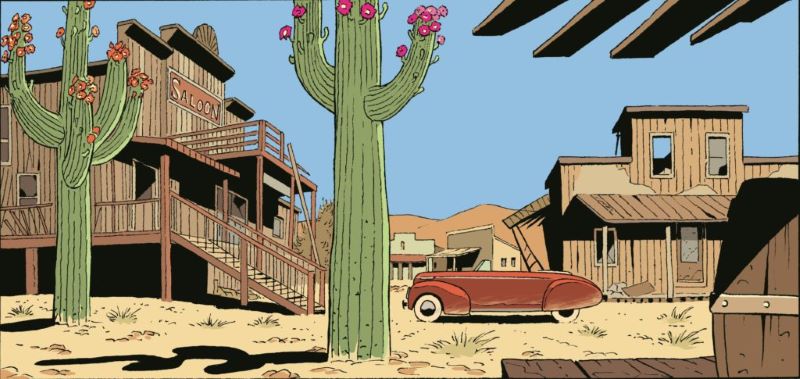

Like a lot of other Wild West territories, the settlement of the Santa Cruz Valley depended on the first settlers’ blood, sweat, and greed. They began to arrive around 1850, when the United States bought 29,650 square miles of borderlands to construct railways. It was the usual lot: landowners, farmers, prospectors, and miners come to seek the Sonoran Desert’s underground treasures. Mexican peasants who stayed on that side of the border gazed, amused, at this bustling primitive capitalism. The ranchers brandished dollars and lawyers against each other in order to extend their territories. The battle raged between breeders and farmers, free-range areas and fenced-off lands. Makeshift mining towns—soon to become ghost towns—popped up in the desert amid the cacti.

The Valley’s history can be reduced to a handful of names and influential families. The local aristocracy, like the Bouldin, Watts, or Davis clans, was busy with creating its empire and expropriating the Hispanic residents they came across. Nothing was off-limits when it came to evicting the existing occupants from the plots of land conceded by the United States to Mexico. This concession had been made in exchange for territories in southern New Mexico. The atmosphere was charged with unfairness and illegality and the law was clearly in favor of the landowning class, as was the tradition in the Wild West.

The powerful families won their legal battles, but they didn’t know what to do with the approximately 100,000 acres of fertile land they had wrested from their inhabitants in federal court. There was no gold at the foot of the Santa Maria Mountains nor oil in the Sonoran Desert. These lands thus remained an El Dorado for speculators, until they were upended by the Great Depression. In this way, early capitalism in the west met its end; it was going to need new faces and new capital to survive. Both appeared the year of the Great Crash in the form of Talbot T. “Tol” Pendleton.

“Tol” Pendleton was a former football player at Princeton University and had amassed a fortune as a Texas oil magnate after World War I. He seemed to be the first one to realize that a prestigious ranch on the edge of the desert was a more meaningful sign of nobility than an oil rig. Taking advantage of a drop in real estate prices, he bought up the old guard’s lands and created the Baca Float Ranch Company in 1932. Property speculation and tourism started to gain a foothold in the valley. Over the following three decades, Pendleton lived the lavish life of a gentleman-rancher. He imported beef cattle from Texas and embarked on the breeding of thoroughbreds. When he needed cash, he sold a few plots of land to his friends.

Luxurious ranches were blooming along the Santa Cruz Valley. The newcomers gentrified the region, which soon became the playground of the wealthy and powerful. Retired executives from General Motors put on their cowboy boots to go drink martinis with Hollywood stars like John Wayne or Stewart Granger. Those who didn’t have to exploit their lands’ resources used the property for a winter residence, or opened guest ranches for well-off customers from New York, Boston, or Los Angeles. As a newspaper of the time wrote, such clients went there to “regain contact with nature without renouncing the white man’s quality of life.”

These high-society figures brought with them their customs, needs, and vices that they wished to conceal from the rest of the world. The area’s inhabitants had long drunk to excess and taken advantage of the lax laws of the valley. However, the widespread alcoholism, arrogance, and adultery taking root in the valley were new behaviors that changed the face of the desert. A journalist of the time wrote: “Limos, station wagons, thoroughbreds, elegant homes, and private jets are all now part of local life. The captains of industry, East Coast elite, idle youth, and wealthy heiresses rule over a region that the descendants of Spanish conquistadors and American pioneers still call home.”

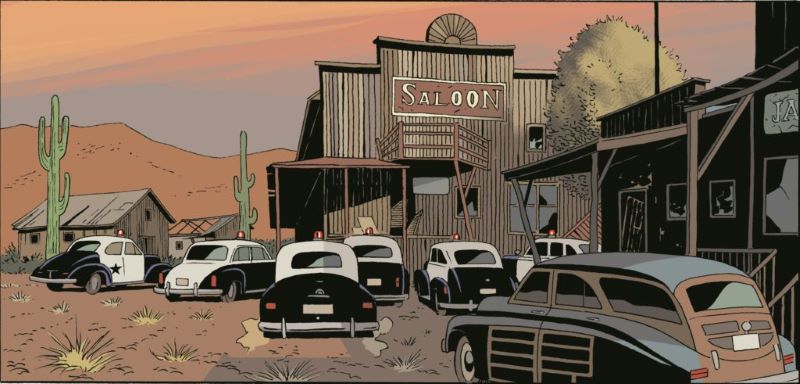

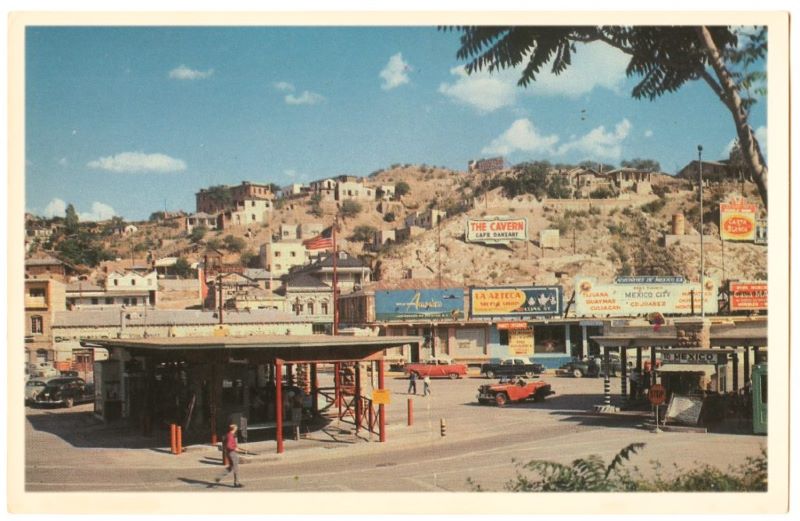

In the 1940s, “Tol” Pendleton was the very eye of this high society cyclone which devastated the valley with its alcohol-fueled lifestyle—hence the valley’s nickname, “Santa Booze Valley.” The plague spread from La Caverna, the most popular bar on the Mexican side of Nogales, to the Arizona Inn, a luxurious hotel in Spanish neocolonialist style, and from the Mountain Oyster Club, Tucson’s most exclusive resort, to private ranches at the edge of the valley.

Nogales: a tale of two countries

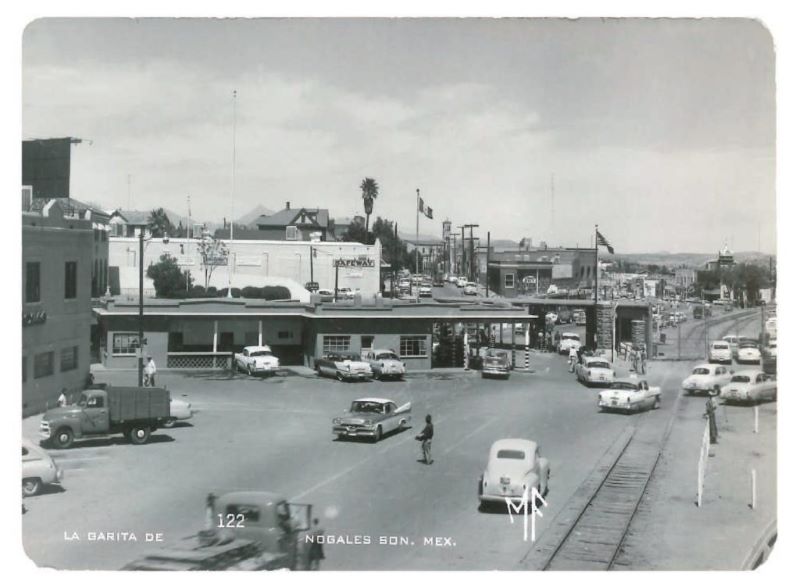

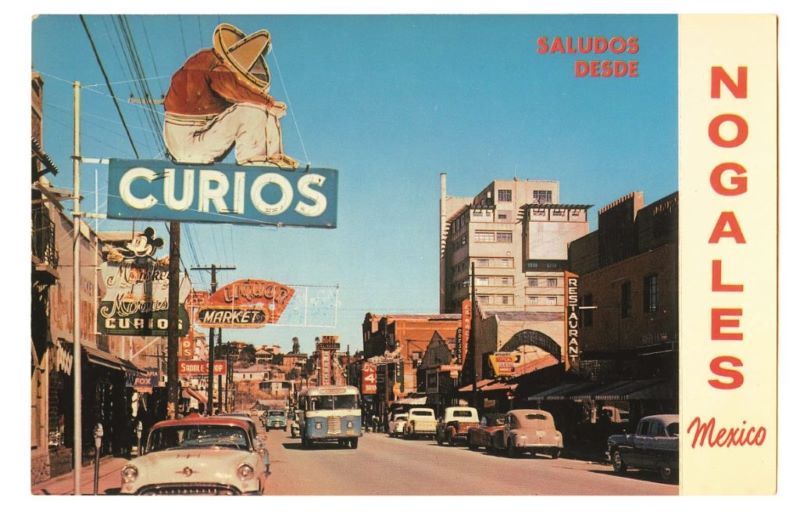

The source of this “booze river” was located in Nogales—known as “Ambos Nogales” to the Mexicans—that straddled the border. The American side was a small town, but dotted with bars, banks, and luxury stores. On the Mexican side, one found bars, but also cantinas, gambling houses, brothels, and other places of ill repute, underpinned by a dense and impoverished local population. The North’s wealth attracted southern migrants, whereas the permissiveness that reigned south of the border drew in crowds of Americans with fat wallets and an unquenchable thirst for lust. The flows constantly intersected.

Originally, no physical border separated the two sides. One side of Main Street was in Mexico and the other was in the United States. The divisions were economic and social but not yet racial. Whether they were “brown” or “white,” all the locals had to deal with the same droughts, floods, and conflicts with the indigenous peoples of the area. The need for a physical border came with the stirring of the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century. In 1914, Pancho Villa and his famous División del Norte briefly occupied the American side of Nogales. It was time to take action, and fences went up.

A writer in the desert

In May 1948, the writer Georges Simenon came into play. His extraordinary personality and eccentric lifestyle are not so far removed from the central character of The Other Side of the Border. In 1945, he had left France to come to the United States, where he initially lived in Tucson, Arizona, together with his wife Regine, his secretary Denise, his loyal housekeeper Boule, and his son Marc. He then decided to go further south and settled in Tumacacori, a city located on the Santa Cruz River’s east bank and the site of a former Franciscan mission. A thirty-minute drive from Nogales, Simenon described it as a place “where life still feels like a western.”

Denise was not only Simenon’s secretary, but also his mistress, leading to turbulence in the domestic sphere. As a result, Simenon rented two houses from “Tol” Pendleton: one for Regine, Boule, and Marc, and the other—the aptly-named “Stud Barn”—for Simenon, Denise, and their love affairs.

Simenon wrote approximately fifty novels during his ten years in the United States. Among them, about a quarter are dedicated to his observation of the New World, including some of his finest work: Trois chambres à Manhattan, La jument perdue (his first western), La mort de Belle, L’horloger d’Everton, and La boule noire.

His year in Tumacacori was fruitful, as he wrote four books: La première enquête de Maigret and Mon ami Maigret (among the best in the “Maigret” series), the classic Les fantômes du chapelier, and most notably, Le fond de la bouteille, the only one to take place in the Santa Cruz Valley. Alongside his prolific writing, Simenon occasionally gave in to the blinding lights and neon signs of Nogales. Places of ill fame, flashy cafes, feverish crowds, and exposed flesh were his raw material, a bottomless pit of ideas and inspiration for him.

Some nights, he crossed the border, alone or with Denise, to give himself over to the women and alcohol of the city’s brothels. He came home from each of his trips exhausted, disgusted, and satiated, full of the dark treasures which would adorn his stories. Simenon, the perpetual migrant, left the Santa Cruz Valley in June 1949 after having drained it of its pleasures. With his family, luggage, and weapons in tow, he set off on the next leg of his American journey. Destination: Hollywood.

He left as a parting gift Le fond de la bouteille, an unrivaled account of the Santa Cruz Valley at its peak of alcohol and excess. Ten years ahead of Orson Welles’s border town masterwork Touch of Evil.

Text by Jean-Luc Fromental. Translated from original French by Téa Bodson. Header image: The Other Side of the Border (© Berthet/Fromental; Dargaud)