Comics and comic strips have been published in Turkey for the last one hundred odd years with some interruptions, and for eighty years on a continuous basis. There have been some remarkable local productions published during this period. Yet, when comics are brought up in Turkey, the first creations that come to mind are those of foreign origin. The foremost reason for this is that comics production in Turkey has never developed into a full-fledged industry branch. Local comics that were financed and supported by newspaper publishers could not rival foreign publications, neither on a quantitative nor on a qualitative basis. Therefore it is of no surprise that even during the years 1955-1975, generally known as the golden age of comics in Turkey, no locally produced children’s comics attained widespread popularity.

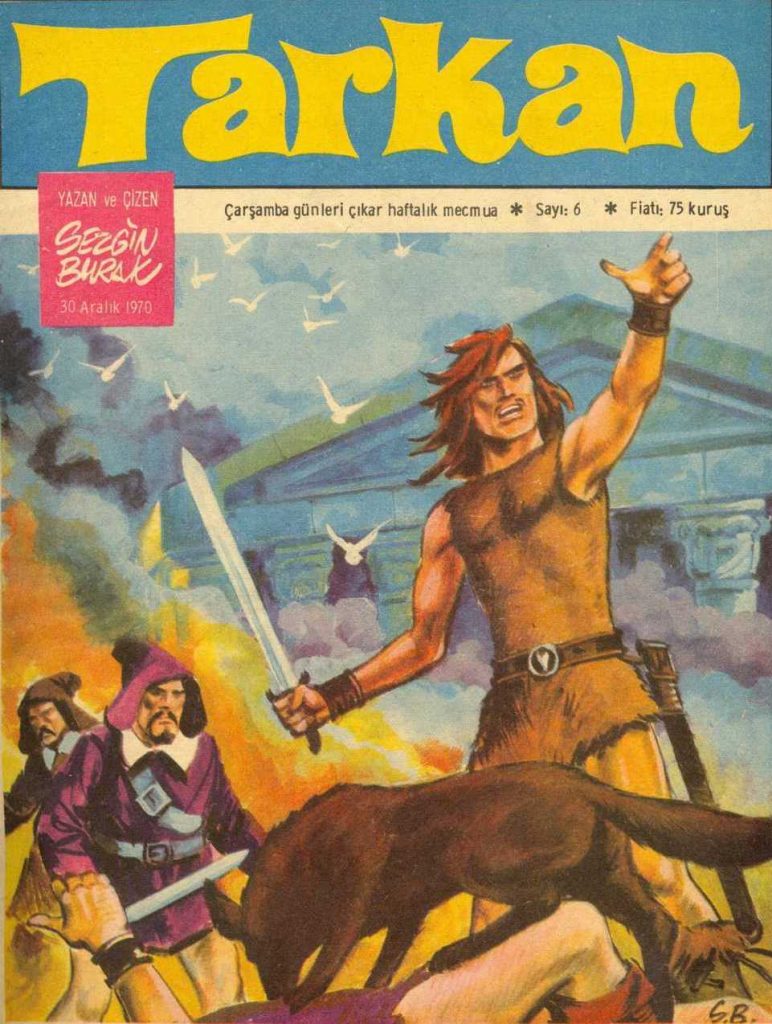

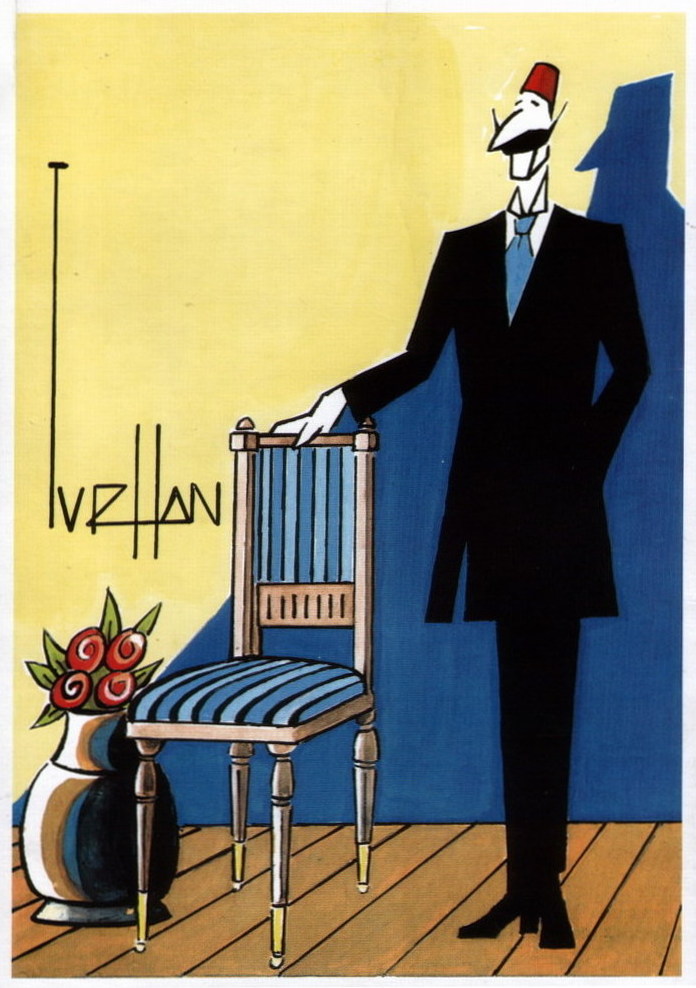

Still, the country saw the creation of many significant comics, such as Karaoğlan by Suat Yalaz, Abdülcanbaz by Turhan Selçuk, and Sezgin Burak‘s Tarkan. In this period, comics were published daily in the form of comic strips in newspapers, which would mostly be compiled in full-length comic books after their daily publication. At a time when magazines for children could survive even on small sales figures, cartoonists turned first and foremost to periodicals, thus reinforcing the presence of comics across their pages. With growing income and influence, the artists were then able to develop their work more deeply, allowing their creations from then on to incorporate narrative forms according to the needs of the publication and readers’ profiles.

Turkish authors’ focus on historical themes, extravagant prose about heroic figures, and eroticism seem to have met readers’ expectations as well as publishers’, as these elements have firmly established themselves over the years. Traditionally, almost every newspaper (Hürriyet, Milliyet, Akşam, etc.) has reserved a space for comic strips, especially historical ones. The benefits to newspapers have not come solely from the growing interest in this genre—comic strips have contributed to newspaper design on the visual level, too. Due to insufficient printing technology before the 1970s, photographs were only scarcely used. Thus, artists who worked both with the newspapers and in the comic strip genre were able to shape the visual aspect of the Turkish press. Caricatures, vignettes, portraits, illustrations and various decorations were all used in place of photographs. Comics artists (such as Suat Yalaz, Bedri Koraman, and Turhan Selçuk) generally received good salaries and the comic strips they produced returned high royalties.

With the introduction of modern printers to Turkey, however, photographs soon took over on the visual level. This transformation would reduce both the standing of comic strips within the newspaper industry as well as the royalties paid for their creation. Due to subsiding royalties, newspaper illustrators and graphic artists gradually turned their attention away from the production of comic strips, and despite the continued importance of comic strips since then, they would never again match the high level of popularity they enjoyed leading up to the 1970s.

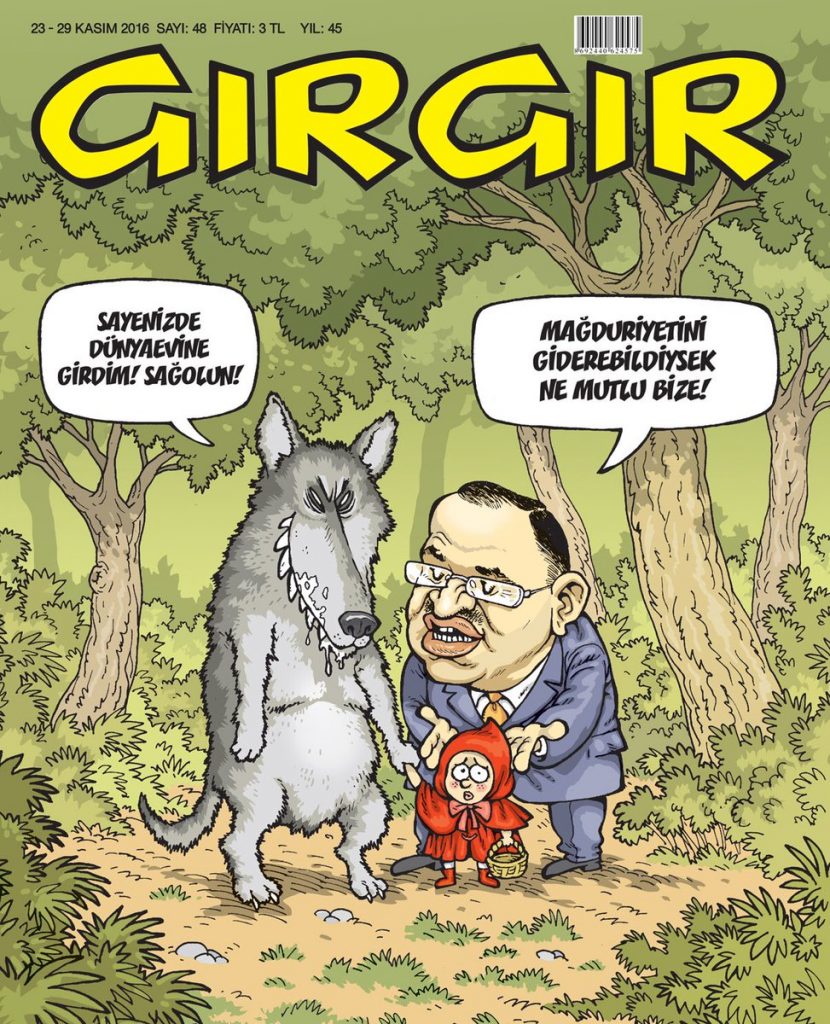

The evolution of comics in the highly popular magazine Gırgır is once again due to favorable economic conditions and the financial support from newspaper owners. It all began with the development of offset web printing facilities by famous media owner Haldun Simavi, which represented a great step forward in the evolution of print media. Up until then, it had been virtually impossible to produce hundreds of thousands of newspapers and distribute them across the entire country in a single day. But with his new, fast-printing facilities, Simavi revolutionized the press and printing industry by producing massive amounts of newspapers and magazines rich in photographs and illustrations. At the onset of the 1970s he also experimented with an erotic, comical, and to some extent political humour magazine—Gırgır. Along with its strong cultural and political identity, Gırgır’s commercial success cannot be disregarded. The emergence of many comics creators on the national level and their existence up until today is directly attributable to Gırgır’s strong sales and economic success. The magazine opened up a new path for artists who had previously been working mainly for newspapers. Many young people were able to make a good living in this way through their art, and under such favorable conditions, other magazines with the same format as Gırgır, sporting caricatures and humorous comic strips, have also become popular.

Nearly all the comics from the last forty years that have secured a place in the hearts and minds of the Turkish belong to the humor genre. The vast majority (Oğuz Aral‘s Utanmaz Adam, or “Shameless Man,” En Kahraman Rıdvan by Bulent Arabacioglu, Gaddar Davut by Nuri Kurtcebe, etc.) are based on irony, drawing heavily on exaggeratedly heroic characters and adventure-filled episodes by utilizing satirical language. Gırgır and other humour magazines (Çarşaf, Limon, Fırt) that emerged at the same time reached total sales figures of one million copies. Such a windfall of sales, as well as the magazines’ variety, had a great impact on comics, such that the richness of visual styles and narrative forms rose to an unforeseen level. Galip Tekin, Suat Gönülay, Kemal Aratan and Ergün Gündüz (Taxi Tales) were among the most productive comics artists of those years and the ones that most strongly influenced the following generations of artists.

However, such burgeoning quality and quantity was abruptly reversed by the heavy erosion of sales caused by the negative impact of television, so that by the first half of the 1990s, sales of print media had fallen by 80 percent compared with figures from just a decade before. Confronted with the growth of commercial TV channels, many magazines (Leman, Deli, etc.) turned against mainstream taste and put a new emphasis on stories that could not be aired on TV. This evolution not only marginalized magazines in general but also affected comics, investing them with a rather grotesque touch.

The most important magazine of that period was L-Manyak. The main aim of the magazine is humor and all that relates to buffoonery. Openly obscene and scatological in character, it scorns the “sensitivities” of urban society. Typical targets of the magazine are predators, braggarts, the rich, gluttons, ambitious businessmen, and those who use their sexual attraction to climb up the social ladder. As opposed to its predecessors, however, one topic is not touched upon: politics. The cover focuses on grotesque characters and comical representations of violence and various sexual practices. Decidely vulgar in nature, the magazine’s humor does however serve as constructive criticism. Mainstays of the stories in L-Manyak include the use of violence against oppression and the oppressors, the wish to escape the masses, mistrust towards certain political agendas, strong and insatiable sexual desire, hedonism, general mistrust towards others, and indifference to money.

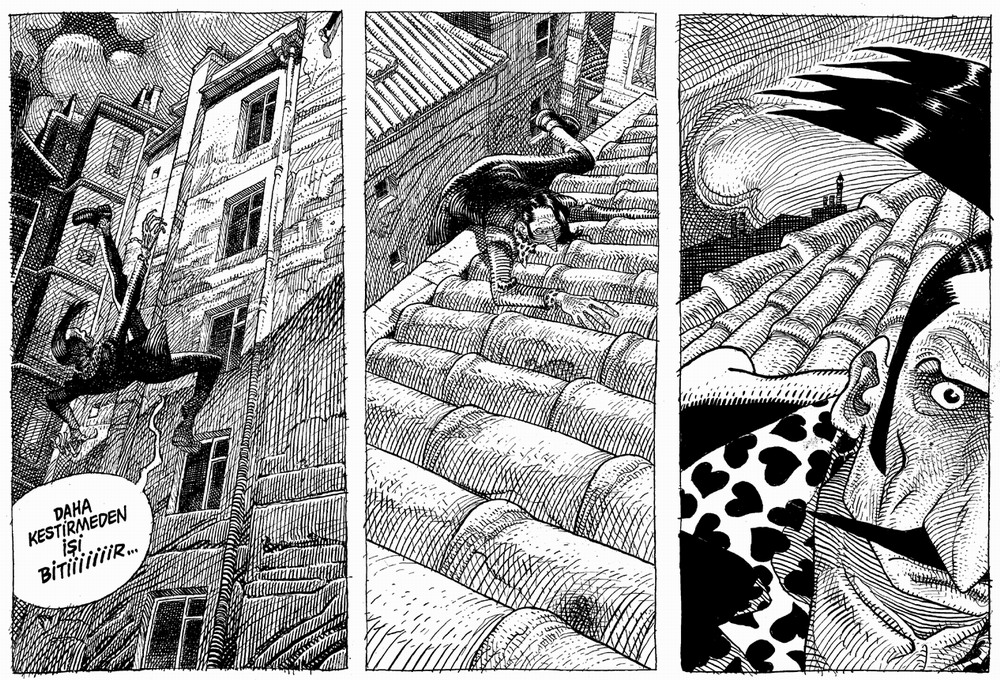

Nowadays comics in Turkey are styled on the narrative model of L-Manyak. It is thus important to understand the common aesthetic preferences at the base of the L-Manyak trend: as opposed to the very minimalistic approach cultivated by legendary editor Oğuz Aral, most editors now prefer drawings against a detail-loaded, photorealistic background and tiled page designs. Kötü Kedi Şerafettin (Şerafettin the Bad Cat) by Bülent Üstün showcases the punky past of the author and his aesthetic rebellion. In the L-Manyak “Martyrs” series by Memo Tembelçizer, the author recounts stories about his artist friends who find death in many different ways. Another subcultural story by influential artist Oky (Oktay Gençer), Cihangir’de Bi Ev (“A House in Cihangir”), revolves around a quarter of Istanbul, where Cihangir is shown as a bohemian space of the city, with a focus on adolescents’ sexual and emotional relations. Other typical examples of this period are Cengiz Üstün’s grotesque works that invert the logic of horror movies, like Kunteper Canavarı (The Kunteper Monster), and Gürcan Yurt’s Turkish take on Robinson Crusoe (Robinson Crusoe ve Cuma, or Robinson Crusoe and Friday). Other comics artists whose various works have recently made a splash are Bahadır Baruter, Kenan Yarar and Ersin Karabulut.

Finally it is of interest to expand on a few artists who have become prominent in the course of eighty years of local comics production. Suat Yalaz’s swashbuckling serial Karaoğlan (1962) and Turhan Selçuk’s formidable Turk in the last days of the Ottoman Empire, Abdülcanbaz (1957), were able to establish themselves on various platforms and keep up with the times, thus becoming classics in the Turkish comics scene. Sezgin Burak’s Tarkan is interesting because of its masterful originality and creative settings. Although Ratip Tahir Burak is considered by many to be a great painter who stands out for his artful drawing rather than his stories, he has become a model for the entire Gırgır generation. Oğuz Aral’s Utanmaz Adam has become a model as well for its successful scripts and well-conceived storylines. Engin Ergönültaş, born in 1951, deeply influenced the generations to come by creatively employing the original character of hınzır (originally meaning “swine,” “pork”; here in the sense of a boorish and unfeeling person) and through his literary visuality. Much of the production of today’s Turkish comics artists is deeply rooted in Ergönültaş’s influential artwork. With perhaps much more still to come.

Text by Levent Cantek, author of the book Türkiye’de Çizgi Roman, on the history and evolution of Turkish comics. Header image: Abdülcanbaz – The Istanbul Gentleman © Turhan Selçuk

Ed’s note: the magazine Gırgır, mentioned above, was closed down in February 2017 following the publication of a controversial cartoon. Those interested in finding out more may visit the CBLDF.