The post World War II period saw the prohibition of comics by the communist regime. By the end of the 1950s, some of the new laws brought in by the Yugoslav government had changed the situation concerning publishing. Private initiative became possible again, after being a bit restricted during a more rigid period after the WWII. In the late 1950s, comics again started “invading” various daily and weekly publications, from sports-themed, to children’s, even to military-themed. However, quality authors were few now and they could not meet the rising demands. This led to a military-themed magazine entitled Narodna armija (eng. National army) to issue a competition for comics and comic screenplays in early 1956. Among the peculiar publications were photo comics by Saša Bizetić, who created 23 stories in the years between 1955 and 1968.

The year 1957 would prove to be a significant one for comics in Serbia. It marked the publication of the 1st issues of Dečje novine, Kekec and Veseli Zabavnik, three magazines which conceptually resembled the pre-war Mika Miš. In terms of content, this was particularly evident in the case ofVeseli Zabavnik, the editor of which was Aleksandar J. Ivković, the man responsible for Mika Miš. Despite occasional censorship issues, Veseli Zabavnik would continue to be published and would reach issue #65 before being cancelled.

On the other hand, Kekec focused on content by Franco-Belgian authors and featured bande dessinée such as Raymond Macherot’s Chlorophylle, Franquin’s Modeste et Pompon, Peyo’sSchtroumpfs, Morris’s Lucky Luke and many more. Many of these comics were translated by a famous poet, writer and author of aphorisms Duško Radović. Kekec would reach unprecedented heights in popularity and print-runs of up to 300.000 copies (!) per issue.

The roots of the third of the 3 great above mentioned magazines – Dečje novine, were planted in an elementary school in a small town of Gornji Milanovac. In its early stages, the editorial team of Dečje novine was comprised of several enthusiast teachers. Little did they know that their modest magazine would go on to become one of the great publishing houses of Yugoslavia, lasting up to the early 1990s. The publishing house Dečje novine would, arguably, throughout the decades, with its numerous comic-based publications (Nikad robom, Kuriri, YU strip, Profil), do more for the comics scene of Yugoslavia than any other publisher.

Throughout this time, Politikin zabavnik survived, reprising some of the works by Đorđe Lobačev and Konstantin Kuznjecov, as well as offering opportunities to Ludvig Fišer, Božidar Veselinović and Novica Kruljević.

The 1960s brought new tendencies in the way comics were published. Specialised editions dedicated to certain genres of comics were established, such as Crtani romani (western-themed comics), Panorama (Franco-Belgian comics), Zenit (US comics, including Marvel), Miki (licensed Disney comics) and Nikad robom (historical and liberation comics) which launched the most famous domestic comics duo: Mirko and Slavko – little partisan couriers. The later publications of the duo’s adventures reached print-runs of up to 200.000 copies and spawned a motion picture released in 1973.

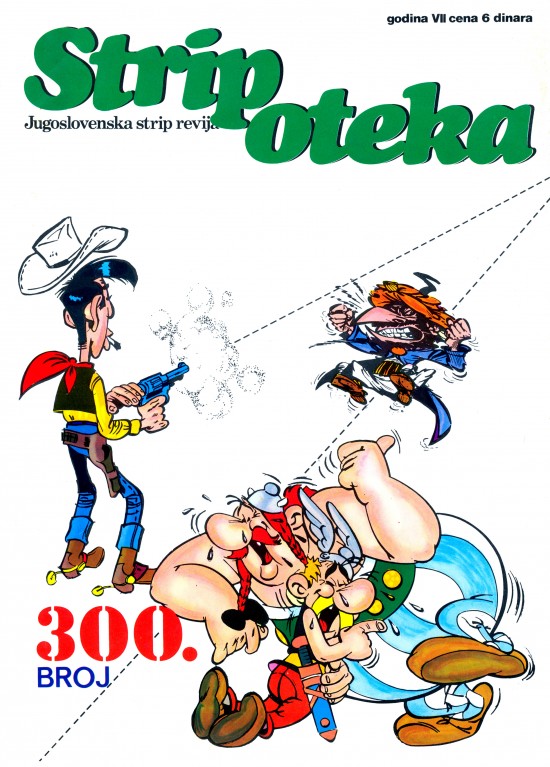

Particularly worth noting is that the above mentioned Panorama, after its cancellation, was succeeded by Stripoteka, which continues to be published to this day, making it the longest-running comics magazine in this part of Europe and the second longest-running in all of Europe (!). Throughout the decades, this magazine has withstood the test of time and continues to be the most influential comics journal in the entire region. The editorial duties of Stripoteka today are proudly run by the editorial team of Darkwood.

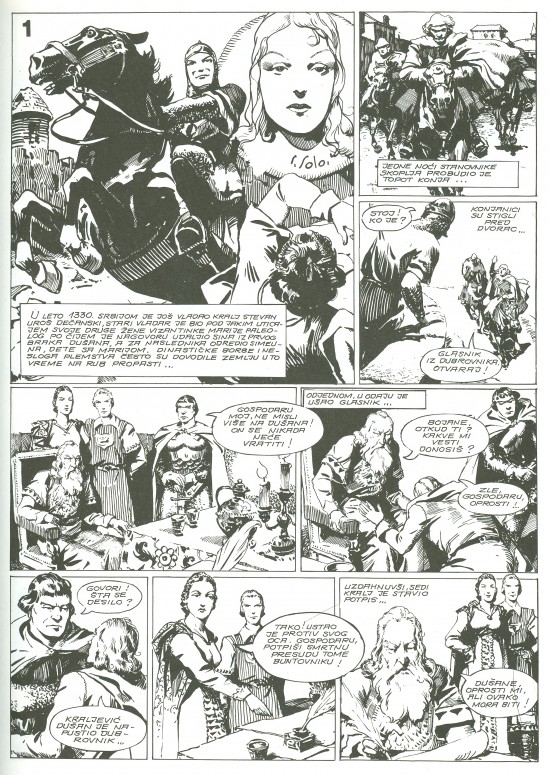

The most notable domestic authors of the 1950s and 1960s were Jovan Stojanović (alias John Radley), Aleksandar Krunić, Ludvig Fišer, Milorad Dobrić, Ivica Bednjanec, Živorad Atanacković, Ivo Kušanić, to name a few. The late 1960s saw the return of the incomparable Đorđe Lobačev with new creations such as Hajduk Veljko and Čuvaj se senjske ruke.

In the year 1969, one of the most popular domestic comic characters, Dikan was created. This humouristic comic, created by Ninoslav Šibalić and Lazar Sredanović, followed the adventures of Dikan and Vukoje at the times of Ancient Slavs.

Along with the renaissance of comics in Yugoslavia, the early 1970s were also marked by a new, restrictive political line in the country, which led to criticism of the comics form and even administrational measures through extra taxes added by a special comission against what was called “kitsch literature”. Some magazines and editions were forced to stop publishing, but the form recovered in years to come.

The rise in popularity of comics in the late 1970s and 1980s became evident once again with editions such as YU Strip (Dečje novine), Lunov Magnus Strip and Zlatna Serija (both published by Dnevnik), Asteriksov Zabavnik (Forum) and Biser Strip (Dečje Novine). Albeit the latter ones were mainly licensed publications of popular Italian and Franco-Belgian comics series, YU Stripprovided (much like Mika Miš decades ago) an invaluable proving ground and launching pad for a new generation of comics artists, such as Bane Kerac, Toza Obradović, Sibin Slavković and Branko Plavšić. Their licensed editions of YU Tarzan were published in Scandinavian countries. The popularity of comics in the 1980s was reaching great heights once again.

However, the hardship of the 1990s caused another sudden stop in everything. Until the mid 2000s, the publishing efforts in Serbia were sporadic and very few. Yet, even in the years of turmoil, domestic artists were doing well in establishing themselves worldwide. Artists such as Darko Perović, Aleksa Gajić, Stevan Subić, Dejan Nenadov, Bane Kerac, Dražen Kovačević, Dragan De Lazare, Zoran Janjetov, Gradimir Smuđa, R. M. Guera have all become well respected artists outside the borders of Serbia and the region.

Meanwhile, in Serbia, recent years and efforts by several new, enthusiastic publishing houses have reignited the comics scene. In the past couple of years, around 300 titles of all schools of the Ninth Art (Franco-Belgian bande dessinée, Italian fumetto, Japanese manga, US graphic novels) are being published annually, almost the third of which by Darkwood publishing house.

By Dejan Savić

In Memoriam: Zdravko Zupan