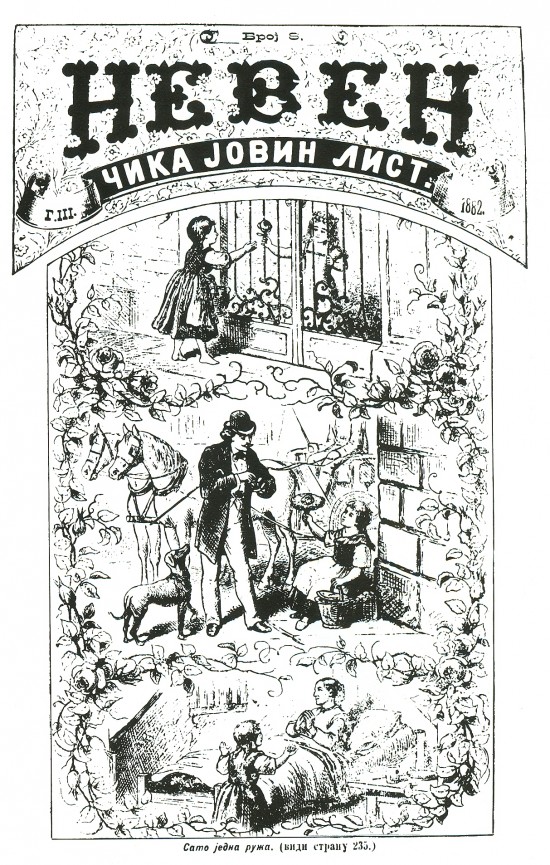

The earliest beginnings of comics (or perhaps best referred to as “proto-comics”) in Serbia can be found in Jovan Jovanović’s satirical magazines Zmaj, published between 1864 and 1871 and Jazavac published in 1872. Yet, until the appearance of Neven magazine, these and other early forms of comics made merely occasional appearances on the pages of humoristic magazines, almost always with the purpose of satirical depiction of current political and social events. The official “birth” of comics in Serbia may be attributed to the first issue of Neven, published in January of 1880 in Novi Sad. Its founder and editor was the aforementioned Jovan Jovanović Zmaj. Albeit intended as a children’s magazine, it quickly gained favour among adults, as well. It would go on to be published regularly until 1890 and again between 1898 and 1908. Although many of the illustrations were works of foreign (mainly German) authors, some of them were drawn by Jovan Jovanović himself, with contributions by one of the greatest Serbian painters Uroš Predić. The jests featured in Neven were of humourous or educational nature, typical for their rhyming verses below the illustrations (balloons, as a method of narration, were not established yet) and no serialised characters. Zmaj’s “proto-comics” preceded even the appearance of the famous Yellow Kid and paved the way for the future Serbian/Yugoslavian comic scene.

The first serialised comic book characters in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes were Maks and Maksić, two mischievous boys created by Sergije Mironović Golovčenko. First of these gag-strips was published on April 4th, 1925 in a magazine called Kopriva. Maks and Maksić were extremely popular and the four books which collected the mishaps of the duo were sold out in record time. The readership’s hunger for comics was apparent.

As a result, Serbian newspapers began introducing supplements for children, which featured jests and comic-strips. First such addition was introduced by the famous daily newspaper Politika on January 16h 1930, entitled Politika za decu (eng. Politika for children). Soon to follow were journals Vreme (eng: Time) with its supplement Dečje vreme (eng. Children’s Time) and Novosti(eng: News) with Novosti za decu (eng. News for children). Worth noting is issue #31 of Politika for children and the episode entitled Brash burglar and brave Perica which featured the first ever use in Serbian comics of the most typical means of textual communication – balloons. Later issues of Politika for children would feature syndicated Disney’s comic-strips. Disney’s characters would become a sort of trademark for Politika’s later publications, such as Politikin zabavnik (Politika’s entertainment magazine), first published in 1939, which remains the most important magazine in the history of Balkan pop-culture. The magazine continues to be published to this day.

However, credits for the first publication of Disney’s characters to the domestic audience go to an illustrated children’s magazine called Veseli Četvrtak (Happy Thursday). Such a magazine, at a time when comics as a medium were just gaining popularity in newspapers, represented a significant novelty. Published in Belgrade in 1932-1933, its 16-page content was comprised mainly of comics, short stories, songs and riddles.

Serbian comicbook historians are unanimous in their claims that the decisive stimulus for the development of the Ninth art in Serbia was the appearance of Secret-agent X-9 by Alex Raymond and Dashiell Hammett on the pages of the Belgrade newspaper Politika on October 21st 1934. Announced as “a novel you can read two minutes per day” as well as “having a cinema in your own home”, the comic garnered considerable readership practically overnight. The incredible success of this comic caught the eye of and inspired domestic authors, such as Vlastimir Vlasta Belkić, Aleksandar Ranhner and Đorđe Lobačev. This would lead to the publication of a number of syndicated comics on the pages of Politika and Vreme, such as Tim Taylor and Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies. Unlike Politika and Vreme, illustrated magazinesNedelja and Panorama put their trust into the hands of domestic authors, many of whom were of Russian origin.

Namely, after the October Revolution, a number of “Whites”, Russians that represented the political contra-distinction to the Red Army, fled from Russia and found their home in the then Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Among them were a number of artists who would go on to become the most important Serbian comic artists of the 1930s and form the so-calledBelgrade Circle: Đorđe Lobačev, Sergej Solovjev, Konstantin Kuznjecov, Nikola Navojev, Ivan Šenšin and Aleksije Ranhner. Other notable artists of that time include Đuka Janković, Sebastijan Lehner, Moma Marković, Marijan Ebner and Đorđe Mali. The most notable writers were Branko Vidić and Svetislav B. Lazić.

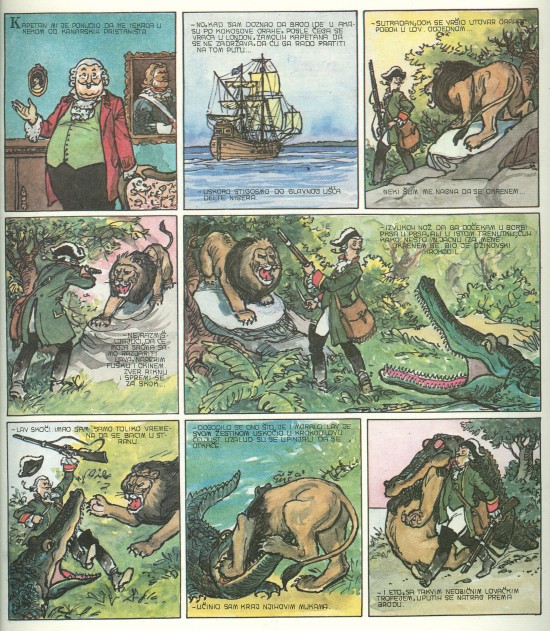

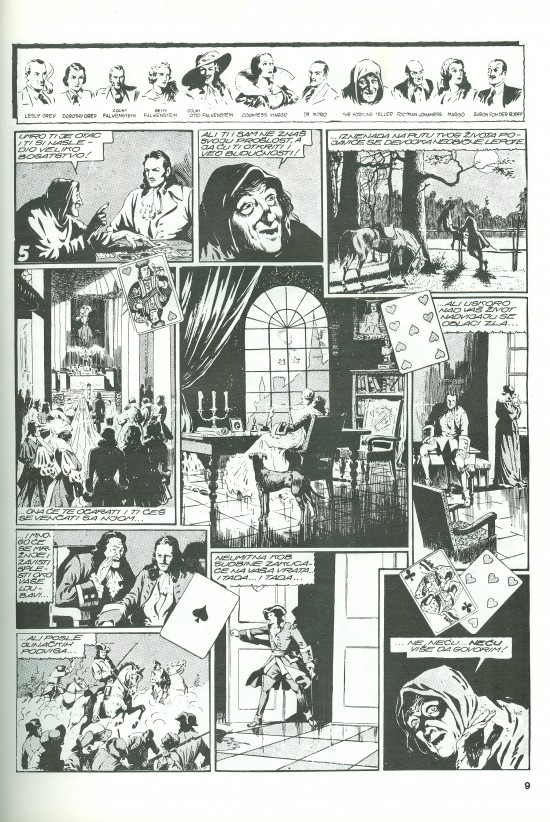

Amazed at the quickness of the rise in popularity of comics, publishers started considering different means of presenting them to the audience. This led to the establishment of magazines such as Strip (eng. Comic), which was largely influenced by Italian Topolino, and Crtani film (eng. Cartoon), both in 1935. The influence of not only US comics, but of Italian and French schools of the Ninth art were becoming all the more evident. At the same time, domestic authors were coming to their own and their works on the pages of these magazines received all the more prominent roles. Shortly before the cancellation of Strip and Crtani Film, new forces in the form ofMikijeve novine (eng. Mickey’s journal) influenced by French Le Journal de Mickey, and Mika Mišwere established, both in 1936. While Mikijeve novine primarily focused on syndicating Disney’s comics, Mika Miš served as proving ground for many of the above mentioned artists of the Belgrade Circle, giving a number of them their first opportunities to hone their craft. And did it ever pay off. In short period, thanks to authors like Lobačev, Navojev, Solovjev, Kuznjecov, Šenšin… the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was quickly becoming one of the epicenters of European comics in the pre-World War II period. Many of the works of Belgrade authors were being published in France, despite the dominance of US authors in Europe at the time.

Mid and late 1930s were, without a doubt, the golden age of domestic comics, with insatiable readership craving more. This led to strong, healthy competition for the till then undisputed Mika Miš, in the form of Mikijevo carstvo (Mickey’s Kingdom) and the already mentioned Politikin Zabavnik. This was creation period of some of the legendary series such as Zigomar and Hrabri vojnik Švejk (an adaptation of Jaroslav Hašek’s famous novel), among many others.

Issue #504 of Mika Miš was published on April 4th 1941, two days prior to bombing of Belgrade. World War II would put the creative wave of momentum to a halt. In just six years (1935-1941) over 20 different comic magazines and over 15.000 pages of comics were published, over 5.000 of which were created by domestic authors.

.