Jijé, Hergé, Rob-Vel, and the portrayal of Jews

Was publisher Dupuis trying to protect Jijé’s image by excluding two of the star artist’s stories written in 1939 and 1940 from publication in a full-length volume? That’s the position of Philippe Mouvet, a key source for The True Story of Spirou (La Véritable Histoire de Spirou), a book covering the early years of the magazine.

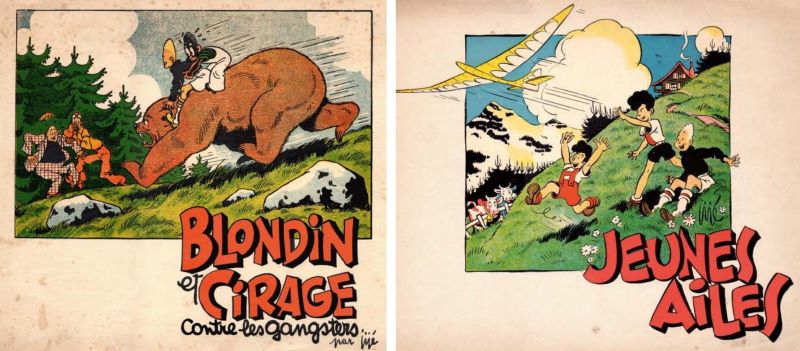

Jijé targets the Jewish community in both stories, harnessing the prejudices that were part of mainstream thought at the time. This turn of events is uncomfortable, to say the least. And even more astonishing, considering the fact that Jijé had created the series in question in response to Hergé’s colonialist leanings. “Jijé for sure put whites and blacks on an equal footing in Blondin & Cirage. A far cry from Hergé’s paternalistic output in the early thirties that was being published in the right-wing Catholic newspaper, Le Petit Vingtième,” Mouvet adds. It’s clear enough if you look at the stories, Mouvet says: Blondin, a light-skinned blond boy, and his black step-brother, Cirage, are equally smart. Mouvet points out that Cirage may even be a little sharper than his blond counterpart. So it’s surprising, to say the least, when Cirage simply disappears from the series in 1940.

The duo made their first appearance in Blondin and Cirage in America, the first story published in 1939 in Petits Belges. The two go looking for their father, who had left to seek his fortune in the States. The next story, published in 1940, finds them still in the US. They are together up until the final pages, when Cirage is offered a part in a movie and swiftly takes his leave. He’s nowhere to be seen in the third story, Jeunes Ailes (Young Wings) (1941) and we realize the series has changed its name. Instead of Blondin and Cirage, it’s now Jeunes Ailes. The story picks up with Blondin traveling to Switzerland with his father at the invitation of a colleague who is also an engineer. Along with the colleague’s sons, Blondin enters a model airplane competition. The plot was heavily influenced by the old-school spirit of Spirou Aviation clubs, focusing as it did on rivalry and competition between the young contestants. There’s no reference whatsoever to Cirage… “Did our little black friend disappear because of pressure on Jijé by the editor of Le Croisé who perhaps feared German censorship?” Mouvet muses. “Or was it a precautionary measure taken by Jijé himself? No one can say for sure.” But one thing was clear: Jijé, the progressive who had been the first to include a black protagonist in his comics, saw his image well and truly shattered.

But there’s something more insidious in Jijé’s work. While Blondin and Cirage had very much been a stand against Hergé’s conservative views, the artist used other troubling caricatures, like the one of the evil Jewish business magnate. Mouvet notes this was not the case in Jijé’s early stories. Not in Jojo, published in Le Croisé between 1936 and 1939, nor in Freddy Fred: Le mystère de la clef hindoue in 1939, published in Spirou and later on in Le Croisé. The caricature in fact only emerges in later stories written for Spirou, starting with Trinet et Trinette dans l’Himalaya (1939), in which the titular protagonists set off to climb a Tibetan mountain with their uncle Jacques Martel and the explorer-mountaineer Moulineau. There is a prize offered by a wealthy businessman for whoever is the first to reach the top.

Our heroes are up against a rival expedition looking to scoop the prize, led by the explorer Smit. “Smit is anonymously supported by someone that we later find out is a wealthy Jew with Machiavellian plans, who is using his money to sabotage the other teams,” explains Mouvet. “The character first appears in the series on December 14, 1939, so before the start of the war. It makes you think: Why would Jijé characterize his archetypical villain as a rich, sneaky, unscrupulous Jew? Especially as this is the character’s sole function in the story. The explanation might have something to do with how Catholic Jijé had been. In his younger days, as a student at the Maredsous monastery, he had probably absorbed the stereotypes of Jewish people that circulated in 1930s Catholic society. In creating a slick, unscrupulous character who would use wealth to achieve dishonest ends, he unsurprisingly went with a Jew. This probably says more about the mentality and ideas that had currency in Catholic circles at the time, than about the opinions of Jijé himself. At least, that’s what I hope…”

In May 1940, Germany invaded Belgium, and Rob-Vel’s pages of Spirou sent from France could no longer reach their destination at Dupuis. Jijé jumped into action. Wrapping up Rob-Vel’s running story at a fevered pace, he embarked on the first Spirou story that would be entirely his own. In the magazine’s forty-fifth issue, the plot revolved around the launch of Spirou’s career as a movie star. The protagonist is hired by Mr. Boss, who runs the BB Cinema film studio, but is thwarted at every turn by Isaac Godsak, the owner of a rival company. The rich businessman character is quite clearly a Jew. When Spirou foils him, he takes his revenge. “Again it’s not clear why Jijé used the short story to include a rich devious Jew. For sure, the story came out under German occupation and censorship, and Dupuis certainly allowed it. But we’re not sure if it was the result of mainstream prejudices or Jijé’s personal beliefs.”

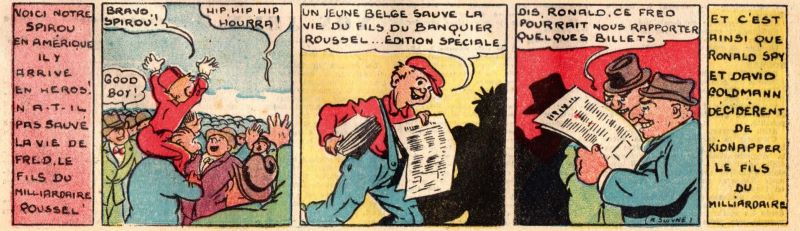

But to blame Jijé alone would be a mistake. Rob-Vel, for example, the creator of the redheaded bellboy and the magazine’s figurehead, also caricatured the Jews. In Spirou: Vedette de cinéma, Rob-Vel introduces an archetypal villain named David Goldman. The episode—published in the sixth issue of Spirou on February 8, 1940, before the start of the war—features a plotline in which Goldman and his friend Ronald Spy kidnap little Fred. Fred is the son of a Belgian billionaire, who had been saved from drowning by Spirou. “The Jewish villain predated Jijé’s takeover of the series, and in any case, didn’t make any more appearances after that issue,” said Mouvet. “Regardless, when issue 6 of Spirou came out, Jijé had already written 26 pages of Trinet et Trinette, including those that included the Jewish villain. So while Jijé was the first to use the stereotype in his own series, Rob-Vel had been ahead of him in writing for Spirou. In any case, Jijé wasn’t motivated to introduce yet another Jewish villain.” Mouvet confirms: “This is not the real point though. Despite those characters, Rob-Vel’s story stayed on the magazine’s front page for 25 weeks. Fourteen before the war started, and eleven from the magazine’s reappearance on August 22, 1940.” He concludes: “It seems that, before the war, no one at Dupuis was getting particularly upset by these nauseating Jewish clichés, assuming they knew about them.”

Tintin, Blumenstein and Nazi Smurfs

The abovementioned examples of anti-Semitism didn’t stir up much controversy, perhaps because they were only published in magazine format, and were thus allowed to fade away in the annals of history. What did eventually tarnish Hergé’s reputation as the master of Belgian comics turned out to be a supporting character in The Shooting Star (L’Étoile mystérieuse). While Tintin in the Congo had gone some way in proving that Hergé looked down on black people, it was The Shooting Star that brought the critics out in full force, branding him both an antisemite, as well as anti-American.

The story was published in late 1941 in the so-called “Le Soir Volé” (The Stolen Le Soir) as the newspaper came to be known under the German occupiers. Hergé introduces to the story a rich, conniving character called Blumenstein, a businessman who is clearly Jewish. Blumenstein does his best to ruin Tintin’s scientific expedition. That said, by the time the story was set to appear in a full-length volume, the character had lost the name Blumenstein. It seems Hergé got wind of critical reactions from some corners of society, and renamed the character Bohlwinkel instead, a term often used in Brussels to denote a candy store. The character also lost his Jewish-American traits, becoming instead a banker from the fictional Sao Rico. So it was rather unfortunate when it later emerged that Bohlwinkel is in fact also a Jewish name. Too late, as Hergé had used the name change as a get-out-of-jail-free card. Interestingly, when the full picture emerged, Hergé made no moves to change the name again.

Across Belgian comic book history, Tintin wasn’t the only one to be called out for antisemitism. In 2011, it was Peyo’s Smurfs who came under fire. In his book Le Petit Livre Bleu (The Little Blue Book), the French author Antoine Bueno presents a “sociological study” of the Smurfs, concluding that they were “authoritarian, racist and chauvinistic.” To be fair, their enemies are the black Smurfs, they live in an authoritarian and patriarchal society, and Gargamel, their nemesis, has typically Jewish features. Bueno concluded that the society in which Peyo’s little blue creatures live is nothing short of “the manifestation of an authoritarian utopia, anchored in Stalinism and Nazism.” Papa Smurf himself puts out some pretty strong paternalistic vibes.

“It’s a real shame that my husband is no longer here to defend himself,” said Nine Culliford, Peyo’s widow, in response. “The accusations are harsh and unfair, especially given that my husband never took any political or religious stance.” Véronique, Peyo’s daughter and head of IMPS, the Genval-based company that manages the Smurfs, maintains that the book got it all wrong. “This man didn’t even look for evidence to back up his accusations. He says Gargamel seems Jewish and that the name of the cat Azrael but a distortion of ‘Israel.’ By making them the two villains of the story, he seems to believe this made my father hostile to Jews. What a load of crap! You want the real story? My father often collaborated on his storylines with Yvan Delporte, who was married to a Jewish woman. It was she who came up with the name Azrael. It was just an inside joke.” According to Nine Culliford, Peyo even asked Yvan Delporte if his wife was all right with it. “He said it was no problem. Sadly, things that were not an issue at all a few decades ago seem to have now become controversial.”

Excerpt from La Belgique dessinée, by Geert De Weyer (Ballon Media, 2015).

Translated by Storyline Creatives.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily represent the views of Europe Comics.