by Laurent Mélikian

European bookstores make it abundantly clear that the graphic novel has become a mainstream phenomenon. Across Europe, bookstores once reluctant to stock comics have now opened up their doors to readers increasingly interested in illustrated stories that tackle some of the most significant issues of our time. In Spain and Italy in particular, this trend is well entrenched. In the final part of our journey through Europe, we will linger along the shores of the Mediterranean.

Paco Roca: From tebeos to realism

In Spain, tebeos (“comics”) have a fan base that spans generations. But, as elsewhere, the presence of comics on Spanish newsstands has been in decline since the 1980s. Fifty-year-old Paco Roca is one of the authors who had to make his transition into bookstores, following a career in magazines. “I wanted to become an author after reading popular comics from Bruguera [ed’s note: a publishing house based in Barcelona], then Asterix, Tintin, and the superhero comics… I was taken by the autobiographical series Paracuellos [a story about Franco-era orphanages, published by French monthly Fluide Glacial] by the Spanish author Carlos Giménez. He made me realize that we can tell beautiful stories without centering them on adventurers.”

Roca has been acclaimed by a wide audience since 2007, when he released Arrugas (Astiberri; Wrinkles, Fantagraphics), a graphic novel dealing with the subject of Alzheimer’s (adapted into an animated feature film a few years later). The book also marked a turn as Roca began to base his work on real events. With El Angel de la Retirada he tackled the Spanish Civil War, followed by the Second World War with La Nueve (Twists of Fate, Fantagraphics), and familial accounts with La Casa (Astiberri; The House, Fantagraphics). All topics that in one way or another cross borders: “I write about what is close to me, my life, my knowledge. And I belong to a European culture. Naturally, I think of Spanish or European readers when I work. But I can be read on other continents too, because I believe that the graphic novel has made comics international. While superheroes and Franco-Belgian albums are published all over the world, graphic novels on the whole have been considered as being primarily targeted at an American readership, just as the Franco-Belgian works are aimed first and foremost at French-speaking readers in Europe.”

Jesús Alonso Iglesias: Beyond Europe

“The graphic novel has undoubtedly enabled European comics to become international,” agrees Jesús Alonso Iglesias. Like many Spanish artists, he found his professional success in foreign markets. On the one hand, he’s made comics for French-language publishers, and on the other, he’s worked as a story-boarder and character designer on American animation projects. He was also a contributor to the astonishing Spider-Man Multiverse. Following PDM, his debut graphic novel written by Swiss editor Pierre Paquet, he illustrated El Fantasma de Gaudi (Dibbuks; Ghost of Gaudi, Europe Comics/Lion Forge) alongside scriptwriter El Torres, offering up a Barcelona-based thriller in which the basilica of the Sagrada Família and its architect play a key role. The book was selected for both the 2018 San Diego Eisner Awards and the New York Harvey Awards. “The comic industry values us as an alternative to superheroes,” Alonso Iglesias says with pride. Published in countries such as former Yugoslavia, Germany, and Portugal, the artist is an avid European festival-goer and remains curious about everything: “At every festival, I find new comics that could influence mine, works even from younger authors than myself…”

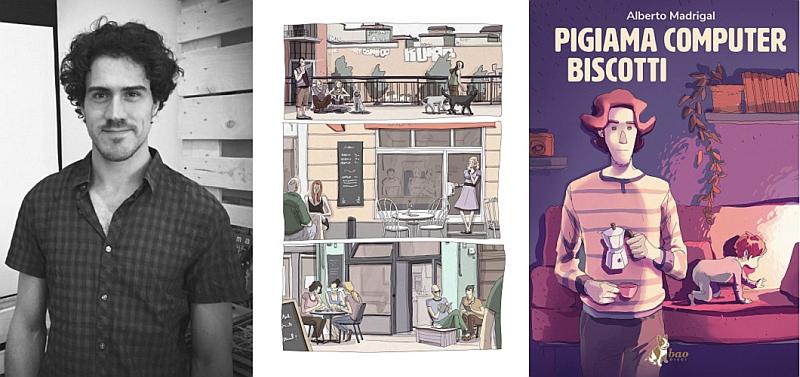

Alberto Madrigal: Ich bin ein Berliner

They say it can sometimes be difficult to succeed in one’s own country. Never has this been more true than with Alberto Madrigal, born in 1983 in Spain: “I spent a long time looking for work as an artist with French publishers, with no success. Then, for personal reasons, I moved to Berlin. There I started drawing my first autobiographical book, and since I was discussing it with some Italian friends, I started writing it in Italian and offered it to an Italian publisher,” he recalls. “And here I am, an accidental Italian author!” Un lavoro vero (A Real Job, Europe Comics) was published in Milan by Bao Publishing in 2014. “As Italian isn’t my mother tongue, I kept the language simple, and that in turn makes my work easier to follow.” Alberto later saw his books translated into Spanish, and in France, he illustrated Berlin 2.0 (published by Futuropolis) based on a script by Mathilde Ramadier, another Berlin transplant. Two Italian graphic novels followed, Va tutto bene in 2015 and Pigiama Computer Biscotti this year. “I now understand the Italian comics market better than ours in Spain. Thanks to Gipi and Zerocalcare, there has been great progress over the past five years. Graphic novels are thriving in bookstores and more people are reading them. I was recently at the Turin International Book Fair for the release of Pigiama Computer Biscotti, and people came especially for the launch. It used to be that we were surprised to see even one comic book writer at a book fair…”

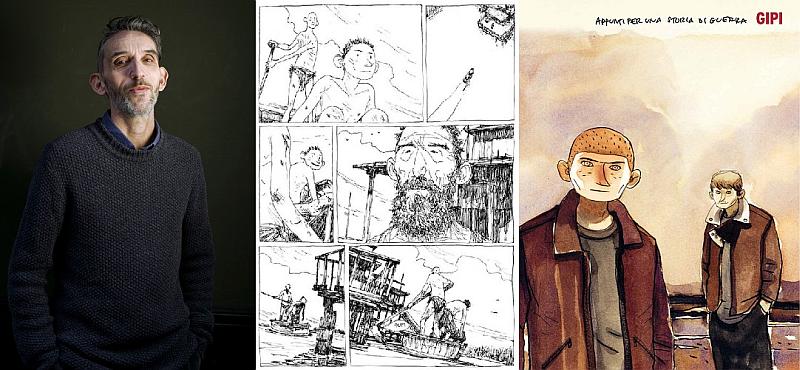

Gipi: Traces of war

Fifteen years ago, Gipi burst onto the scene with his debut work Appunti per una storia di guerra (Coconino; Notes for a War Story, First Second), displaying his characteristic style, somewhat fragile in look, but elegant and dynamic. It tells the story of three teenagers who live in a war-torn Italy, still reeling from conflict with former Yugoslavia. European readers were awestruck by Gipi’s disturbing artwork. Appunti per una storia di guerra was recognized as Best Album at the Angoulême Festival in 2006. “I’m European, so my voice is naturally European,” says Gipi. “But these days, when I think of Europe, fear influences my reasoning. A fear that Europe will once again fall apart and we will find ourselves in conflict as we did up until 1945. I’m quite certain this fear bleeds through and comes across in my work. “

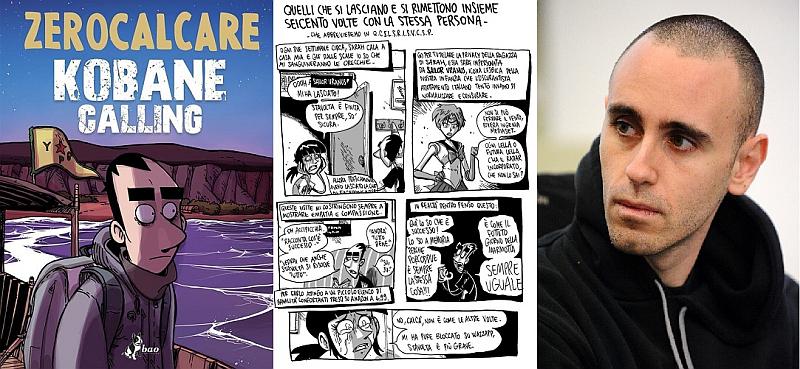

Zerocalcare: From online presence to print

“The status of comics in Italy changed once Gipi published his first few books,” explains Zerocalcare. “We began accepting comics as a language, as opposed to a genre, like Disney magazines or the monthly adventure stories from Bonelli.” With several autobiographical chronicles in which he humorously conveys his leftist political sensibilities, Zerocalcare, born in Rome in 1983, has become a publishing phenomenon. His new releases sell over 100,000 copies. About a decade ago, he started publishing his work as a blog. “Autobiographies were almost non-existent in Italian comics at the time,” he says, “and since, unlike other authors, I come from a highly politicized background, and I saw the Italian intellectual class shrinking, I decided to take on different subjects. Which ended up leading to a media phenomenon…”

Kobane Calling stands out among Zerocalcare’s titles. The author leaves his Roman neighborhood of Rebibbia to spend time with Kurdish fighters in the Syrian war zone. When it was adapted in French by Cambourakis in 2016, the book had a huge impact in France. Regardless, Zerocalcare doesn’t see himself as a prominent author throughout Europe: “Italy is the only country where my books do well. Kobane Calling did well in the French market, but the same can’t be said for my other books that have more to do with Italian society.” Still, his mother is French (from Nice) and he experiences the effects of having more than one nationality: “There are a range of influences in my work—Gipi, Boulet, Dragon Ball… I’ve created a kind of Frankenstein’s monster… In 2007, I was blown away twice, first by Ma vie mal dessinée by Gipi and then by French author Manu Larcenet’s Le combat ordinaire (Dargaud; Ordinary Victories, Europe Comics). These authors had vividly captured intense and moving snippets of life, each in his unique way. I don’t know if graphic novels are inherently European, but in the end, I feel more influenced by European authors than American ones, I couldn’t say exactly why.”

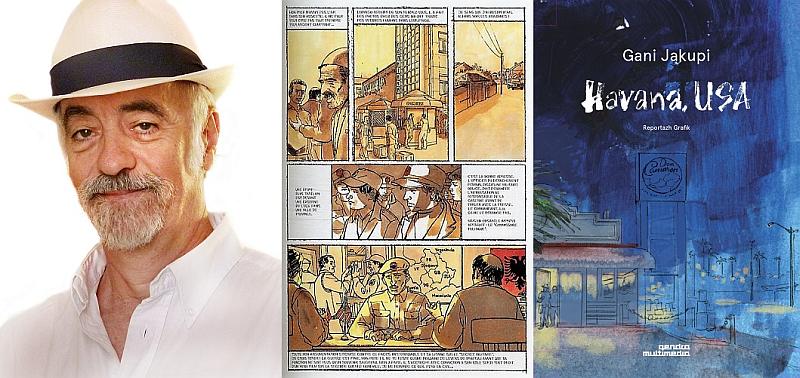

Gani Jakupi: Diverse voices

Where else could we end our journey but with Gani Jakupi? Born in Yugoslavia in 1953, a jazz musician, graphic novelist, journalist, novelist, and photographer, Jakupi lived in Paris for years before settling in Barcelona, where he explored his Kosovar identity following the fall of the Yugoslavian federation. “I was brought up reading Serbian magazines from the 1970s,” says Jakupi. “The authors came from all over former Yugoslavia and beyond. We were limited by Tito’s dictatorship, but nevertheless had access to a wide-ranging global culture that forged my artistic identity. My move to France in the late 1970s meant I had to adapt, and my current success as an author in the French-speaking world is due to this effort of adaptation.”

Published in English, German, Spanish and many Balkan languages, Jakupi recently put the finishing touches on his latest work, El Comandante Yankee (The Yankee Comandante, Europe Comics), a graphic novel about the Cuban Revolution, published in French by Dupuis. He has also just organized the first comics festival in Pristina, Kosovo. “In the Balkans, comics are now used to facilitate national narratives,” he says. “The graphic novel, a visual medium that remains little known, can in fact open new doors. As for me, my main goal is to have an impact on people. When I gather Finnish, Catalan, or British authors in Pristina, it might seem like they’ve come from outer space… But whereas a poet is inspired and nourished by his own language, these artists can express themselves in eye-catching drawings that draw inspiration from many places. Their differences are what allow us to build a rich culture and create something unique. It is here that Europe offers its greatest value.”

Published in collaboration with ActuaBD.com (article in French here). Text by Laurent Mélikian, journalist and international comics specialist.

Header image: The Yankee Comandante © Jakupi / Dupuis