The legendary Floc’h speaks with comics journalist Aug Stone for a rare English-language article about his life and work.

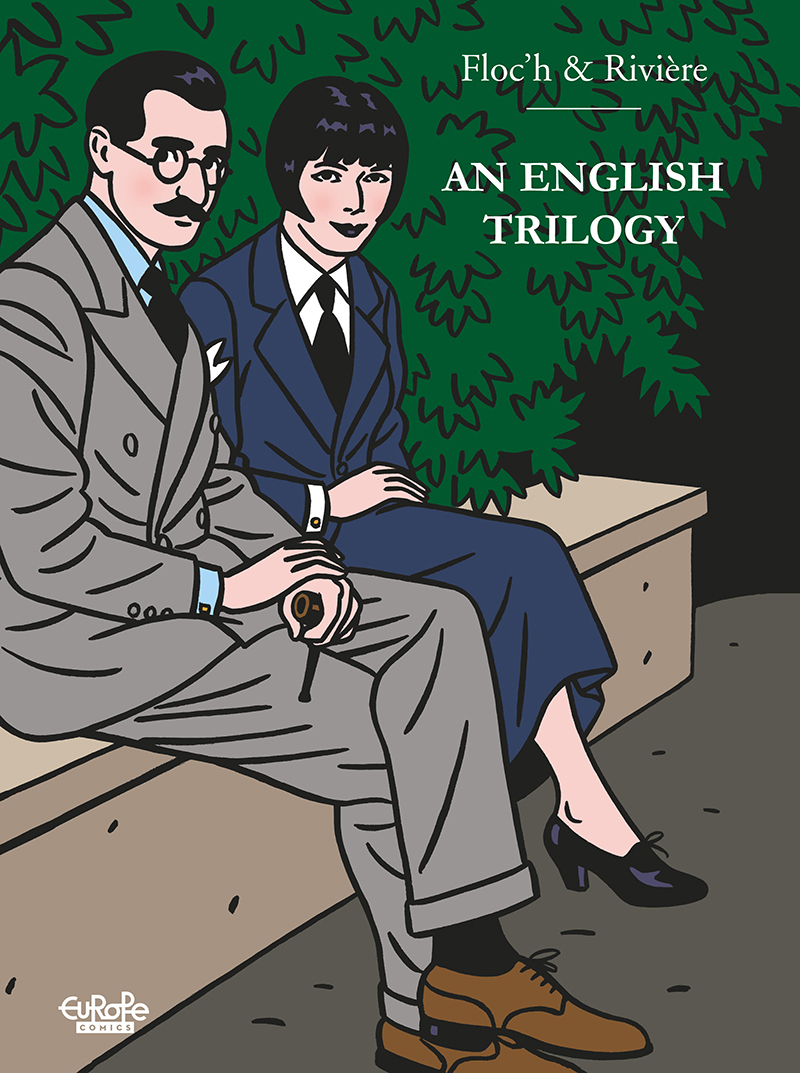

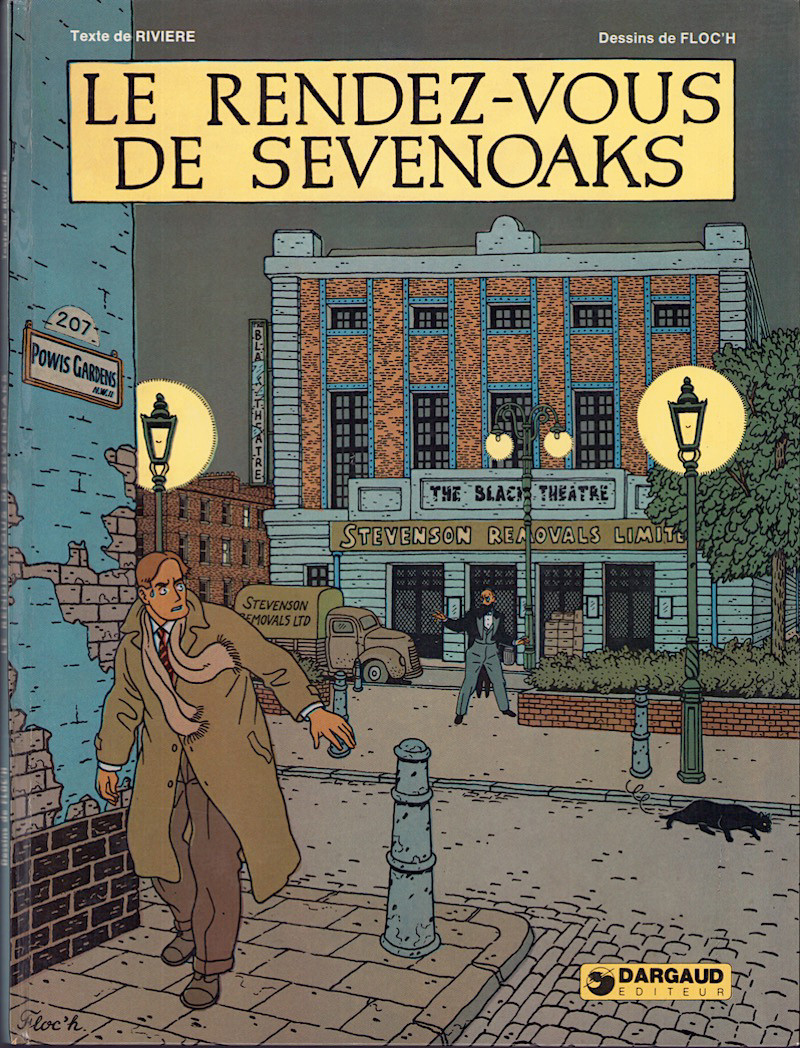

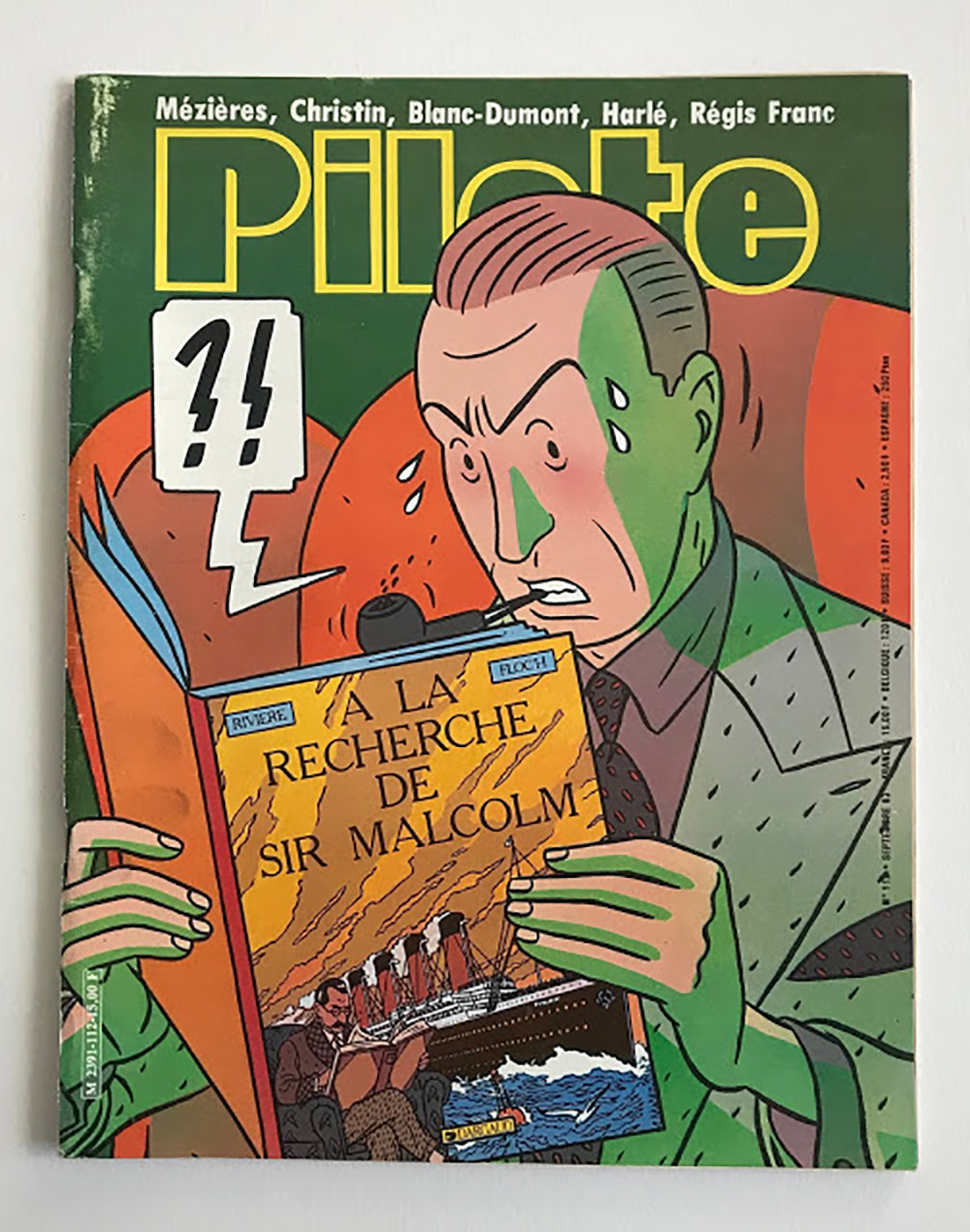

Floc’h is speaking to me from the south of France, having left his lifelong home of Paris two years ago, much to the surprise of his friends. We are discussing his & François Rivière’s Une Trilogie Anglaise (An English Trilogy) – collecting the books Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks (‘Rendezvous in Sevenoaks’, 1977), Le Dossier Harding (‘The Harding Case’, 1980), and À la recherche de Sir Malcolm (‘In Search of Sir Malcolm’, 1984) – translated into English for the first time and published by Europe Comics this month. Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks introduced the world to the artist known solely as Floc’h, the apostrophe between its C & H purely a stylistic choice, and a lot has changed over the course of his career.

“I’m 67 now. I’m in very good shape. I’m not feeling old, and I regret it. I would like to have grey hair because the worst thing in life is to be…(he considers his words) not a nobody, but a young guy. A brat. The Ramones were so right, the only way to cure them is to get the baseball bat (laughs). Because it’s embarrassing not to be grown up. I was in such a hurry to do things. I began Sevenoaks when I was 21. I was only 21 and every day I was saying to myself, ‘you are late, you are not quick enough’ (laughs). I was yelling at myself, but looking back I see that this was good in a way. Not my drawing, but my artistic expectations were good.” When I suggest he means ‘ambition’, he disagrees, clarifying “without art, life is not worth living. So I really needed to have artistic expectations, you see?”

“At that time, the very beginning of the 70s, we had three absolute needs to stay alive. The first one, let’s be honest, was girls. The second one was let’s say love, finding love. And the third was art. Books, etc. It was a time when you could do a lot of new things. And for me, there was also England. I’m the kind of guy that says ‘life without England is not worth living’. Especially at that time, it was my oxygen. I needed that so much. It’s like Lou Reed’s song, ‘Rock’n’Roll’. Voilà. Rock’n’roll saved my life. But I think that books saved my life much more than rock n roll.”

Floc’h is recognized as one of the masters of the ligne claire (‘clear line’) school of drawing, pioneered by Hergé and E.P. Jacobs. These influences, along with that of Jacques Tardi whose own take on ligne claire was gaining popularity in the 70’s, would inspire Floc’h’s first published books as he developed his style into what we see today. “Except for Joost Swarte and myself, at that time nobody was in love with Hergé, because nobody was in love with the past. So I said ‘I will do what is my culture, but I will do it the way I want to do it’. The idea was not at all to be like Hergé or Jacobs, because we were no longer in that beautiful time of innocence. This was the counterculture. We were a generation who were discovering irony. A lot of movies at the time were playing with the idea of movies. Sevenoaks, even if I was drawing very badly then, was the first comic to feature a story within a story. I was bringing something to comics. I wanted to kill any idea of adventure. Adventure, I don’t give a damn (laughs). What I wanted to do were stories around a cup of tea. In a way, we had all these influences who were giving us the opportunity to be much more playful.”

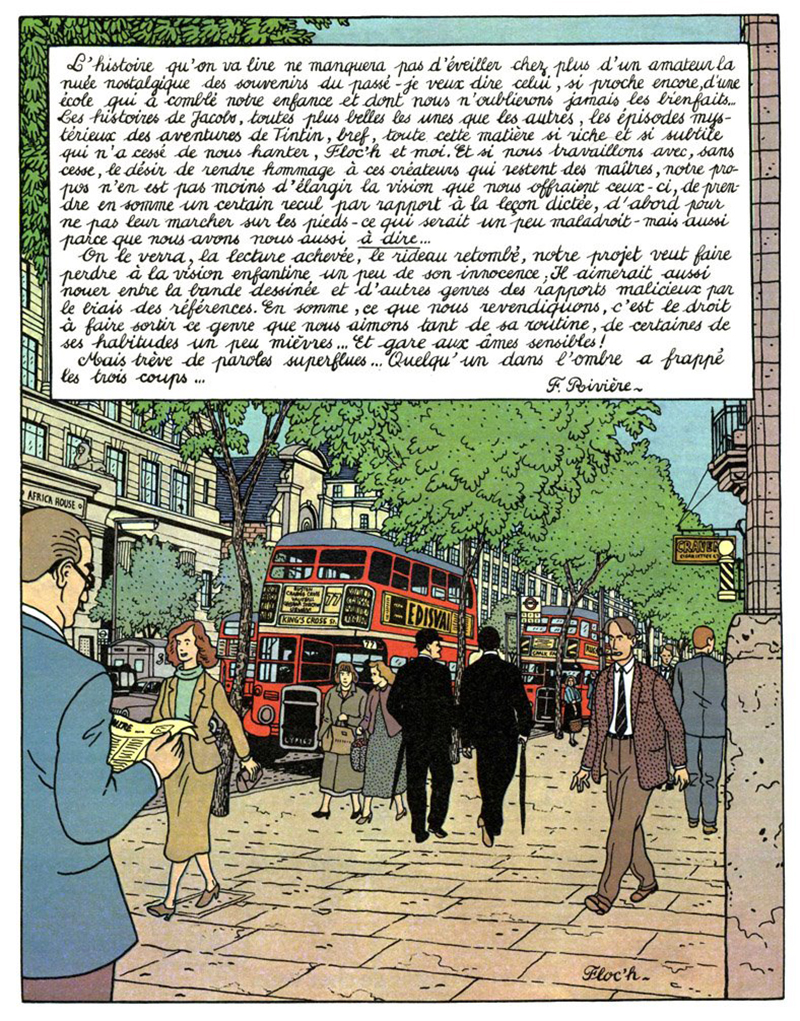

Despite Floc’h’s comments on his nascent illustration work at the time, Sevenoaks is notable for what he and Rivière were attempting to do, which was nothing short of revolutionizing the world of comics. Indeed, when (Asterix creator & Pilote publisher,) René Goscinny decided to publish Sevenoaks in Pilote magazine [running from April – September 1977, issues #35-37], he asked the pair to write a page preparing the reader for what was to come. Floc’h and Rivière duly composed a manifesto (see below) detailing their intentions.

The story we are about to read will not fail to awaken in more than one amateur the nostalgic cloud of memories of the past – I mean the one, still so close to a school which filled our childhood and of which we do not, will never forget the benefits. The stories of Jacobs, each more beautiful than the next, the mysterious episodes of Tintin’s adventures, in short, all this so rich and subtle material that has never ceased to haunt us, Floc’h and me. And if we work with, ceaselessly, the desire to pay homage to these creators who remain masters, our purpose is nonetheless to broaden the vision offered to us by them, to take a certain step back from their lesson, first of all so as not to step on their toes – which would be a bit awkward – but also because we too have to say…

We will see, the reading finished, the curtain fallen, our project wants to make the childish vision lose a little of its innocence, it would also like to create connections between comics and other art forms through the references it would include in its expression. In short, what we are claiming is the right to remove this genre that we love so much from its routine, from some of its rather cutesy habits … And beware of sensitive souls!

But cut off from superfluous words … Someone in the shadows struck the three knocks …

F. Rivière

“It’s very strange that he asked us to write that, no? We had so much respect for Hergé, Jacobs, and others, but we wanted to trace our own way, in a different manner. I think about Walter Scott, the Scottish writer, who said ‘I was born naked and Scottish but I came on Earth to trace my way’ (laughs)…And that’s what we wanted to say, we were going to find our own way. That’s why I speak not about ambition but about artistic expectation.”

Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks would create a sensation upon publication. French literary magazine Les Nouvelles Littéraires were impressed enough to review a comic for the first time in their pages, comparing the book to the work of Jorge Luis Borges and stating that this was not a work for children and even adults would have to read it more than once to truly begin to understand it. Such meta techniques as Floc’h & Rivière were using – Mise en abyme, non-linear narratives, having characters commenting on the story they were in, etc. – were cutting edge at the time, inspired by the Nouveau Roman (new novel) of Alain Robbe-Grillet and others, popular in France in the 70’s. “It’s awful for me when people call me a storyteller, I’m too fond of art, artistic point of views and concepts, to do just a story. The movies I did with Alain Resnais, with drawings inside the film, we felt the same way. Two people who weren’t going to accept just telling a conventional story. We had to do it our way, much more complex. We need a special structure to excite our minds. And that’s a big part of me.”

Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks was the beginning of a working partnership between Floc’h and Rivière that would span decades, and while Floc’h is responsible for the artwork of these books, he also worked with Rivière on the writing as well. It was Floc’h’s own rendering of an E.P. Jacobs Blake & Mortimer cover, placed within a provocative setting, that would catch the attention of his future collaborator. The drawing, entitled ‘L’invitation au voyage’ (‘Invitation to a trip’), depicted a girl in bed reading Jacobs’ L’Énigme de l’Atlantide (‘The Atlantis Mystery’) with a joint sitting on an ashtray next to her. At the end of Floc’h’s first year of EnsAD (Ecole nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs), while the young artist was presenting some of his work to the publishing house Editions Glénat, Rivière, “crazy about Jacobs”, noticed this sketch and the two men got to talking. Rivière would be managing Glénat’s new Marginalia collection, publishing detective, fantasy, and horror novels. Their covers would come to feature some of the great artists of the day – Tardi, Moebius, even Franquin would all contribute one – and Floc’h’s design for Maurice Leblanc’s Les Clefs mystérieuses (‘The Mysterious Keys’) kicked off the Marginalia line in June 1975, to which Floc’h would also later illustrate the cover to Leblanc’s De minuit à sept heures (‘From Midnight To Seven O’Clock’) in October 1978. Although Floc’h passed his exams, he did not return to school the following year, instead, eager to get things moving, he set out on his burgeoning career.

The setting of Une Trilogie Anglaise – and later Blitz, widely thought to be Floc’h & Rivière’s best work – is, as the titles imply, England. The characters travel between life in London and more rural villages (although Sir Malcolm takes place mostly aboard the Titanic). Floc’h’s aforementioned love of England is evident on the page. This fascination was first piqued as a boy seeing the cars coming from across the Channel and considering the English license plates to be much more elegant than the French ones. He was also quite enamoured with the design of the British flag as compared to that of the French. The timeframe of these stories is important too. While Blitz obviously takes place during the Second World War, the tales in Une Trilogie Anglaise open in 1949, 1951, and 1952 sequentially, while harkening back to earlier in the 20th century during the course of their narratives. And it is this era – of stately homes, well-dressed men and women (Floc’h himself is fond of tailored suits), what we might see in old black and white movies – rather than the England of today, or even of 1977 when the first book was published, that appeals to Floc’h. An idea of elegance that has faded from society since the halfway point of the 20th century. And even though Floc’h does not drive, there is affection for the older models of cars, Jaguars et al.

These being mystery stories, they are set within a darker side of England. Perhaps influenced by what Tardi was doing at the time with his Adèle Blanc-Sec series, Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks is immersed in the occult, with the nature of the narrative being magical and taking place around the world of the sinister Black Theatre. Indeed, an interest in the dark arts was present in the real England of the time period that coincides with Sevenoaks, but this first story is the only one where the supernatural enters into their work, the later two books deal with the less mystical topics of murder and espionage.

The protagonists of Une Trilogie Anglaise are journalist/literary critic Sir Francis Albany and mystery writer herself, Olivia Sturgess, whose look owes more than a little to Louise Brooks. The exact nature of their relationship isn’t spelled out within the trilogy but the two are quite close, Albany’s mother even commenting in the third book “you would think Francis and Olivia were brother and sister”. Through the world of literature, the two become involved in investigations suited to their interests and obvious intelligence. By the time of Sir Malcolm, Floc’h’s illustration and the two writers’ storytelling style had become more fully realized, making it the strongest of the three books. Exhibiting a lighter touch, the authors’ playfulness comes with ease, in turn enhancing the story, with flashbacks to the young Albany having something of Tintin about him, and at one point, he’s even dressed up as a bellhop in a nice reference to Spirou.

Besides the natural progress of a young artist getting better at his craft, there is another noticeable difference in the artwork two-thirds of the way through the series. Floc’h had illustrated Sevenoaks using a traditional nib. Then in 1980 he began to use a brush for his advertising work, which of course changed his style. That same year Floc’h created a famous advert in the form of a short comic (also filmed as a 45-second cinema spot) for the throat lozenge company Pullmoll, entitled Le Secret de la Pullmoll Verte (‘The Secret Of The Green Pullmoll’). The opening panel of the strip bears a striking similarity to the first scene of Le Dossier Harding, which he had already begun using a nib and was still illustrating at the time, forcing him to finish the book with the implement and not make a complete switch to brushwork until the finale of the trilogy, Sir Malcolm. But he would not turn back once he discovered what brushes held for him. “That’s the great difference. And it’s quite philosophical because when you take the brush, it becomes like a martial art. It is your spirit that holds a brush. When you use a pen, the pen is touching the paper. There’s no courage at all to do that. No excitement or liberation. But with a brush, if you don’t control it by the force of your spirit, the brush will do something horrible on the paper, splash. And so that was the great changing for me. And to tell the truth, I put my two first books in the garbage because I was ashamed.”

While he may feel that way about the art, Floc’h is pleased to see his early books being released in English, the language of the land they are set in, as they were “done in that spirit”. For the artist, what transforms the trilogy is the introduction À Propos de Francis, which he wrote in 1992, nearly a decade after Une Trilogie Anglaise was completed. “So the trilogy is actually four books,” he laughs. “À Propos de Francis changes everything and you will read the books in a new light. I decided one day that Sir Francis and Olivia would not be characters like Tintin or anyone like that, but that they are real people. So I made a big introduction for Une Trilogie Anglaise saying that Francis Albany is dead. He died of old age.” The book is Olivia’s long obituary for Sir Francis, within which we are told of his friendships with major figures of the 20th century such as David Hockney, W. Somerset Maugham, Noël Coward, complete with illustrated scenes from Albany’s life, including a ten panel Warhol print of his face and the many dust jackets of Sturgess’ mystery novels. This was supposed to put an end to the story, but Floc’h’s creative mind had other plans. “When I completed À Propos de Francis, I said to myself ‘it’s finished, I’m fed up with comics, I went as far as I wanted to go because I had a great project’ but now I’m done. And at once another idea came (laughs). At that time you could go to Sotheby’s or Christie’s and find all the clothes and affairs of, say, the Duke of Westminster or Maria Callas on sale. And I said to myself I will do that. Which became Olivia Sturgess 1914-2004.” At the end of this book which is in fact told as a faux television documentary, there is just such an auction of her belongings. “And after that I said to myself ‘now it’s finished’ (laughs).”

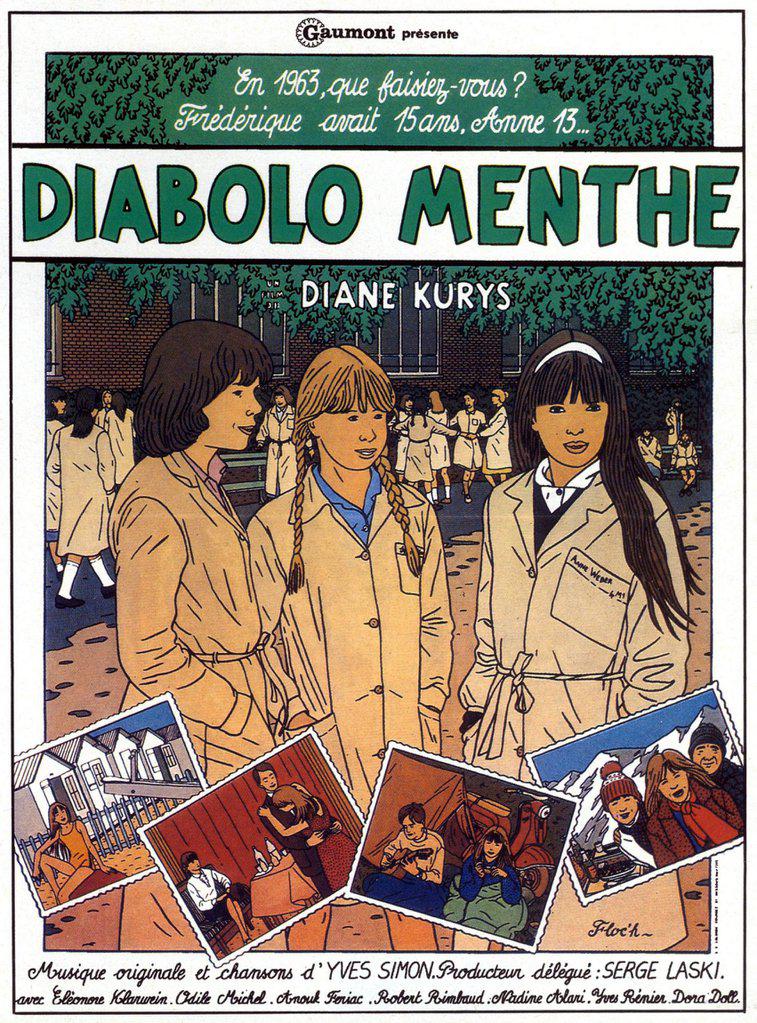

Comics would become only a part of Floc’h’s creative output. Shortly after Sevenoaks appeared in 1977, Floc’h illustrated the film poster for Diane Kurys’ directorial debut Diabolo menthe (‘Peppermint Soda’), the coming-of-age classic often compared to Truffaut’s Les Quatre Cents Coups (‘The 400 Blows’), released in December of that year. He would go on to design the poster for Kurys’ next project Cocktail Molotov (1980), resuming such work in the 90s for the films of Alain Resnais, Woody Allen, and others. While he and Rivière would expand Blitz into another trilogy, with Underground appearing in 1996 and Black-out in 2009, Floc’h became better known as an illustrator than strictly a comics artist. His work has graced covers and interior pages of The New Yorker, Monsieur, Lire, and other magazines, book jackets, record sleeves, and many a luxury ad campaign. He has also produced five books with writer Jean-Luc Fromental. The last collaboration between Floc’h & Rivière was 2013’s Villa Mauresque, once again showing their fondness for the England of the first half of the 20th century, with an illustrated biography of British writer W. Somerset Maugham.

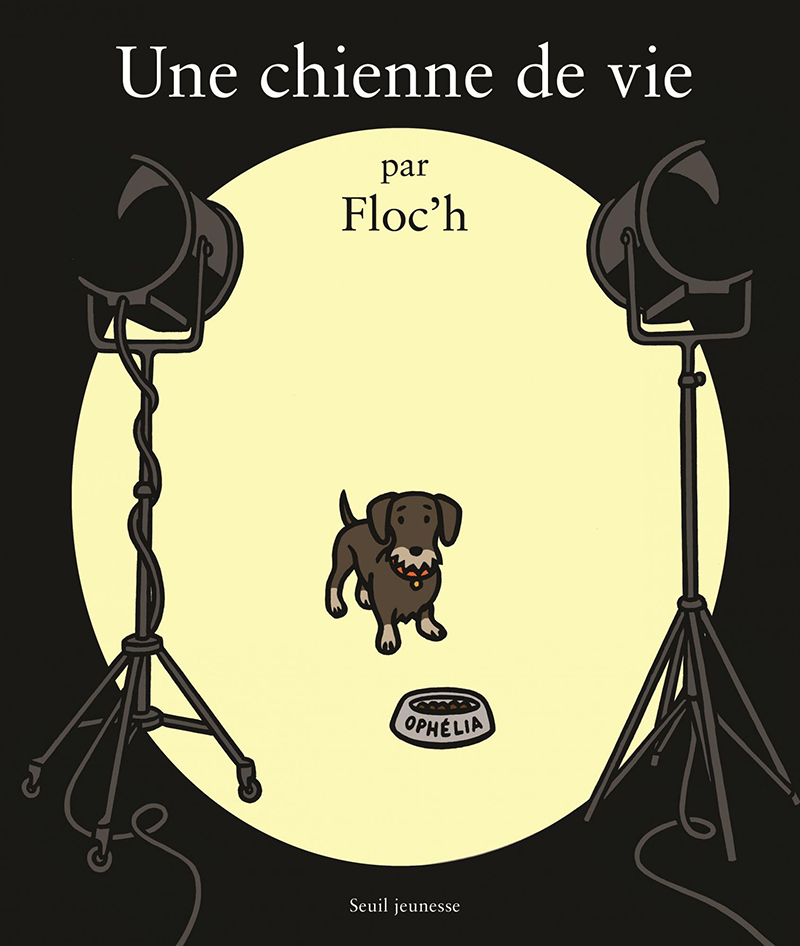

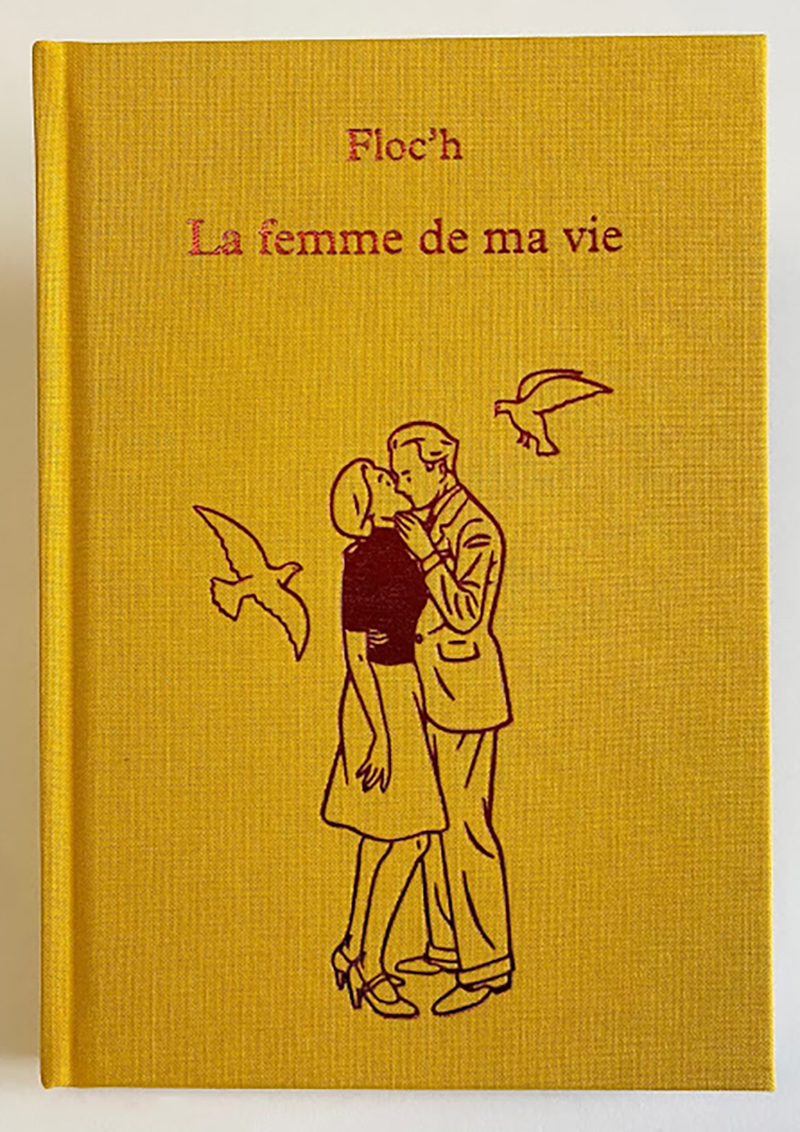

“When I was starting out it seemed there were only two options for guys like me. The first was to write science fiction novels, but I don’t even understand life on Earth so… And the second was to do comics. I decided, a little reluctantly, to tell the truth, to do comics. Why? Because making comics is a lot of work. Even today, I’m surprised that I did all those books. It’s more in my DNA is to make the books I do now, very quickly, one and half months to do a very important book. Like the two I published earlier this year, La femme de ma vie (‘The Woman Of My Life’) and Une chienne de vie (‘A Dog’s Life’), about my wife and my dog. They’re so much fun to do!”

“I knew that I wanted to do books. And the autobiographical fiction I do a lot of today is my pleasure. When you get to be my age, you have a lot of vécu, life experience, so you have a lot to say. But when you are 21, you can’t tell your life, because you have no life. So your life is made of your inspirations.”

Speaking of which, Floc’h is currently working on his own Blake & Mortimer story. “All my life they were asking me and I said ‘no, I’m on Earth to be Floc’h, not to be Jacobs’. But being obliged to stay at home during the lockdown, I decided to do one because I hate what the followers of Jacobs are doing. And it’s not a pain like it was to do comics when I was young, because now I know how to draw (laughs). And looking back, I can see that in the three books of Une Trilogie Anglaise, I made progress in learning how to draw.”

Many thanks to Floc’h for taking the time to speak with me and to the blogger known as Basil Sedbuk, named after a character in Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks, for his expertise assisting the writing of this article. For a vast amount of information on Floc’h (in French), visit Basil’s blog – Floc’h: L’Homme Dans La Foule, named after a 1985 collection of Floc’h’s illustrations.

Cover Image from An English Trilogy © Floc’h & Fançois Rivière / Dargaud