Although German artist Wilhelm Busch was one of the world’s leading comic strip pioneers, today the country’s comic book publishers mainly print licenses from other countries. This has to do with the political situation between 1933 and 1945, which set back the development of all German art forms. For comics it was even more difficult, because of the fact that illustrated stories told with speech bubbles were considered as an American invention, and because the American superheroes – long before the USA entered the war – had chosen the Third Reich and Adolf Hitler as their favorite opponent. Of course there were still cartoons and illustrated stories to read in the Third Reich, but for over a decade speech bubbles were frowned upon as an American bad habit. German artists would not recover from this setback for a long time. For East Germany, this period of abstinence even extended – with one exception – to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

The origins

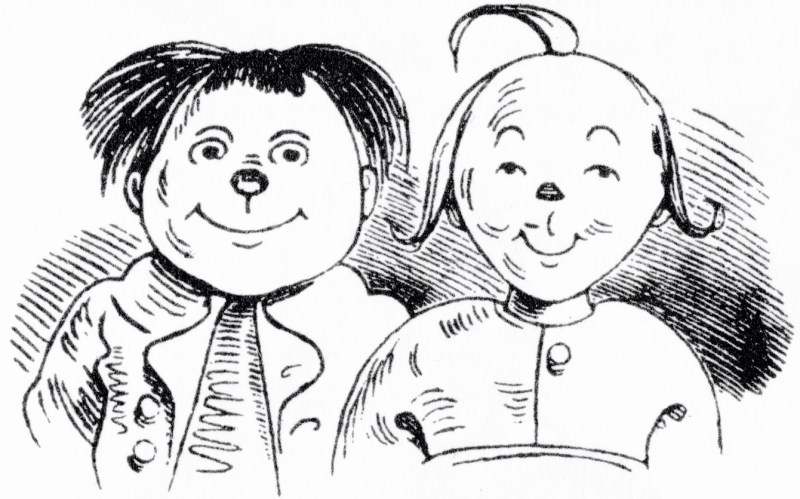

Wilhelm Busch, who lived from 1832 to 1908, was a satirist with a strong sense of black humor, whose stories often showed grotesquely exaggerated brutalities. He pioneered several elements which have become staples of the medium, such as onomatopoeia and the use of motion lines. His most famous work was Max and Moritz: A Story of Seven Boyish Pranks, a tale that originally was meant for an adult audience. It was his publisher who suggested offering it through the children’s book division rather than in the pages of a satirical weekly, as Busch had proposed. The work’s great success proved the publisher right. The book was quickly translated into other languages and inspired lots of other gag cartoons about mischievous children. And Max and Moritz is one of the few stories of its time that is still read by German children today.

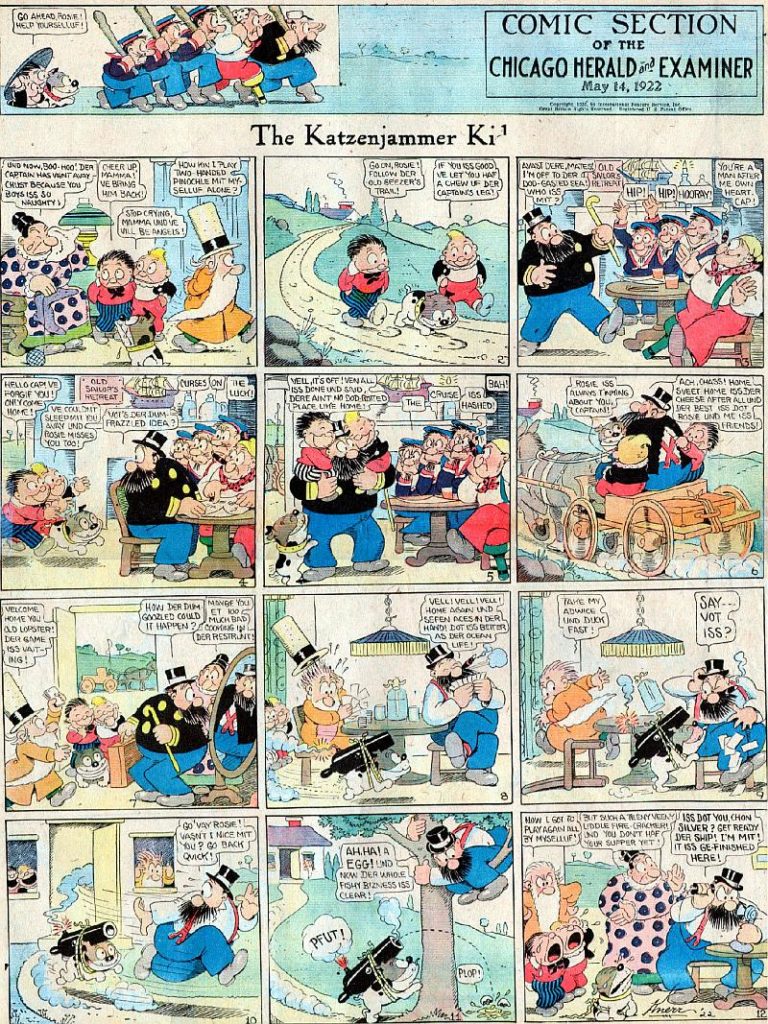

Max and Moritz also became a big inspiration for US comic strips, because in 1897, the German emigrant Rudolph Dirks created a cartoon serial for the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst based on his knowledge of Busch’s famous children book. The Katzenjammer Kids became the first fully developed comic strip in the U.S., with speech balloons. The characters of Hans and Fritz are easily recognizable as counterparts of Busch’s two protagonists. It was this kind of impact that led to Wilhelm Busch frequently being called the godfather of modern comics. As for Dirks, he is the first prominent example in a long line of German artists who had to publish abroad in order to make a living from their work.

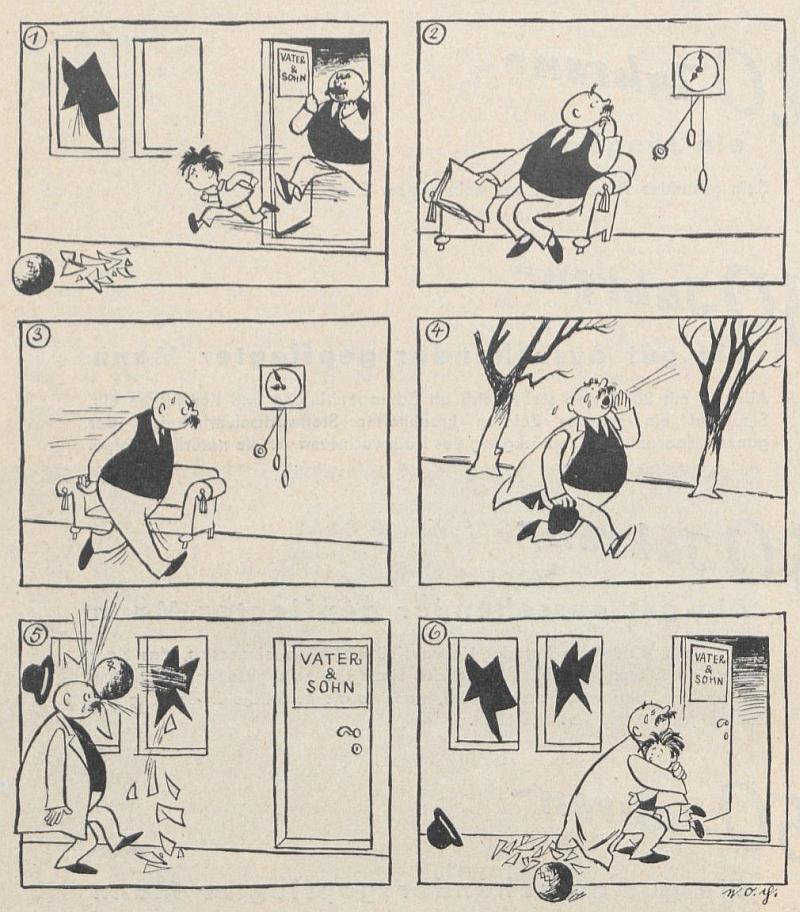

Of all the illustrated stories published during the Third Reich, only one has remained in the memory of German readers to this day: O.E. Plauen‘s (pen name of Erich Ohser) apolitical one-pagers Father and Son. O.E. Plauen, who often illustrated for social democratic newspapers during the Weimar Republic (including a cartoon in which a drunken man relieves himself, drawing a swastika in the snow), was banned from working under the Reich. It was only through the intercession of Erich Kästner, who at times had to work under a pseudonym himself, that he was given the opportunity to draw his wordless stories, which tell of the amusing everyday adventures of a boy and his father. Father and Son was a great success right from the start, with a first anthology selling 90,000 copies in a short space of time. But the sensitive Plauen could never resign himself to working for the regime he hated, even if it was in order to survive. In his private life he often told political jokes, which was to be his undoing in March 1944. Accused of defaming Goebbels and Himmler, O.E. Plauen committed suicide the morning before his first day of trial.

The post-war period in West Germany

After the lost war, the hunger for apolitical entertainment among the German population was great. Children and adults alike wanted to distract themselves from the world that lay in ruins around them. Money was short, but newspapers, magazines, and pulp novels were still booming. After reading, many issues were exchanged or passed on to others. Comic books were first and foremost introduced by American GIs, who gave their copies away to children after reading. Initial attempts by German publishers to enter the comic book licensing business failed miserably. The situation was even worse with in-house productions, which often did not go beyond the first edition. Even the first attempt at a German edition of Superman (as Supermann) disappeared from the market in 1950 after just three black-and-white issues. Publishers simply lacked the know-how to deal with this new medium. It was not until the introduction of the four-color Micky Maus (Mickey Mouse) in September 1951 that German comics began to catch on. Of course, it helped that the population still knew the Disney characters from the pre-war period, and animated cartoons were now shown in West German cinemas again.

It was the Lehning publishing house from Hannover that recognized this gap in the domestic market. Already present on the market since 1948 with magazines and pulp novels, publisher Walter Lehning discovered a new kind of comic book during a vacation in Italy, small editions the size of a comic strip. This tiny format with black and white content could be produced very cheaply and brought onto the market at a low price. Equipped with a number of popular Italian series, Lehning launched his first western, boxer, and jungle stories in 1953, books which took many German children, who were still playing in the ruins of the war, to a more exciting world. Shortly after their successful launch, Lehning received a visit from Hansrudi Wäscher, a Hannover-based illustrator who had spent his childhood in Italian-speaking Lugano (Switzerland) and was therefore very familiar with the comic strip format, which Walter Lehning had named Piccolos (“small” in Italian) for the German market. Drawing such comic books himself had been Wäscher’s dream since his childhood days, and by 1949, during his studies at the Werkkunstschule in Hannover, he had already produced a complete science-fiction comic book with the title Battle for Mars.

Such an artist could only be welcomed with open arms by Walter Lehning, and so the knight series Sigurd hit the market shortly thereafter, both written and drawn by Hansrudi Wäscher. Later, he also took over the series Akim, Son of the Jungle, because the Italian licensed material repeatedly provoked trouble with the Bonner Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Schriften, a state authority that could ban magazines and books if suspected of endangering the welfare of children. Many German adults were in agreement with the critical theories of psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, whose work had been translated from English into German. While funnies like Micky Maus in those years were seen as harmless amusement, the state authorities saw in Lehning’s western and jungle adventures — in which fistfights and gunfights were the order of the day — a serious guide to hooliganism, a noxious influence surpassed only by Rock ‘n’ Roll. No other publisher’s comics were as frequently banned as Lehning’s, nevertheless he published successfully for 15 years. Lehning’s first eight Piccolo series reached a total weekly circulation of half a million copies at the end of 1953. Hansrudi Wäscher worked for Lehning until the publishing house vanished from the market in 1969.

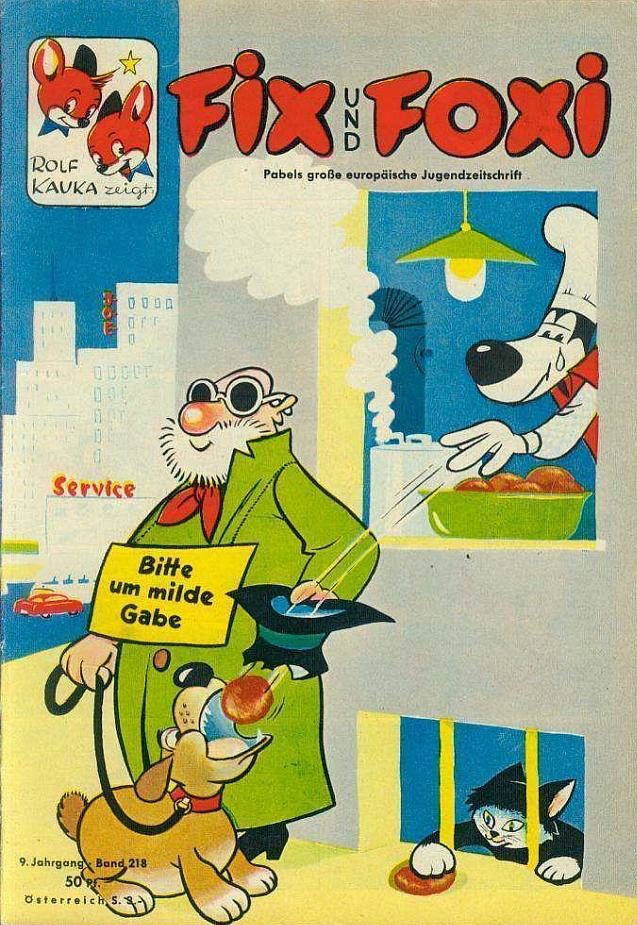

As a German counterpart to Micky Maus, the Munich-based Fix & Foxi was first published in May 1953, a periodical that would be illustrated by numerous German artists over the decades. Local artists like Werner Hierl, Josef Braunmüller, Helmuth Huth, and Becker-Kasch soon received support from Yugoslavian colleagues like Walter Neugebauer, Vlado Magdic, and Branco Karabajić, who moved to Munich to work for the magazine. Fix & Foxi was first and foremost a publication for funnies, but it also published realistic westerns and dramas. Publisher Rolf Kauka was also one of the first to recognize the high value of Franco-Belgian comic licenses and to bring series like Spirou or The Smurfs closer to German readers.

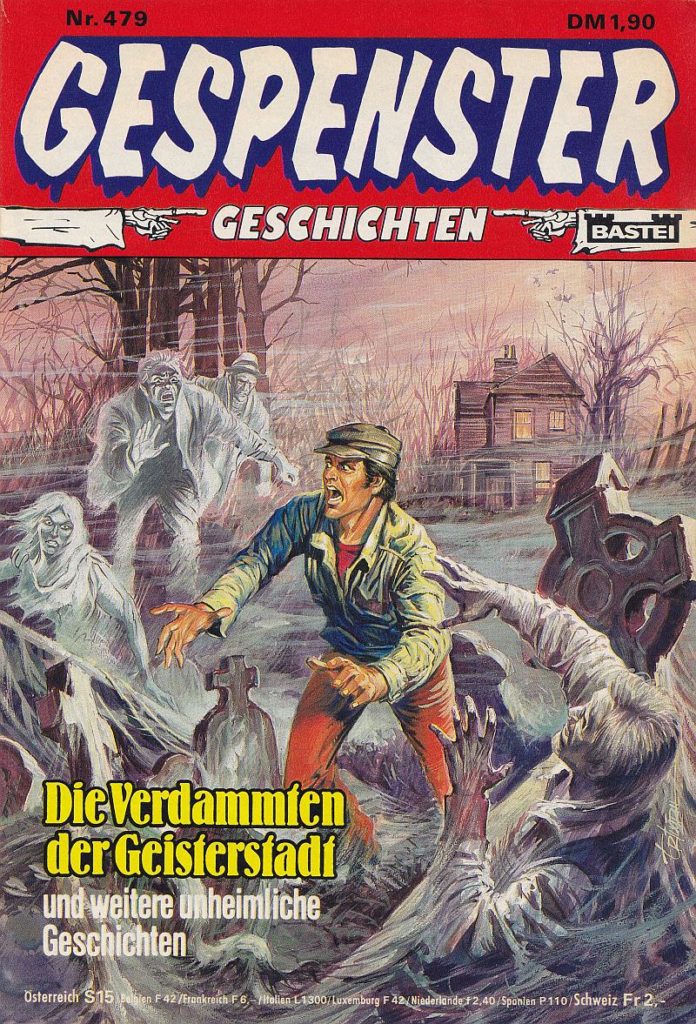

Later on, Bastei Verlag established itself as a player that knew in particular how to use Flemish licenses for its own purposes. It achieved huge print runs into the 1980s with western comics such as Lasso, Bessy, and Silberpfeil. When the available licensed material was no longer sufficient due to the speed of publication, many foreign teams such as the studio of Willy Vandersteen or the Italian studio Alberto Giolitti stepped in, producing exclusively for Bastei. This led to the typical German phenomenon of those years, in which German authors wrote comic scripts that would be drawn by Italian, Spanish, or Belgian artists for the German market. The same applies to the Bastei magazine Gespenster Geschichten (Ghost Stories), which, after the material from US anthologies such as Boris Karloff – Tales of Mystery, Grimm’s Ghost Stories, or The Twilight Zone had been used up, started to commission Spanish series.

In addition to the busy teams of German writers, German artists also occasionally gave a guest performance in Gespenster Geschichten, but in the long run they worked too slow to make a living in Germany on their wages, which were no higher than for their Spanish colleagues. Only Hansrudi Wäscher managed to establish himself permanently at Bastei after the bankruptcy of Lehning Verlag, first with the western series Buffalo Bill, and later on with contributions for Gespenster Geschichten. Many German comic fans, who grew up with American superheroes or the Franco-Belgian classics from 1970 onwards, see Hansrudi Wäscher as an artist of inferior quality who could shine only as long as there were no possibilities for comparison. Thanks to his high working speed, however, he was able to make a living in Germany for decades by drawing comics, while many of his colleagues, who applied higher quality standards to themselves and their work, soon had to look for other fields of activity or set off abroad.

CONTINUE TO PART 2

Text by Bernd Frenz (www.berndfrenz.de). Beginning as a comics journalist in 1990 for the magazine PANEL (winner of the Prix de la bande dessinée alternative, or Alternative Comics Prize, in 1999), Frenz has since worked for all major German comics journals, including Alfonz, Comic Report, Comixene, Hit Comics, and Reddition.

Header image: The Katzenjammer Kids © Harold Knerr