Novelist, translator and writer Víctor Mora would go down down in comics history thanks to the creation of El Capitán Trueno (1955), one of the public’s most beloved works from the mid-20th century. This should not come as a surprise considering that Mora’s hero was unique right from the start. In the eyes of the writer, who originally used the pseudonym Victor Alcazar, Capitán Trueno was an agitator, which is why in his adventures he often attacks the established order to bring about justice.

In June 1956, Trueno’s adventures started to be published in landscape format. Some time later, the protagonist was included in the pages of the weekly Pulgarcito, contributing to the collection’s spectacular success and facilitating the design of new magazines with his feats. The first of these new formats was El Capitán Trueno Extra (1960), which was adapted to market demands of the time. Later on, Album Gigante El Capitán Trueno (1964) and Trueno Color (1969) would be published. Trueno Color, of continued interest to Spanish readers, was reissued in 1987.

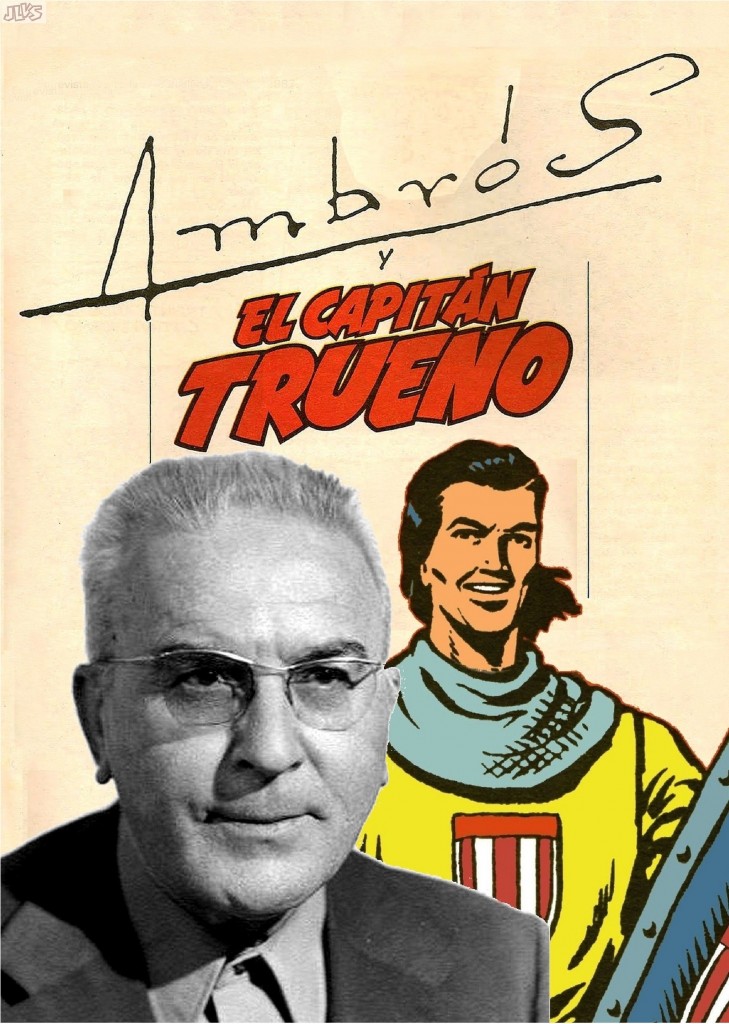

Although the main cartoonist behind Capitán Trueno was Miguel Ambrosio Zaragoza, also known as “Ambros,” growing demand for the comic led to the hiring of other talented artists. Beaumont, Angel Pardo, Adolfo Buylla, Tomás Marco, Juan Martínez Osete, Francisco Fuentes Man, Luis Bermejo, Jesús Blasco and John Burns are some of the other artists who participated in this series’ extensive catalog.

In 1958, the publishing house Bruguera took advantage of Capitán Trueno’s popularity to launch a new series, El Jabato, with scripts by Mora and drawings by Francisco Darnis in collaboration with Juan Martínez Osete. There are considerable similarities between the protagonists of both comics. As was the standard of the era, the original comics of the first series were in landscape format with dimensions of 17 by 24 centimeters. First published in 1958, there are a total of 381 issues.

As highlighted by Román Gubern, “without exaggerating, it is possible to refer to this period as a true Golden Age of the medium, not overshadowed by strict surveillance or censorship or competition from local television.”

From this moment onwards, Spanish comics would go through a strange time marked almost exclusively by Trinca (1970), a publication that was, in the words of Mariano Ayuso y Antonio Lara, “born with a very clear purpose, to try to create a high-quality publication with the best cartoonists, writers and collaborators, plenty of colored pages, a meticulous printing job and a modern look.”

The pages of Trinca, a recruitment tool for the new Spanish comics, contained the work of notable authors such as Antonio Hernández Palacios (Manos Kelly, 1970; La paga del soldado, 1972), José Bielsa (El rally de los 5 continentes, 1971) and Víctor de la Fuente (Haxtur, 1971; Mathai d’Or, 1972) among others.

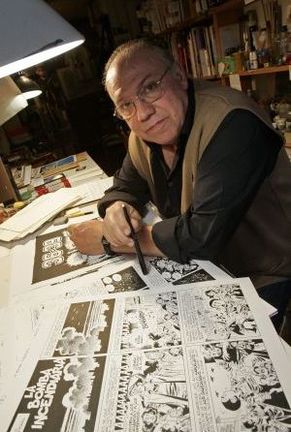

Despite the intellectual flight from the country, some authors managed to reconcile their work in Spain with their international ambitions. This was the case of Carlos Giménez (Gringo, 1963; Delta 99, 1968), Esteban Maroto (Cinco por infinito, 1968), and especially Enric Sió (Agardhi, 1969; Mara, 1970). Besides providing the cartoonists with ample professional benefits, the international publishing world’s support familiarized them with freedom they didn’t yet enjoy in their own country. Works such as Las crónicas del Sin Nombre (1973) by Luis García and Víctor Mora, and Mac Coy, drawn by Hernández Palacios with text by France’s Jean-Pierre Gourmelen, emerged from this world. Both comics were published in the magazine Pilote by publishing house Dargaud.

The climate of the time was embodied by one of its chief spokesmen, Josep Toutain: “We are conscious of what little there is to tell about Spanish comics from 1950 to 1975 and we are saddened by this. During these 25 years, the great authors forged before and after the Spanish Civil War were forced for political and economic reasons to become mercenaries for foreign publishing houses. (…)

Censorship, low prices and a lack of job opportunities led to the massive migration of Spanish artists to France and South America at the beginning of the 1950s. The arrival of new publishing houses curtailed physical migration but made it easier for intellectual flight. These were outstanding houses like Creaciones Editoriales–A.L.I. (Bruguera), Selecciones Ilustradas–S.I. Artists (Toutain), Bardon Art (Macabich), The Illustrated (Ferraz) and Studiortega (Ortega). (…)

“For more than 25 years, the most diverse French publications have enriched themselves with contributions by Spanish artists, either permanent residents in Paris or hired via these publishing houses. Germany, the Scandinavian countries and Italy employed so many Spanish artists that, in some cases, this led foreign editors to sponsor offices or publishing houses in Spain. During the 1960s, the magazines for ‘teenagers’ in the UK, which achieved the largest circulation in the history of British comics, were saturated by the work of cartoonists residing in Barcelona. In the 1970s, more than 30 Spanish artists would surprise the US—the country considered to be the birthplace of comics—with Europe’s new comics aesthetics for adults. Works made in Spain reached countries as distant as Australia, Brazil, South Africa, India, Yugoslavia and Greece.”

Nonetheless, humor comics, usually for children, continued to lead in the Spanish market. Mortadelo y Filemón agencia de información (1958) by Francisco Ibáñez was one of the most popular comics in Spain at the time, as well as Pepe Gotera y Otilio (1966). Juan “Raf” Rafart continued on this parallel path with titles such as Campeonio (1969) and Sir Tim O’Theo (1971).

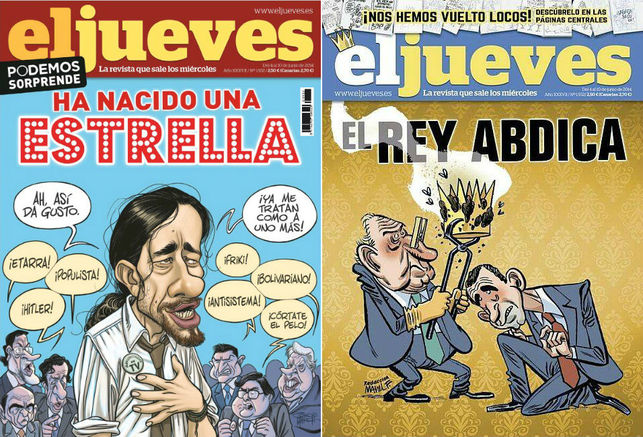

The democratic transition favored the gradual emergence of satirical magazines that, free of censorship, mocked the national reality. El Papus (1973) and El Jueves (1977) achieved this thanks to the work of authors like Ramón “Ivá” Tosas, Jordi “Ja” Amorós and Oscar Nebreda, known simply as “Oscar.”

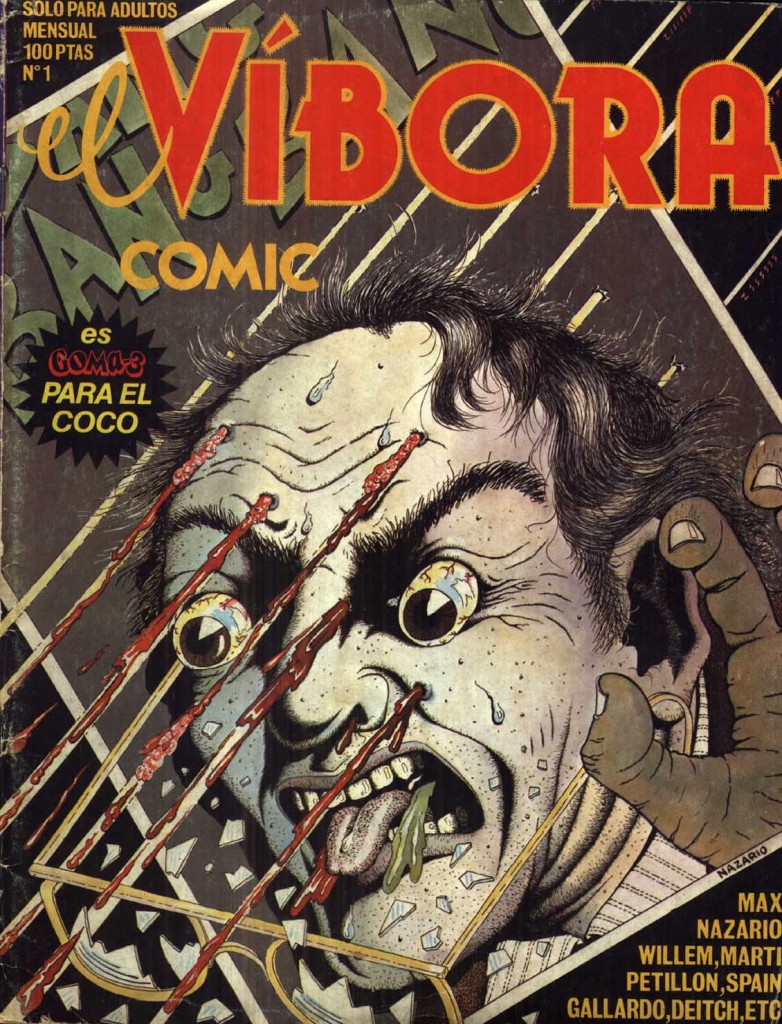

With the arrival of the magazine El Víbora (1979), new ingredients—in many cases countercultural ones—were integrated into Spanish comics. As noted by Vázquez de Parga: “They are marginal but not marginalized comics, in the sense that they look into social segments and issues that fall outside the official reality. They are critical and even antisocial comics that go far beyond satire… They attack the establishment’s structure, telling long stories that use violence, sex and drugs not as ends in themselves but as means to reflect a segment of reality, and that employ a colloquial language, precisely that of the marginalized segments they portray.”

Makoki (1978) by Felipe Borrayo, Miguel Angel Gallardo and Juan José López Mediavilla was this style’s most faithful representative, followed by Anarcoma (1979) by Nazario Luque and Roberto el Carca (1980) by Antonio Pamies.

As required by this new phase, adult magazines incorporated a dose of eroticism and violence into conventional adventure stories. Totem (1977), 1984 (1978), Creepy (1979), Cimoc (1981), Cairo (1981) and Rambla (1982) starred in this era referred to by some writers as “the Spanish comics boom.” Alongside the growth of the comics market, magazines that analyze comics also started appearing, as was the case of Sunday (1976) and Bang! (1977).

Norma Editorial’s publications followed Josep Toutain’s publications in Barcelona. Ediciones B, after taking over Bruguera, released Co & Co (1993). In Madrid, both La Luna de Madrid (1983) and Madriz (1984) served as a launching pad for young artists who also explored their creative ambitions in fanzines and prozines. (See Hernández Cava, F.: “De Madriz a El ojo clínico,” in AA.VV.: Tebeos: los primeros 100 años. Madrid. Biblioteca Nacional/Anaya. 1996, p. 249 and subsequent pages.)

Nevertheless, disenchantment followed euphoria as confirmed in the title of the article “De la viñeta al paro” (“From Comics to Unemployment”), which captured how the 1990s marked a crisis in Spanish comics:

“There are new authors, there is quality and there is will. But there is no comics industry, no money and no readership. That is why the new generation of cartoonists has it tough. They rely on independent publishing houses. But it’s not enough. This is the overall picture.

“The large publishing houses (Planeta, La Cúpula, Norma, Glénat) take few risks. Norma and Glénat go with the safe bet: they publish established foreigners. Mega-publishing house Planeta has a small space reserved for newbies: Línea laberinto. Then there is La Cúpula, veteran publisher of El Víbora, Kiss and, for the past four years, the collection Brut, which has featured authors such as M.A. Martín, Arcas and Acuña, and Beto Hernández.

Their economic standing would allow them to take more risks (it is more expensive to publish a new local author than to buy the rights for a foreign one). But this year’s news sticks to tradition: the big publishers will continue to bet on alternative North American comics (Jason Lutes, Peter Bagge, Seth). Locals will have to keep waiting.” (“El País de las Tentaciones,” 19/3/1999, pp. 28-29.)

The new century began with two interesting phenomena: the appearance of small publishers that bet on alternative and independent comics, and the international launch of artists and writers whose professional futures took flight thanks to major publishers such as Marvel and DC. This situation was not unique—recall the authors of Selecciones Ilustradas during the 1970s—but rather stemmed from a new international context: the globalization of cultural industries.

From “Historia del cómic español” by Emilio C. García Fernández and Guzmán Urrero Peña for The Cult. Translated from the original Spanish by Storyline Creatives.

Header image from El Capitán Trueno no. 1 (Editorial Bruguera, 1956)