The Hedgehog

In 1989 we began building a new, free, prosperous Poland, and — so hoped all fans — a new, free, and prosperous comics market. Censorship was no more; the borders had been opened; and demand, rather than the whims of Party secretaries, began to determine supply.

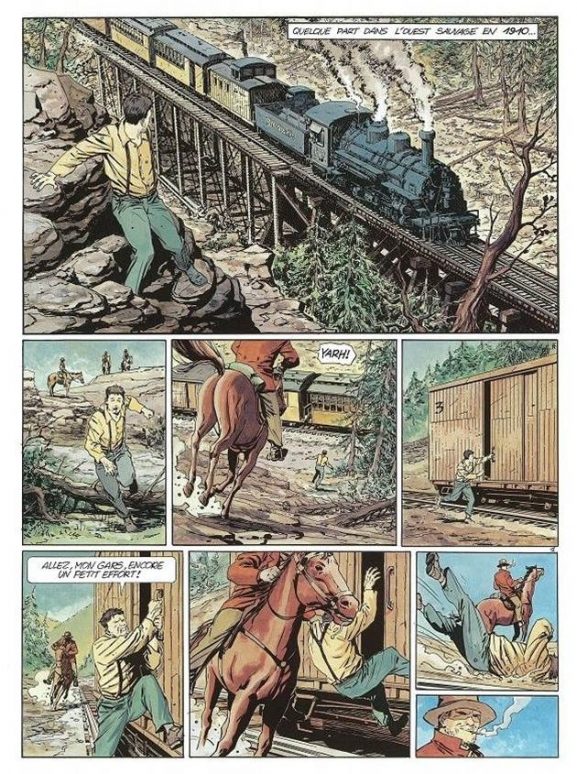

The beginning was promising. For the first time since 1939, comics featured American superheroes (Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, X-Men, etc.). Several publications were imported from France and Belgium (Tintin, Chninkel, Valerian, Asterix, Lucky Luke). Young Polish artists began not only drawing their own stories but also publishing magazines (AQQ, Superboom, Awantura), organizing conventions, and fostering fandom. Comics for children were produced on a mass basis (among them the Disney weekly Donald Duck). The two most important artists to debut in this pioneering period are Krzysztof Gawronkiewicz and Przemysław Truściński. The major event in the field, the International Festival of Comics in Łódź that is held every autumn (led from the start by the same man, Adam Radoń), will celebrate its twenty-eighth year in 2017.

But lean times followed the boom. It turned out that the enormous readership of comics in communist Poland (editions ran in the hundreds of thousands of copies) had partially resulted from the lack of other entertainment for young consumers. Now comics had to compete with movies, computer games, and popular fiction. More and more publishers closed; many Polish comic artists could display their work only at shows and festivals.

But in the second half of the 1990s, comics regained their lost ground. Their advances came from several directions. The leader was Egmont, the publisher for whom I have had the pleasure of working for twenty-two years. Sales of Donald Duck reached two hundred thousand copies a week. In 1998, Egmont introduced the monthly magazine The World of Comics, followed by many French, American, and Japanese titles and reprints of Polish classics, in addition to new Polish titles (Egmont has published roughly 1,500 comic books to date).

Small family-run presses — JPF and Waneko — brought manga to the market. Other new publishers — including Kultura Gniewu, Mucha, Taurus, JG studio and many more — started their activity and have been on the market until now. They publish books from all countries and in all styles – from superhero and genre bandes dessinées to graphic novels and artistic comics. In terms of proposals from Polish authors, too, the national market developed progressively.

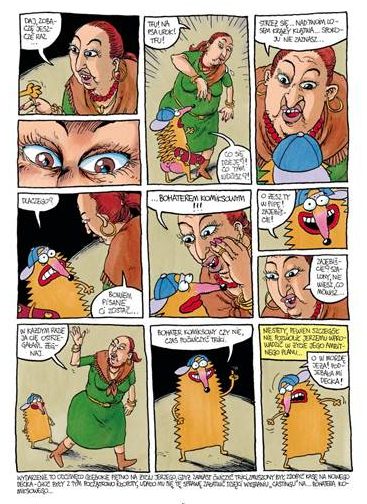

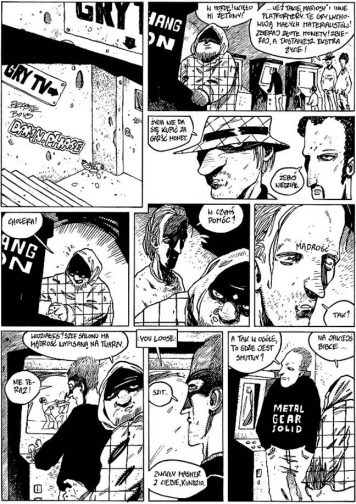

Produkt, an in-your-face alternative magazine, brought out a group of new artists and series — among them Michał Śledziński’s Freedom Residences and Minkiewicz’s Wilq (Wulf). With the third title — Jeż Jerzy (George the Hedgehog; the Polish is pronounced “Yezh Yezhi”) by Tomasz Lew Leśniak and Rafał Skarżycki — they set the tone for young readers of comics. This work was carelessly drawn, but it was humorous, and it captured accurately the life of modern Poland, especially the world of teenagers and people in their twenties: their aspirations, their problems, their joys. At last free of censors, comics could laugh at unpopular politicians, national shortcomings, and general human stupidity.

Let’s take a closer look at George. This spiky hedgehog always wears a baseball cap. He gets around by skateboard, smokes pot, drinks beer, hits on women, fights with skinheads. When environmental activists urge him to return to the forest and live in harmony with nature, he replies, “To the forest? Me without a cold brew, a hot body, and my board? Are you out of your mind?”

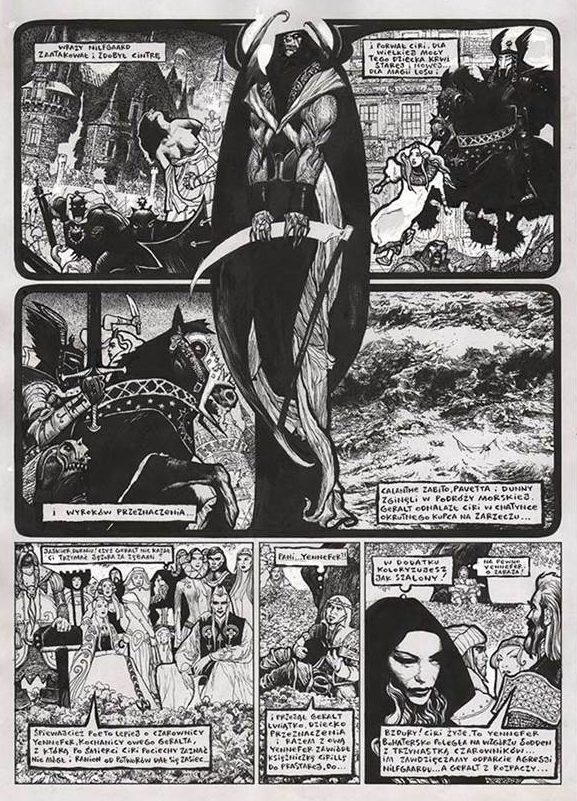

The new realistic comics — in the genres of mystery, fantasy, or adventure — are less popular, although their creators are becoming more successful. Polish superheroes were even created (e.g. Jan the Haughty by Jakub Kijuc). A few Polish artists and writers (e.g. Robert Adler, Piotr Kowalski, Katarzyna Niemczyk, Marek Oleksicki, and Marzena Sowa, the author of Marzi) also published books with major French and US publishers.

The offer for more mature audiences was directed by authors of artistic comics or graphic novels (e.g. Mateusz Skutnik, Wojciech Świdzieniewski, Maciej Sieńczyk, Marcin Podolec). Many interesting comic anthologies were published as well, including women’s comics, and titles devoted to such various topics as World War II, football, and the ethical dilemmas of modern medicine.

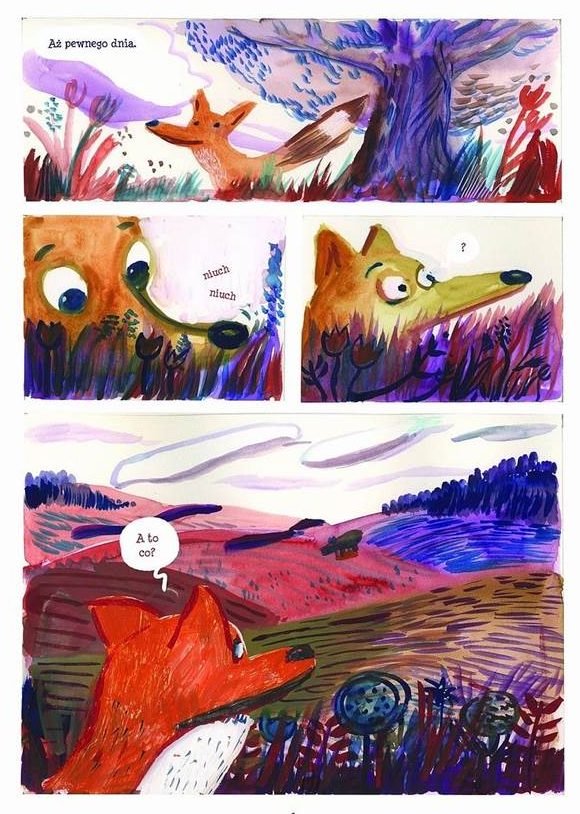

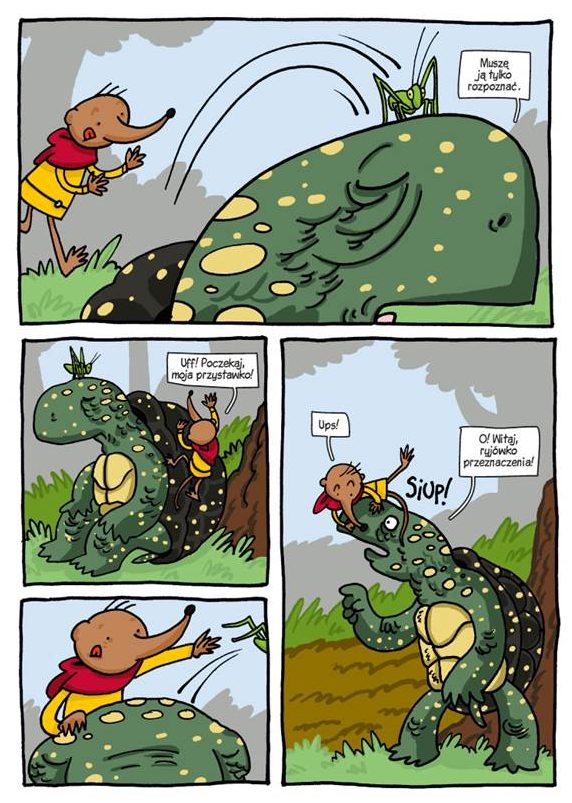

The children’s segment was also revived, a trend that has accelerated in recent years. Comic books such as Tomasz Samojlik’s The Shrew of Destiny, Berenika Kołomycka Fox and the Boar, Łauma by Karol Kalinowski and Piotr and Bednarczyk’s Lil and Put (and many more) have hit the bookshops. Movie or TV adaptations of a few of them are also in development now. Overall, the Polish children’s classic is still being re-established, but making good progress. A continuation of the legendary Kajko i Kokosz has been created by new artists with considerable commercial success, and the grand master, Papcio Chmiel, is creating (at 94 years old!) new books featuring the adventures of Tytus (Tytus, Romek i A’Tomek).

Polish comics have also become an interesting medium for institutions promoting culture and historical knowledge, such as the Institute of National Remembrance, the Warsaw Uprising Museum, and the Museum of the Second World War. They support publishing interesting documentary and educational comic books. Finally, the panorama is complemented by press comics (mainly political), web comics, and independent fanzines.

The current situation of comics in Poland is good. Several publishers are considering bringing out new titles from the heartlands of world comics, France, the United States, and Japan. We also have our own Polish rising stars, with some young illustrators beginning to sell their work in Europe and the U.S. The media cover important publishing events, public appearances of artists, and comic conventions. The market has grown extremely fast in last three years, (in all areas – BD, US comics, and manga). Polish comics and pop culture conventions now draw up to 20,000-40,000 visitors. We have hosted as guests of honor such world-famous creators as Andreas, Simon Bisley, Neil Gaiman, Dave McKean, Regis Loisel, Moebius, Milo Manara, Marvano, Grzegorz Rosiński, Stan Sakai, Jean Van Hamme, and Yslaire.

Yet comics in Poland face a number of problems. Although they are often seen as a “mass-culture,” popular phenomenon, they still are more of a medium for hobbyists (except for classic series like Asterix, Kajko i Kokosz, and Tytus). The price of comics is in fact a little lower than in Western Europe, but it remains high for the average Polish consumer. Each new volume of Thorgal may sell twenty thousand copies in the course of a year, but an average print run is in the range of one to two thousand copies. Even the most popular young Polish authors cannot support themselves by writing comics — they live by drawing storyboards for ad agencies, and their creative work is done after hours. Much of the media still does not recognize the existence of this art form, and many critics perpetuate the old cultural prejudice, seeing comics as something inferior — not understanding their language, aesthetics, and special qualities, their difference from literature or film. Reviews of weak films or books often characterize them as being on a comic book — read “primitive,” “simple,” “infantile” — level.

The Shrew and others…

The future? I am an optimist. How could I not be?

When I was ten I was wandering from kiosk to kiosk for the latest issue of World of Youth or Relax and each comic page was a treasure. Now I’m fifty-years-old and I’m responsible for the largest imprint of comics on the Polish market, where we have published practically all the authors whose adventure stories I had combed the streets for decades earlier.

I was thirty when we started the comic line in Egmont – at that time fewer than 100 comic books (BD, US comics, manga, and fanzines) were published in Poland each year.

Today I see on the shelves of Polish bookstores a near complete collection of European and American classics. I can read translations of many interesting novelties. I find information about comics in the most important Polish newspapers. I note the Polish names in the catalogs of foreign presses. It’s the best time for the Polish comic fan, ever.

Thanks to the hard work of artists, publishers, editors, festival organizers, and promotors of culture (and the loyalty of fans, of course), we have created in our country all that we need for comics to be a long-term success: the market, the community of fans, the lifestyle, and an active art genre.

Next year we will celebrate the 100th anniversary of Polish comics. We will do our best to show the roots and the broad presence of the genre to fans and children, to librarians and people interested in art, to book readers and teachers, both during our Polish conventions and international exhibitions.

We remember our past but at the same time we are building the future. It’s precisely what millions of Poles have been doing across the whole country in the last twenty-eight years of freedom.

Provided they can avoid politics and external invasions, I believe comics as both an art form and a business will continue to develop in Poland.

RETURN TO PART 1

Text by Tomasz Kołodziejczak. Mr. Kołodziejczak is a writer, publisher, and promoter of culture. Since making his debut in 1985, he has published six novels and dozens of short stories, in addition to creating comics and board games, and writing computer game scenarios. He is considered to be one of the most important authors of Polish fantasy, and his writings have been translated into English, Czech, Lithuanian, Russian, and Ukrainian. Since 1995 he has been working for the publishing house Egmont Poland.

Header image: Kajko i Kokosz © Janusz Christa