The Goat

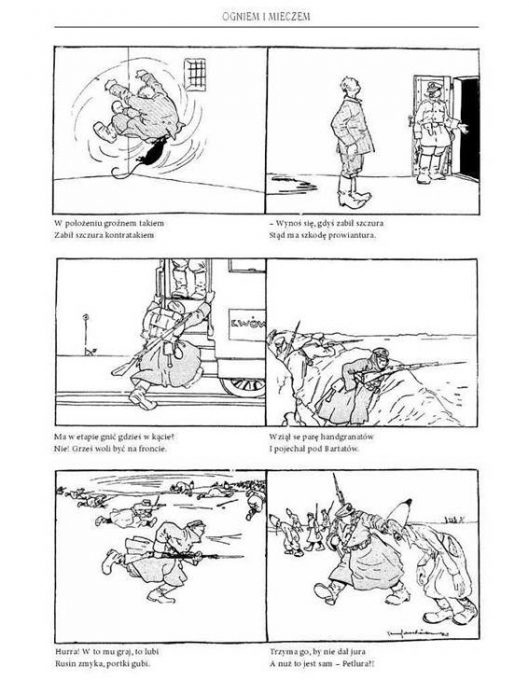

Polish comics began in 1919 with the publication in the Lvov satirical weekly Szczutek (“Fillip”) of With Fire and Sword – The Adventures of Mad Grześ (written by Stanisław Wasylewski and illustrated by Kamil Mackiewicz) about a young soldier who battles enemies of Poland on various fronts. For the next twenty years the comics market developed slowly but systematically. Comics were published in magazines for both children and adults. Most were imported — among them Prince Valiant, Tarzan, and Mickey Mouse. The range of themes was broad, from propaganda and satire, gore and science fiction to tales for children. The dominant form was “paracomics,” with the text not in balloons but under the images, and often in rhyme.

The longest pre-war comic cycle was the satirical Adventures of Unemployed Froncek by Franciszek Struzik, appearing continuously for more than seven years (2,600 episodes!).

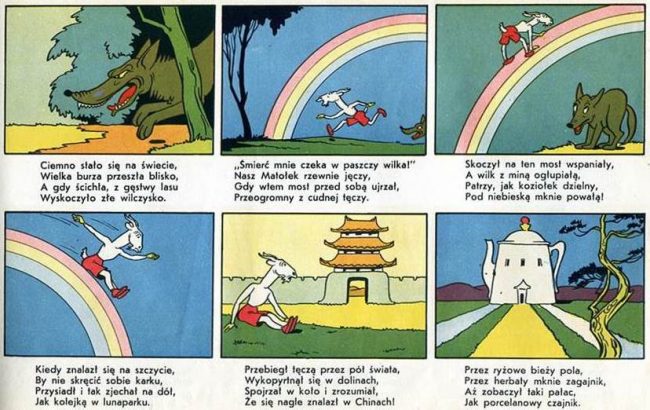

But without a doubt the most popular of the Polish comics before World War II was Kornel Makuszynski and Marian Walentynowicz’s Goat Matołek (Dopey Goat), about the adventures of a goat in search of the city Pacanów (“Blockhead City”). Now it is considered a children’s classic, but opinions differed when it debuted. Literary News wrote, “These are the adventures not only of a moron but also for morons… This is trash of the common variety.” Similar criticism of comics sometimes persists in the Polish media to this day.

Under the German occupation of 1939, the Polish comics industry came to a halt. Shortly after the war, from 1945 to 1948, a few publishers tried to bring back prewar titles such as New World of Adventures, but the Communist regime did not like comics: they were a product of the vile West, of rotten pop culture. And so their publication was forbidden.

In 1952, at the peak of Stalinism in Poland, the weekly Film wrote about American comics: “Supermen, astroboys, Tarzans, and Jack Carters are spreading among young people the cult of military invasion, racism, sadism, and sensuality, as well as the myth of ‘science’ used to exterminate the human race.”

The Monkey

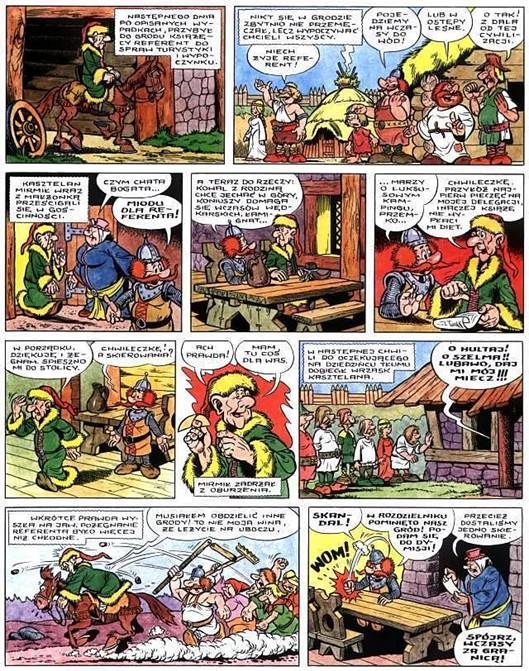

That attitude changed only after the 1956 post-Stalinism thaw. The comics weekly Adventure was allowed to publish its first issue in ten years: it contained adventure, crime, and gore, and featured the debut of Janusz Christa, who would go on to create one of the most popular Polish comics ever, Kajko and Kokosz. Politics also drove the appearance in the scout magazine World of Youth of Tytus, Romek, and A’Tomek, a series about the chimpanzee astronaut Titus, created in 1957 by Henryk Jerzy Chmielewski (nicknamed Papcio Chmiel). The strip was approved only after the successful mission of the first Sputnik satellite in 1956: the government decided it was worth promoting space travel to young people, a decision that also led to official approval of the publication of science fiction. Titus is unquestionably the most important and popular hero of Polish comics ever.

The authorities still disapproved of comics. Adventure was closed after only two years. The official reason was the paper shortage, but more likely the editors had seen too many articles and memoirs about World War II that dealt not with the Soviet army but with the Polish underground resistance and with the Poles in the West who fought.

The Communists disliked comics, but recognized they could be used as propaganda. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a few classic series were launched: the adventures of Captain Kloss, a Polish-Soviet agent who worked as a superhero spy in German Abwera in World War II; Podziemny Front, about Communist partisan fighters; and Captain Żbik (“Captain Wildcat”), a capable and handsome militiaman, one of the good guys, who solves crimes and helps children. Through these exemplary characters, young readers and develop a positive attitude toward the system.

The main sources of comics in the 1960s and 1970s were World of Youth, which came out a few times a week, and local papers. To this day I have at home — like many lovers of comics my age in Poland — thick folders in which I pasted comics episodes cut from the pages of World of Youth. When I showed them to my eight-year-old daughter, she asked, “Daddy, why didn’t you go to the kiosk and buy a regular comic book?” Growing up, thankfully, in a normal world, she couldn’t understand my emotional account of searching many hours for a kiosk in Warsaw that had the latest issue of a desired magazine.

Some of the comics artists of the 1960s and 1970s made it into the Polish comics Hall of Fame. Grzegorz Rosiński drew Thorgal for many years and is a great star in the European market. Tadeusz Baranowski (Orient Man, Kudłaczek and Bąbelek [Shaggy and Bubbles]) is a master of the absurd who plays with language and with the formal layout of frames and panels. Szarlota Pawel created a charming fantasy world about everyday life in Poland in Jonka, Jonek, and Kleks (Jonka, Jonek, and Spot). Janusz Christa made Kajtek and Koko in Space (more than three years of daily strips) and the popular comic cycle Kajko and Kokosz about the adventures of two friends living in a fictional mid-century era. Jerzy Wróblewski created many science fiction, criminal and western stories. Bohdan Butenko wrote the children’s strip Gapiszon (Woolgatherer), while Andrzej Mleczko produced the satirical Adventures of a Cheerful Garbageman, and Zbigniew Lengren offered cultural commentary in Filutek (Little Rogue).

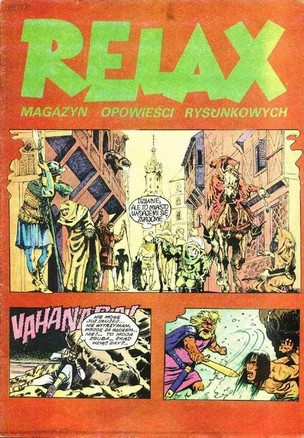

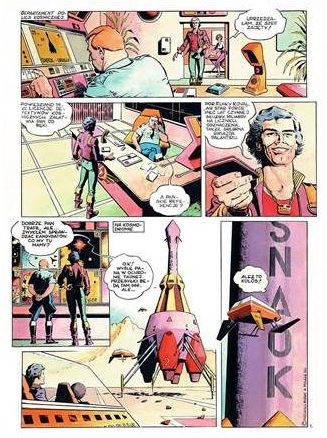

In the second half of the 1970s science fiction dominated Polish comics. The magazines Relax and Alfa both launched, announced as monthlies, although published rather irregularly. They presented historical, criminal, humor and science fiction comics made by Polish artists, but also imported works from Czech and Hungary. The current bestseller Thorgal debuted in Relax. The monthly magazine Fantastyka, launched in 1982, was dedicated to science fiction literature but dealt with all of pop culture. A few publishers started their own series. Fantastyka introduced Bogusław Polch’s Funky Koval, adding gore, politics, and sex to Polish comics. Zbigniew Kasprzak also began his career with science fiction; today he draws for the French market (e.g. Halloween Blues, Hans).

The market expanded despite the constraints of censorship, the lack of funding for foreign licenses, and the poor quality of print. Nevertheless, the 1970s and 1980s saw the appearance of a large group of artists and young fans. It was from the ranks of these fans that today’s comics publishers, critics, and journalists come.

The end of the 1980s brought an economic crash. The Communist government could not supply its citizens with enough toilet paper, let alone paper for comics. Strips were printed in dreadful quality or discontinued. Fortunately that government met its deserved end.

CONTINUE TO PART 2

Tomasz Kołodziejczak is a writer, publisher, and promoter of culture. Since making his debut in 1985, he has published six novels and dozens of short stories, in addition to creating comics and board games, and writing computer game scenarios. He is considered to be one of the most important authors of Polish fantasy, and his writings have been translated into English, Czech, Lithuanian, Russian, and Ukrainian. Since 1995 he has been working for the publishing house Egmont Poland.

Header image: Funky Koval © Bogusław Polch, Maciej Parowski & Jacek Rodek