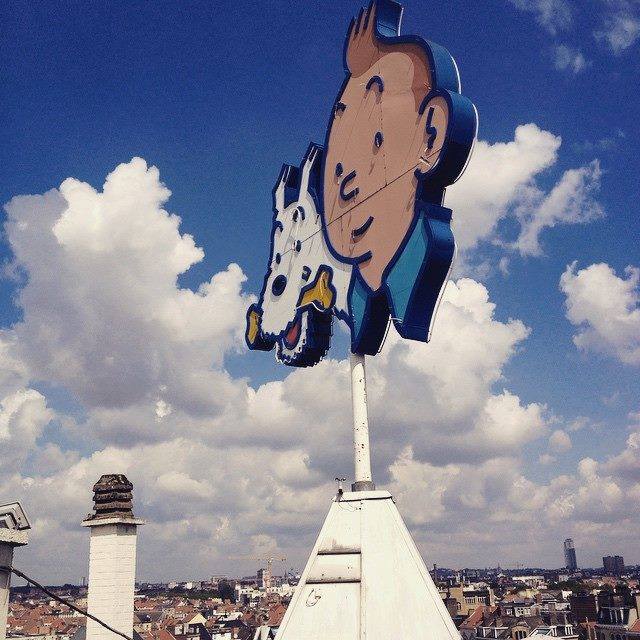

1929: The year of Tarzan, Buck Rogers, Popeye and… Tintin

At the time, European comic strips bore no comparison with American output. The enormous craze for this new medium in America escaped no one’s attention. However, it would take years for the first major Belgian comic strip to leave its mark on the evolution of comic strips.

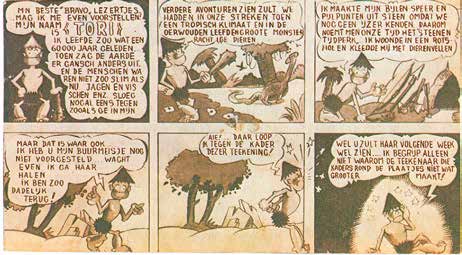

In this respect, the year 1929 was without doubt a turning point. In the US, heroes like Tarzan, Buck Rogers and Popeye made their first appearance, tapping into the readers’ craving for escapism in the aftermath of the stock exchange collapse. In Europe, Georges Remi, aka R.G. or Hergé, burst on the scene with a ginger-haired reporter called Tintin. The adventurous hero was inspired by a similar character Hergé had created during his military service, whose adventures were published on a two-page spread for three years, from 1926 to 1929, in the Catholic boy scout magazine Le Boy-Scout. His name: Totor, leader of the Garden Beetle patrol. Totor’s formula was straightforward: cartoons with subtitles, and the occasional speech balloon. “In the beginning, I was making comic strips without knowing it,” said Hergé in a 1978 interview. “I thought I was just telling stories with images.”

Tintin’s first story was published in January 1929: The Adventures of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (Les Aventures de Tintin au pays des Soviets) in the pages of the Petit Vingtième, a children’s supplement to the Belgian conservative Catholic newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle. With this story, Hergé veered away from the humorous style in vogue in Europe at the time, and opted for a more American kind of adventure. This decision was highly influenced by Hergé’s editor-in-chief, the ultra-conservative Norbert Wallez, who also happened to be a journalist, a priest and an admirer of the Italian dictator Mussolini, a detail not without significance. The heads of the Catholic press were ecstatic; they were winning on both fronts! The album clearly hammered into the young readers’ little minds that Russians were ruthless communists.

The story followed the travels of Tintin, an intrepid young reporter for Petit Vingtième, across the Soviet Union. The titular hero did not yet sport his characteristic quiff. His feet looked like two loaves of bread that hadn’t properly risen, his body was squat and he looked much younger. The sense of detail and credibility, which would become Hergé’s trademark, was totally absent. The thought bubbles were non-existent: the faithful Snowy talked to his master in speech bubbles!

As for the story, Hergé dug into a book entitled Moscou sans voiles (Moscow Unmasked), by the former Belgian Consul Joseph Douillet. The book was nothing more than a typical example of that era’s propaganda, and as a result so was the first of Tintin’s adventures, in which Hergé, fierce opponent of the Russian regime in place, drew a crude caricature of that unknown and faraway country. Even though the author would later describe that story as a “sin of his youth,” Tintin experienced a tremendous overnight success, in levels comparable to The Yellow Kid or Little Nemo a few decades earlier in the US. When the pages depicting his return from Moscow were released, a huge celebration was even held at the Brussels Gare du Nord train station to welcome the hero. This first publicity stunt for a comic strip was an outstanding success. The subsequent adventures of the young ginger-haired reporter and the faithful Snowy continued to meet with the same success. Overnight, Georges Remi had become a star. His drawing style, which would become known as “ligne claire” set a trend that would be followed and imitated by many other artists.

Under the American influence

The year of Tintin’s first appearance, Paul Winckler founded the Opera Mundi press agency, with the intention of representing King Features in Europe. At the time, King Features was the biggest comic strip industry syndicate in the United States. In 1934, Winckler decided to launch a comic strip magazine, mainly to influence French newspapers, who were still reticent about US comics. The first issue of the magazine, entitled Le Journal de Mickey (Mickey’s Journal), consisted of only four color pages and four black and white ones. It featured famous American comics like Mickey, Jungle Jim and Flash Gordon, to which Winckler had acquired the rights for a dime. This strategy obviously had dire consequences. While France saw record-breaking comic strip sales in the second half of the 1930’s, the low price of American comics left little room for local authors, who had become too expensive for publication. The idea of producing comic strips locally was almost abandoned. In this context, the influence and hold of American comic strips over European magazines kept growing stronger.

The weekly Dutch magazine Bravo! was first launched in 1936, followed four years later by its French version. At the beginning, the magazines published American comics almost exclusively, comics such as Felix the Cat, Flash Gordon (or Guy l’éclair as he was then known in French), Dikkie en Dunnie and The Katzenjammer Kids. Local comic strip artists would join later on, notably Vandersteen (Tori, Sinbad the Sailor), Rob-Vel (Toto), Paul Cuvelier (under the pen-name Sigto) and Albert Uderzo (Captain Marvel Junior). 1938 also witnessed the birth of the twin magazines Spirou (in French) and Robbedoes (in Dutch), which initially published many American series, including Superman, Tex, Red Ryder and Dick Tracy. The same course was taken by the Dutch magazines Ons Kinderland and Wonderland, which first came out in 1937.

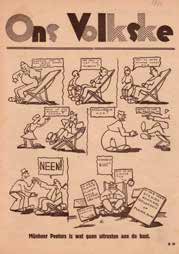

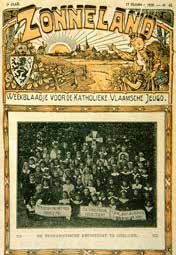

And yet, hope was on the horizon. In Flanders, the monks running Averbode publications fell under the discreet charm of conservative bourgeois morals, championed by Tintin in his early days. The growing success of other magazines dedicated to “proper” youth, such as Ons Kinderland and Ons Volkske, swept away whatever misgivings they had. Between 1930 and 1940, the monks published more and more comic strips in Zonneland, their educational brochure for children in their fifth and sixth year of primary school.

In 1934, Averbode published a serial story running over several issues for the first time. While modern readers would be puzzled by the edifying titles of the series, older generations still get misty-eyed at the mention of Rommelzak et Fokkie, Kinderlijke heldenmoed (Childhood Heroism) and Avonturen van Profje en Struisje (The Adventures of Profje and Struisje).

The monks had so much faith in the strength of the medium that, even during the war, no less than three albums in French came off their printing presses! Alongside Jijé, they published artists like the Flemish Jan Waterschoot and the Breton Gervy. Eventually, Jijé—by then the second most famous Belgian comic artist after Hergé—left Averbode to join a new magazine from Charleroi called Spirou, taking with him his series Blondin et Cirage (Blondie and Shoeshine).

The first album with speech balloons was published by Petits Belges in January 1931. Evany (Eugène Van Nyverseel), Hergé’s first assistant at Le Petit Vingtième, published Zim et Boum, a story not unlike Tintin but which ended after only 52 pages. Evany never was one for long story arcs.

In 1936, Jijé made his debut with Le Dévouement de Jojo (Jojo’s Dedication), in the pages of La Semaine du Croisé (The Crusader’s Week), the main competitor of Petits Belges. It would become the first episode of his first album. Jijé was the first Belgian comic strip artist capable of keeping up with Hergé. Jojo became a big success for Le Croisé. Two adventures were released before the war intervened on May 5th 1945, interrupting the publication of the third adventure, Freddy aux Indes (Freddy in India, as Jo-Jo was now known).

In 1939, Jijé was everywhere. Freddy was published in Le Croisé, and made an appearance in issue 17 of Spirou, in a story called La Clef hindoue (The Hindu Key). After that, Le Journal de Spirou published Trinet et Trinette dans l’Himalaya (Trinet and Trinette in the Himalayas), followed by a short episode of Spirou, which Jijé had to take over as Rob-Vel was not available.

In that period, Jijé could also be seen in the pages of Petits Belges with his heroes Blondin and Cirage, where they went on three adventures from July 1939 until September 1942. Blondin et Cirage is the story of two seemingly inseparable boys—one white, the other black. The series was deeply imbued with Christian charity and the Catholic faith in general, which was still very powerful at the time. The priests could rejoice: their comic strips were very edifying! Hallelujah!

Blondin et Cirage did not appear in Zonneland, the Dutch counterpart of Petits Belges. The content of the two publications were very different. After the war, though, the adventures of Blondin et Cirage were collected in an album in Dutch entitled Wietje en Krol. In 1947, Spirou would re-launch the series, first penned by Hubinon, who would hand it back to Jijé in 1951. Wietje en Krol would continue to be published in the pages of Robbedoes under the title Blondie en Blinkie.

1939 was an important year. Jijé brought his two curly-haired little troublemakers with him to Spirou and developed his style, a versatile mix of comedy and caricature, which would become the distinctive trait of the weekly magazine and go on to influence many comic strip artists.

Meanwhile, in the French-speaking part of Belgium, most artists weren’t faring well. But, as the saying goes, every cloud has its silver lining. World War II reshuffled the deck by limiting, if not stopping, all American imports of comics. Many comic strip authors, including Jacques Laudy, Jijé, Sirius and E.P. Jacobs, jumped on the opportunity and flooded the newspapers and magazines with their own productions. E.P. Jacobs was even invited to replace the American master Alex Raymond and pen a proper ending to the adventures of Flash Gordon, which were so brutally interrupted. He would eventually use this experience to create Le Rayon U (The U-Ray), which would in turn inspire him to create his masterpiece: Blake and Mortimer (Blake et Mortimer).

“We didn’t know what we were doing.”

To say that the first Belgian comic strips were inspired by US series would be putting it (very) mildly. A quick look at the evolution of comic strips provides adequate proof of this. In fact, while some authors were merely influenced by their American counterparts, others were going as far as plagiarizing them.

In 1928, journalist Léon Degrelle, stationed in Mexico at the time, regularly sent Spanish-language newspapers to the editors of Le Petit Vingtième, where Hergé was working. For Tintin’s creator, it was an opportunity to discover the comic strips published there, most of which were American: The Katzenjammer Kids, Krazy Kat, and George McManus’s Bringing Up Father. Hergé soaked in McManus’s “talent, virtuosity and humor.” Years later, he would eventually admit that he had been subconsciously inspired by McManus’s characters’ round noses, specifically their pert and delicate shape, for his own creations. By the same token, the subconscious might also be to blame for Hergé outright borrowing characters from that series, and putting them to use in Tintin. Franquin was another artist to find inspiration across the pond. He was a huge fan of Blondie (Chic Young), The Katzenjammer Kids (Rudolph Dirks), as well as Disney’s creations, such as Mickey, Popeye (Segar), Bringing Up Father (McManus), and particularly Martin Branner’s Winnie Winkle. Some scholars found traces of the latter in Modeste et Pompon, a series launched by Franquin a few years later. Flemish author Buth also borrowed from Chic Young’s Blondie, Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant and Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon as well. The latter’s influence on Buth is nowhere more evident than in his 1943 series Gawain, de dappere (Gawain, the Brave).

But for some authors it went much further than mere inspiration. In the 1940’s and 50’s, Belgian authors Sirius, Jan Waterschoot and, most of all, Willy Vandersteen produced shameless copies of Prince Valiant, Hal Foster’s Arthurian classic. In his outstanding work Prins Valiants zwartboek over plagiaat (Prince Valiant: The Black Book of Plagiarism), Dutch painter Rob Möhlmann, a Hal Foster aficionado, noted far too many coincidences to pass as mere flukes. For instance, in his illustrated biography of Godfrey of Bouillon (1948), Sirius, creator of the famous Timour series, reproduced time and again points of view and angles taken straight out of Prince Valiant. The series also served as a model for illustrator and cartoonist John Waterschoot in the eponymous album recounting the adventures of the warrior monk Willem van Saeftingen, published in 1953 in Kerkelijke leven (Religious Lives). Nine years later, Waterschoot went even further, merging two sections taken from Foster’s medieval series for his own Quinten Matsijs.

Continue to Part 3

From La Belgique dessinée by Geert De Weyer

Translated from the French by Storyline Creatives