Forgotten, neglected, and caricatured, women long held secondary roles in the highly masculine world of comics. But those days are over, thanks to figures like Wonder Woman and Mary Jane Watson, Laureline and Marji, Lucy Heartfilia and Lady Snowblood. Whether adventurers or lady loves, femmes fatales or free spirits, these bold heroines now count among the most striking and significant characters of the ninth art. Here are some of them and their stories.

CALAMITY JANE

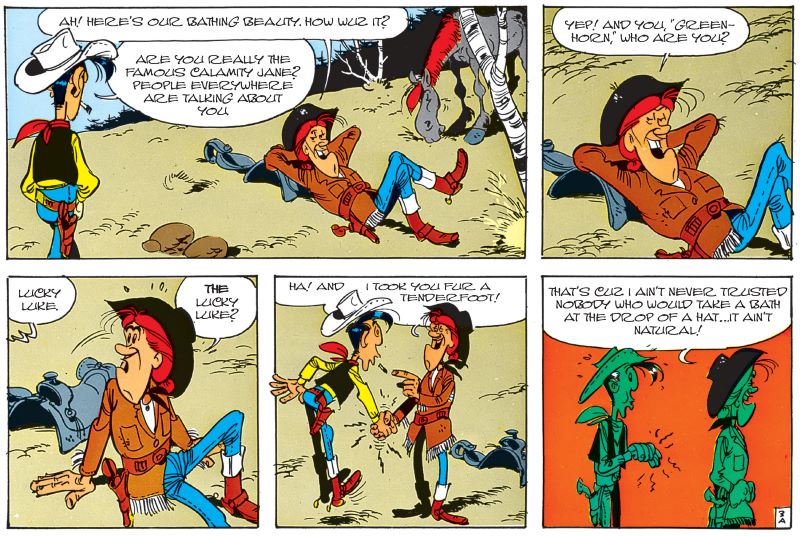

René Goscinny (writer) and Morris (artist), Lucky Luke (1965), Cinebook – Originally published in French by Dupuis

The crazy squaw

The first time the Apaches crossed paths with her, they beat a hasty retreat, terrified by the “crazy squaw.” You can’t blame them: nobody wants to find themselves at the business end of her shotgun. These proud warriors are known to be fearless, but she’s no ordinary woman. Inspired by the adventurer Martha Canary Jane, Calamity Jane dresses like a man and is a better shot than most cowboys. She spits tobacco, she’s foul-mouthed and she’s not too fond of washing: “I ain’t never trusted nobody who would take a bath just like that… It ain’t natural!” she says upon meeting the freshly-bathed Lucky Luke, giving him a bone-crushing handshake. And you better remove your hat when she’s around, because this lady will gladly pull out her gun to teach you some manners. As a young child, she played rodeo on a real-life cow… or so she says. It’s hard to draw the line between fact and fiction with her. “I’m also a great liar, but wait, I haven’t finished yet,” she tells Lucky Luke, halfway through her spectacular life story.

True colors shine through

Calamity Jane had already appeared twice in the adventures of the lonesome cowboy: on a wanted poster in The Outlaws and as a member of Jamon’s gang in Lucky Luke versus Joss Jamon. But these versions were a far cry from the lantern-jawed, tobacco-chewing redhead in the album named after her. Morris and Goscinny’s Calamity Jane is a woman at a crossroads, torn between her taste for adventure and the desire to settle down. “Say—I’d like to find myself a quiet little place and live a normal life,” she tells Luke, just before spitting out her chaw (old habits die hard). She’ll go so far as to take etiquette lessons, taught by a doppelganger of British actor David Niven, who’ll end up losing his cool and heading back out East, swearing like a devil. As for Calamity Jane, she realizes she’s “not made for settling down” and goes back to her old life, roaming free, heedless of the social constraints that burdened women of the 19th century out West. Alongside Calamity, the real American frontier woman Martha Cannary has also been the subject of a beautiful graphic novel, created by Christian Perrissin and Matthieu Blanchin (Futuropolis).

PÉLISSE

Serge Le Tendre (writer) and Régis Loisel (artist), The Quest for the Time Bird (La Quête de l’oiseau du temps – 1975), Titan – Originally published in French by Dargaud

Daughter of the princess-sorceress

Pélisse’s destiny is both tragic and glorious. Tragic, because of what happens to her—spoiler alert—in the final volume of The Quest for the Time-Bird, a series that launched the French heroic fantasy trend. Glorious, because of the lasting impression she left on readers of the Quest. It all began in the Marsh of Veils, where a young woman with thick red hair decided to undertake the most dangerous quest on Akbar: to seek out the mythical time-bird. The woman is Pélisse, daughter of Princess-Sorceress Mara. One of the villainous gods of Akbar, Ramor, is imprisoned inside a conch, but the magic that keeps him inside has weakened, threatening to unleash death and destruction upon the world. Sorceress Mara has found a way to prevent this fate: an incantation to be pronounced before the “night of the changing season.” In order to achieve this, however, she needs a mythical bird that has the power to control time…

Illusory and iconic

Pélisse’s encounter with Bragon, a tired old knight and her mother’s former lover, is tense and dramatic, two generations facing off. How are the two characters related? Is he her father? Bragon’s recollections of his relationship with Mara are steeped in nostalgia, and he’s convinced that the girl is his daughter. Like him, she’s impulsive, and like her mother, she’s free-spirited… She’s also brave, she needs to have the last word and—where necessary—she can be lethal. Bragon likes everything he sees in her and eventually softens up to her moral “qualities.” In an interview, scriptwriter Serge Le Tendre once explained: “It’s her disposition that makes her so likeable. She’s sort of child-like, wily and mysterious. Pélisse has it all: a body that men never tire of admiring, and the wits to go with it. She’s an icon.” One that leaves her mark on Bragon as much as readers of The Quest for the Time-Bird.

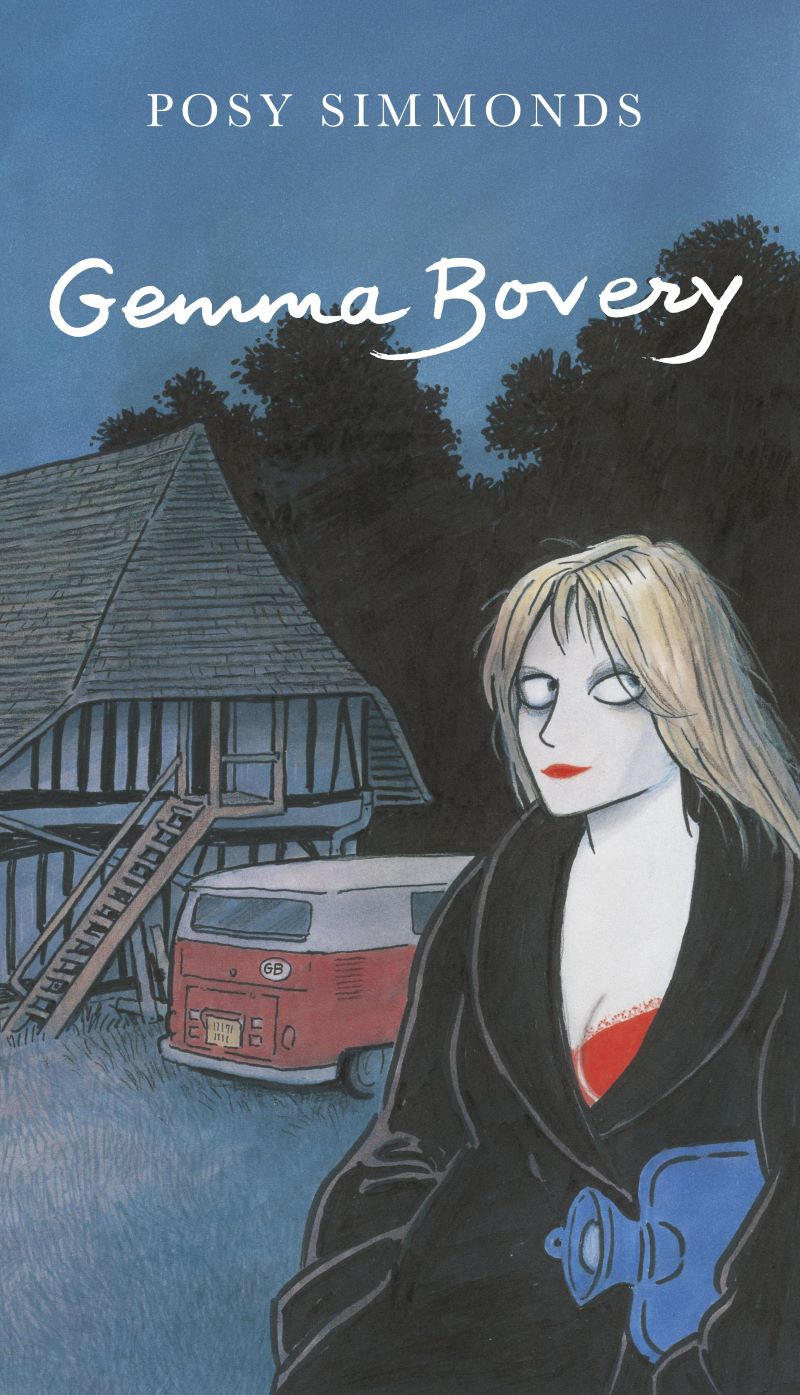

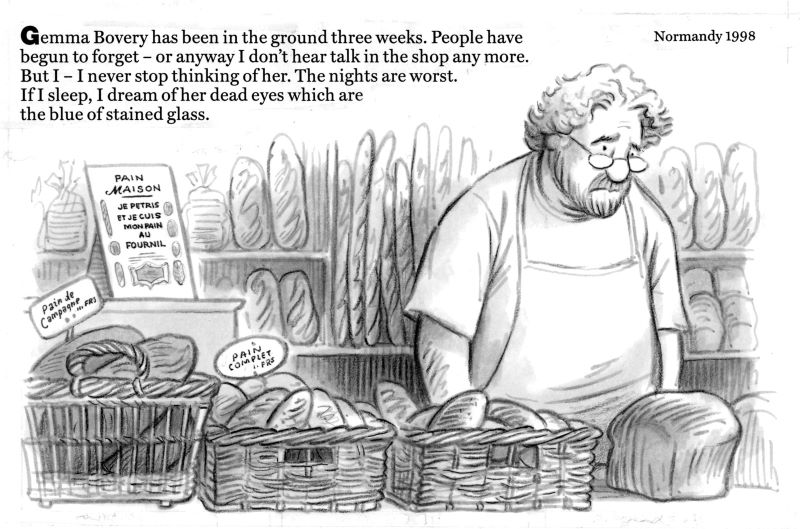

GEMMA BOVERY

Posy Simmonds (writer and artist), Gemma Bovery (1997), Jonathan Cape publishing

Madame Bovery

This graphic novel draws parallels with Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. Whether Gustave would have enjoyed reading Gemma Bovery, we’ll never know… One thing is for sure, French readers are far more likely to pick up this delectable story by Posy Simmonds than to relive the painful memories of compulsory readings in school by revisiting Flaubert’s most famous book. Gemma Bovery is very much a bored housewife, just what every husband wants… Her boredom leads to a plethora of absurd situations. A former London socialite and victim of a love story that never really took off, Gemma cozies up to a furniture restorer and turns into a dowdy housewife. Her other half, Charlie, is a bland, divorced dad. His two kids, his cranky ex-wife and the terrible neighborhood he lives in drive Gemma to her limit. Eventually she has enough, and decides to drag Charlie to a place where “culture and style go hand in hand,” a place where “the food isn’t full of chemicals.” In short, Gemma is heading for France. More accurately, she heads for Normandy, to settle in a village called, ironically, Bailleville (“Yawntown” in English). The initial excitement soon gives way to fewer ups and more downs, to infidelities and reconciliations, just like in Madame Bovary.

Emma and Gemma

The book begins with her death, so we know from the outset that Gemma’s story doesn’t end well. The story is told alternately through her diary entries and the recollections of Raymond Joubert, the local baker. Joubert has fled the highbrow social circles of Paris and come to take over the family business. He is crazy in love with Emma, going as far as secretly influencing her life for fear of her meeting the same tragic fate as Flaubert’s Emma Bovary. However, Gemma’s not Emma: she might be in over her head, but she’s definitely not suicidal. Posy Simmonds seamlessly combines classic fiction and sequential art in a story that just flows. Gemma starts off a bit annoying, but she becomes more and more likeable as the tale goes on. By the end, the reader feels her end is unduly tragic. What would have been a light-hearted story is sobered considerably by the main character’s disappearance. As for Joubert, his overly literary concerns are trumped by a series of exhilarating revelations told with malicious glee.

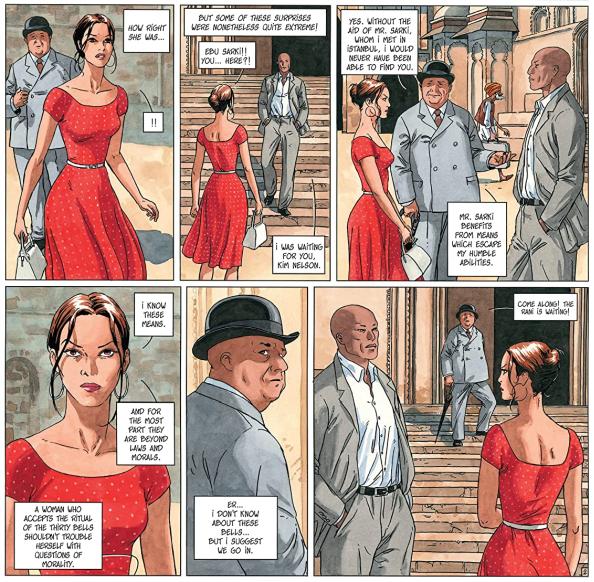

KIM NELSON

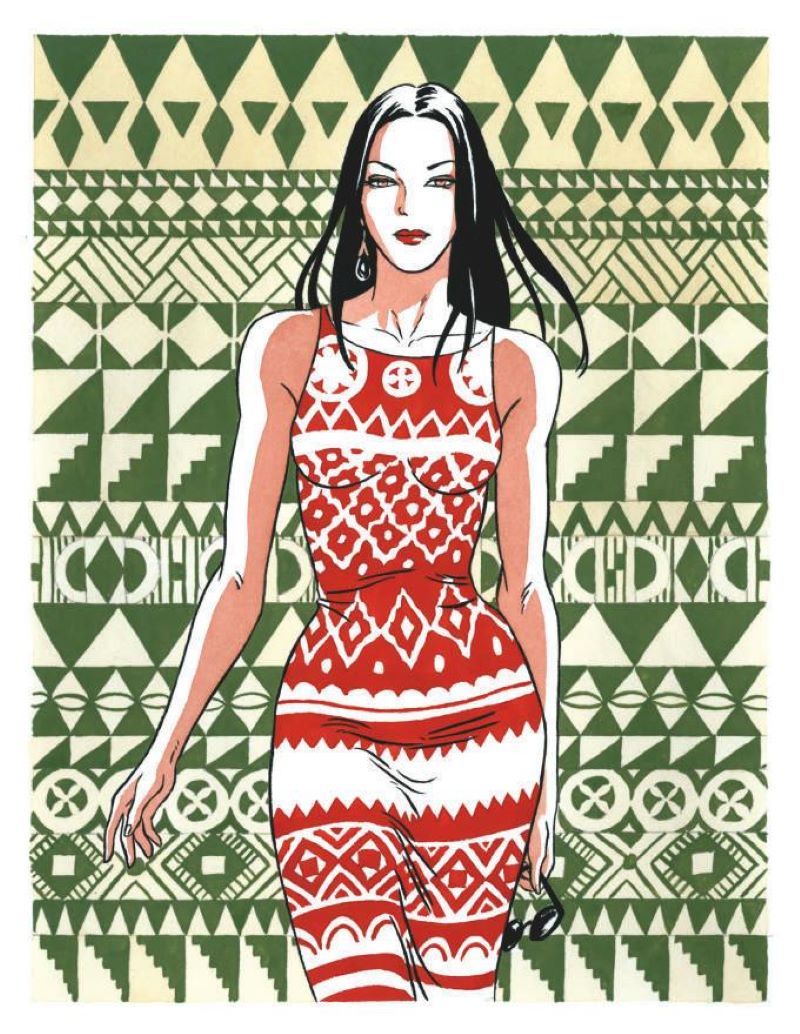

Jean Dufaux (writer) and Ana Mirallès (artist), Djinn, Europe Comics & Insight Editions – Originally published in French by Dargaud

“I’m looking for a Djinn”

The story begins in Istanbul, where a young woman named Kim Nelson is searching for information on her grandmother, Lady Nelson. The latter had married a diplomat and traveled around the world in the 1910s, away from her stifling familial and social environment. Kim’s quest doubles as a search for the treasure hidden by Sultan Murati, which he had amassed for Germany shortly before WWI. Maybe the answers Kim is looking for lie in the city library, or in the old quarters of the city, where brothel-keeper Ms. Fazila knows someone who could help. It’s a dangerous road for Kim, as one man warns her: “You’ve thrown a stone into a still pond… The ripples are spreading… You have to deal with it now.” Along the way, she discovers that her real grandmother was actually a woman called Jade. Lady Nelson had become one of the sultan’s wives, and she found herself in a love triangle with him and this mysterious and fascinating woman called Jade, who liberated her sexually. “Are you talking about Jade? I heard she’s a djinn who bewitches men,” a British diplomat confides to Kim. “It never ends well for them…”

A supernatural and dangerous creature

Djinn constantly shifts between past and present, setting the scene in both contemporary and Ottoman Turkey. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire still played a major role in international politics, led by a sultan who would be the last of a long line of rulers before being toppled by the Young Turks and their leader, Enver Pasha. Djinn tells the story of Kim and Jade, two women separated by time but linked by blood. Kim is unable to move forward until she fully understands her past. She will gradually uncover the heavy secret and the true nature of her relationship to Jade. As a djinn, a supernatural and dangerous creature, Jade’s spirit will come to take hold of Kim. Djinns cannot feel, which forces Kim to repress her love for Ibram Malek, a charming young man who has been helping her since her arrival in Istanbul. As Ms. Fazila tells Ibram, “Soon her heart will be empty. Don’t fall in love with a djinn.” Kim is doomed to a life of solitude. She bids Ibram farewell before leaving for Africa to retrace Jade’s steps. “If I stay, sooner or later I’ll end up hurting you… And you wouldn’t stand a chance against a djinn… Nobody can…”

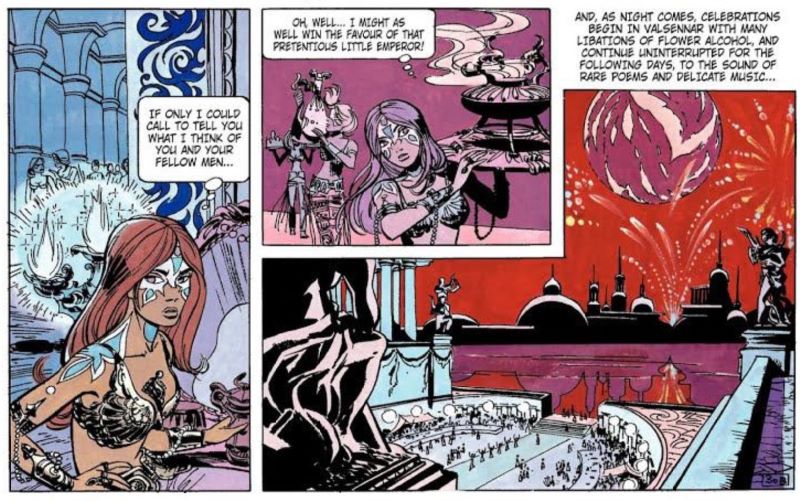

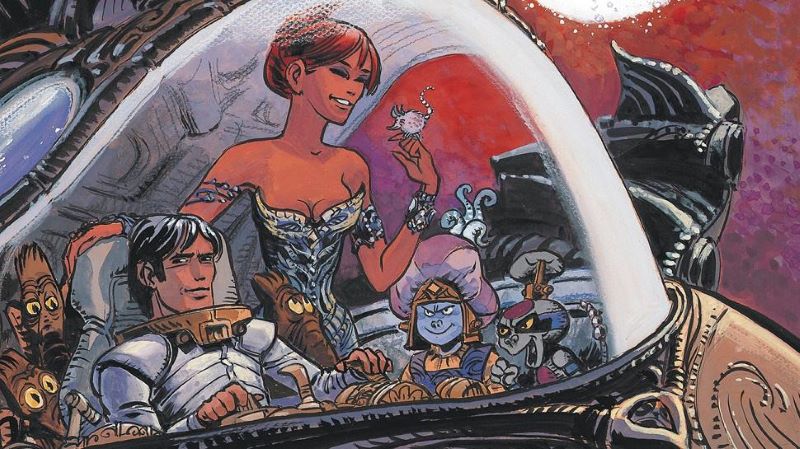

LAURELINE

Pierre Christin (writer) and Jean-Claude Mézières (artist), Valerian & Laureline (1967), Cinebook – Originally published in French by Dargaud

What kind of heroine is likely to emerge from the mind of a scriptwriter who reads Simone de Beauvoir and supports feminist ideas? Unsurprisingly, one that’s radically different from traditional female characters. While Valerian headlines the couple’s adventures through space and time, Laureline has always been the backbone: a modern and astute young woman with a sense of humor and sharp critical thinking skills. Pierre Christin probably had a bit of a crush on her…

Young and wild (and free)

Laureline owes a lot to the fans of Pilote. Fans flooded the weekly magazine with requests to promote her to a fully-fledged member of the Valerian Galaxity universe, making her one of the first heroines to grace the world of French comic books. She also owes a fair share of her success to American feminism, which left an impression on Pierre Christin following his visit to the US in the 1960s. This trip inspired him to create a female character with strong, original characteristics, doing away with what he called the “comic book masculinity” that only favored male heroes. Laureline originally appeared in Christin’s dreams. He shared these with his daughter, describing his visions of a “beautiful young woman in the forest.” This is exactly how Laureline appears to Valerian in the first episode of Bad Dreams. While on a mission in the Middle Ages, Valerian falls asleep and is snatched up by a giant plant. Here comes Laureline, a young and incredibly sexy wildling who saves him and offers to be his guide. This scene offers telling insight into the character’s artfulness and her role alongside Valerian.

Barbarella and Simone de Beauvoir

When Christin and Mézières created the Laureline and Valerian saga in 1967, at a time when science fiction was a fledgling genre in France, they didn’t expect it to be going strong four decades on. Female leads were few and far in between. Some stories did put women in the lead of course, like Les Pionniers de l’Espérance by Lécureux and Poïvet, or Barbarella by Forest, but these didn’t do much for Christin. For inspiration, he turned to The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir, and the American science fiction genre: in particular, Poul Anderson’s Guardians of Time.

An ideal woman

Laureline and Valerian are spatio-temporal agents who travel through space and time. Their story faithfully reflected Pierre Christin’s generous and inquisitive view of the world, backed by a creative and original artist who perfectly translated Christin’s ideas into images. Christin consistently chose topics for his stories that may seem ordinary today, but were actually controversial at the time: the threat of nuclear war, the state of the environment, the risks of globalization, inter-ethnic violence, the end of utopian ideals and the power of new media. What made him a true pioneer was his handing the leading role to a woman. Following his return from the US, where he saw widespread feminism, he made Laureline “modern and resourceful”. Christin explained: “To me, the ideal woman was educated, athletic and professionally active, like the women I had seen at the Sorbonne. She definitely couldn’t be a bimbo, and Jean-Claude Mézières did a great job at avoiding that. Laureline is my favorite character: we are like-minded, her lines come so easily to me.”

Subversive

The differences between Laureline and Valerian quickly become clear. Valerian has a taste for action, a sense of duty and a tendency to blindly follow orders, rushing headlong into the unknown. “Always following orders, right?” Laureline tells him in Welcome to Alflolol, as he’s about to take on a dubious mission. She’s the one with perspective, although that causes some to call her “subversive.” “Laureline comes into her own,” says Christin “She portrays a mix of morality, humor, and efficiency; she’s a carefree character and her beliefs are more progressive than Valerian’s. He walks the line, closer to the military world, and isn’t as smart or as eloquent as her. She is constantly looking for alternatives, with the least collateral damage. She’s open to psychology and the extra-terrestrial species to whom she reaches out. I believe she’s the real hero in this story.”

And yet, it took twenty-one episodes for her to make it on the cover; it finally happens in the penultimate episode of the series, The Order of the Stones, where “Valerian the spatio-temporal agent” becomes “Valerian and Laureline.” We can suppose that Laureline was humble enough to let Valerian get all the credit, and smart enough to let him think he was in charge…

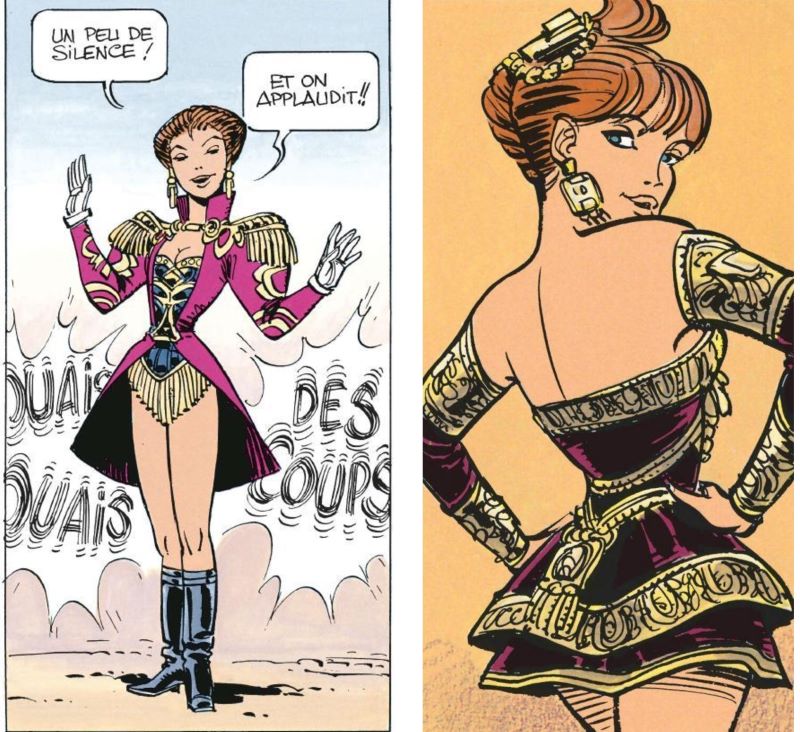

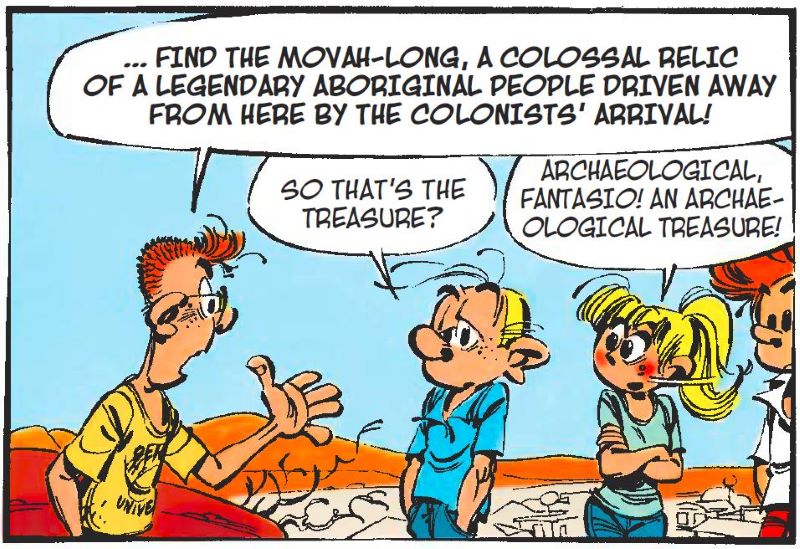

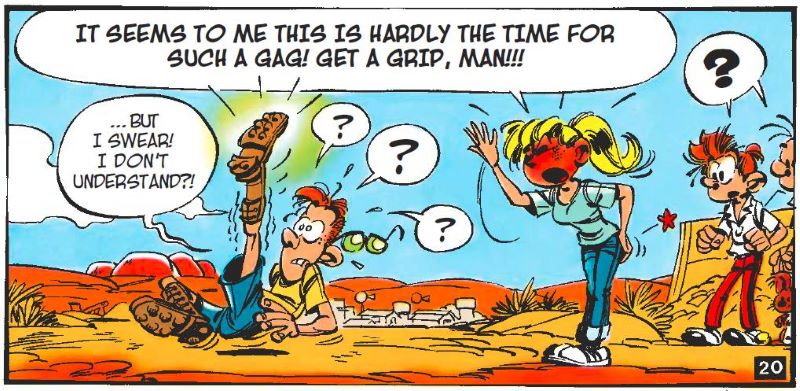

SECCOTINE

André Franquin (writer and artist), Spirou & Fantasio (1952), Cinebook – Originally published in French by Dupuis

She might share a name with a brand of glue, but she’s not getting stuck on anyone. Seccotine is a journalist with a talent for breaking news. Feisty, sharp and charming, she’s a woman ahead of her time. Modern and free-spirited, Seccotine stands in contrast to the rest of the well-behaved comics heroines of the 1950s.

No women allowed!

Some say art flourishes when constrained. One of the heftier restrictions on French and Belgian comic book writers in the 1950s can be summed up in just three words: no women allowed! Maybe the odd inoffensive housewife was tolerated every now and then. Including an attractive woman would be troubling enough for young male readers; having her play a leading role was simply out of the question, as it would shake the foundations of male-hero supremacy. “You know, there weren’t a lot of women in comic books back then. Hergé and myself grew up at a time when schools weren’t mixed. Newspaper editors followed the moral values set out by a Catholic education system,” André Franquin explained in a 1996 interview. The combined threats of restrictive French legislation—passed on July 16, 1949 to increase control over youth publications—and pressure from editors pushed writers to censor themselves and exclude female characters from their stories. Scriptwriter Maurice Rosy (Tif & Tondu) elaborated on the topic: “Female characters in [weekly comics magazine] Spirou were few and far between mainly because we never really knew how far we could take them. So we simply left them out.”

I’m a journalist, you fool!

Seccotine first appeared in The Rhinoceros’ Horn, a remarkable feat at a time when female characters were considered “a dangerous idea,” according to Franquin. Like Fantasio, Seccotine is a journalist for Le Moustique weekly. Young, resourceful, witty, sharp and full of energy, she lives her life the same way she rides her scooter: at full speed. But her greatest quality is her persistence—crucial for any good journalist—which she puts to good use throughout her adventures. She’ll sometimes even be a step ahead of Fantasio, who never passes up a chance to patronize her (with little success).

There isn’t a single ounce of chemistry between the two characters. They keep it professional. In the final scene of The Rhinoceros’ Horn, Seccotine demonstrates her talents: while pretending to powder her nose, her concealed camera captures the prototype of the Turbotraction car, the so-called “road queen” whose stolen plans they had recovered. It took Spirou’s wits to finally reveal the ruse Fantasio fell for.

Seccotine the fashion victim

She starred again in The Dictator and the Mushroom, and played the main role in The Marsupilamis’ Nest, where her story on the private lives of Marsupilamis will steal the show, taking the spotlight away from Spirou and Fantasio. Seccotine will eventually be erased by Franquin, who was stumped after young female readers kept complaining that her clothes were dowdy. He spent hours flipping through fashion magazines to find “trendy” outfits for her, but finally decided to simply cast her aside. However, in the stories where she appears, Seccotine looks stylish and attractive in her short jacket, headband and high-heeled plaited sandals.

Timeless

After Franquin, others come along to try to breathe new life into Seccotine. In Tome and Janry’s 1998 Machine qui rêve, readers see her flirt with Spirou. In Yann and Tarin’s 2007 Le tombeau des Champignac, she playfully asks him if he’s ever kissed a girl. While these changes stray pretty far from the original characterization of Seccotine, they can’t be considered altogether transgressive, given the way comic books have evolved. The story’s real novelty is in how Franquin managed to create a timeless heroine, who hasn’t lost her relevance or allure sixty years after her debut.

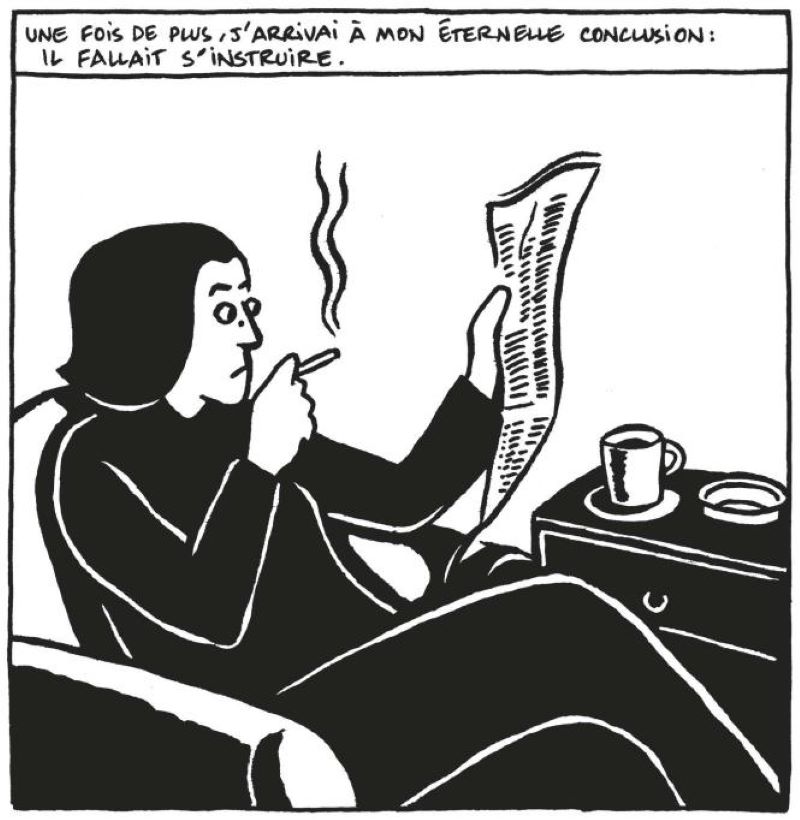

MARJI

Marjane Satrapi (writer and artist), Persepolis (2000), Pantheon – Originally published in French by L’Association

God, Marx and Marji

When she was a young girl, Marji dreamed of becoming a prophet. Her bedtime was often held up by her lengthy conversations with God. Eventually, Marji discovered a bearded man named Karl Marx who bore a striking resemblance, but was “a tad curlier.” She became fascinated by a comic book called Dialectical Materialism and wanted to know everything about revolutions happening across the world, Palestinian children, Fidel Castro and her country’s own revolutionary figures. She couldn’t understand why the maid wasn’t allowed to sit at their table and felt embarrassed riding in her dad’s Cadillac. The thing is, several members of her family were jailed heroes, so Marji felt compelled to follow in their footsteps. When the Iranian revolutionaries who had been in power since 1979 executed her uncle Anouche, Marji put an immediate end to her friendship with God: “Shut up and get out of my life!!! I don’t want to see you again!” And right at that moment, a war broke out with Iraq.

A wonderful appetite for life

“Marji” is short for Marjane Satrapi, the author of Persepolis, which tells the story of Marji’s childhood and teenage years in a well-off, progressive family in Iran during the Islamic Revolution and the war with neighboring Iraq. It’s also a story about a lost generation and a tribute to the victims of the Mullahs’ regime.

A surprise best-seller, the graphic novel was adapted by Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud as an animated film that won the jury prize at Cannes in 2007 and a César award the following year. Marjane arrived in France in 1994. She was 24 and wanted to dedicate herself to illustration. She shared a studio with artists such as Joann Sfar, Emile Bravo, Christophe Blain and David B., who all contributed to the rebirth of the comic book arts in the ‘90s. After hearing all about Marjane’s childhood, David B. convinced her to create a graphic novel based on her stories, using an art form she knew nothing about, one that had been totally absent in her home country.

Marjane Satrapi owes a lot to David B., the author of Epileptic, whose graphic style seeps through the pages of Persepolis with flat tints of black and white. Marjane’s younger self is a determined and likeable girl who does not tolerate injustice and who stands up against authoritarian schools and religious institutions. As a teenager she is exiled to France; upon her return to Tehran, she will feel like she’s “walking in a graveyard.” Marji is a memorable character: led by wonderful zest for life, her story is at turns comic and gripping, illustrated by ascetic artwork that keeps the reader enthralled throughout.

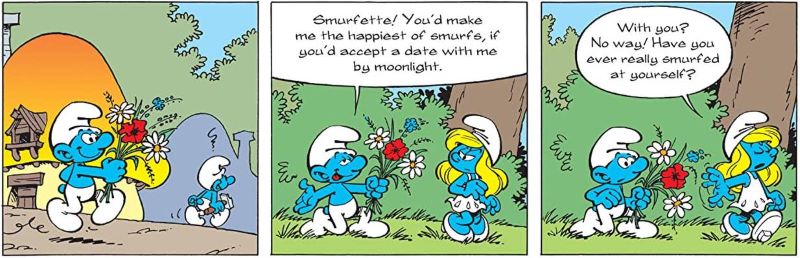

SMURFETTE

Peyo (writer and artist), The Smurfs (Les Schtroumpfs, 1959) NBM – originally published in French by Le Lombard

“They’ll go crazy over her!”

Comic books in post-war Belgium were overrun by male heroes. The Smurfs are yet another example: a community of male characters living in fear of female temptation. When their arch-nemesis, the wizard Gargamel, decides to take his revenge on the Smurfs by bringing in a woman, he underestimates the disruption this will cause in their community. “There! A real beauty! They’ll go crazy over her!” he says, admiring his creation. And how! Smurfette arrives in the village and the first question on everyone’s mind is: where will she sleep? If there’s anything the Smurfs fear more than Gargamel, it’s indecency. No Smurf dares offer to share his roof. The trouble doesn’t end there. Papa Smurf spruces her up, and the unattractive brunette turns into a gorgeous blonde Smurfette, making things even more complicated. One after another, the village-dwellers fall in love with her. Even Grouchy Smurf succumbs: you can see him secretly drawing a heart on a house. They’ve become unable to focus on work; they even paint the dam pink and start fighting over her. Gargamel definitely played his cards right!

Peyo: A misogynist?

“To send a woman into a village of a hundred guys to cause trouble!” This was Peyo’s intention, according to François Walthéry, one of his assistants at the time. Walthéry was the creator of the stewardess Natacha, another irresistibly charming female character in the world of comic books. Peyo took a risk: accusations of misogyny soon followed, which wasn’t unexpected given the magic recipe Gargamel used to create Smurfette. It goes like this: “Sugar and spice, but nothing nice… A dram of crocodile tears… A peck of bird brain… The tip of an adder’s tongue… Half a pack of lies, white, of course… The slyness of a cat… The vanity of a peacock… The chatter of a magpie… The guile of a vixen and the disposition of a shrew… And of course the hardest stone for her heart…” The bottom line: Peyo was definitely not a feminist. Even his wife was upset for weeks on end. But Peyo remained obstinate, claiming that “Smurfette is an inoffensive caricature of feminine nature, with both good and bad sides.” Smurfette ends up leaving the village after she realizes how much trouble she’s caused. But she will eventually return and become a true member of the small community. By that time, we figure Peyo’s wife had probably started talking to him again…

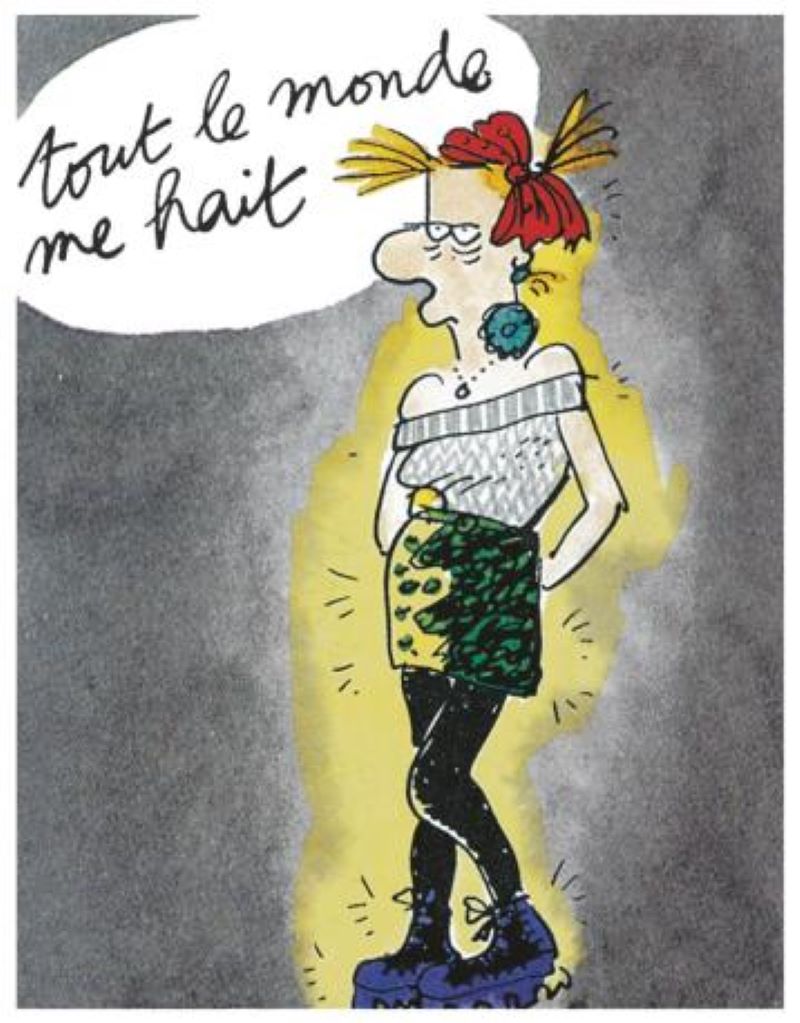

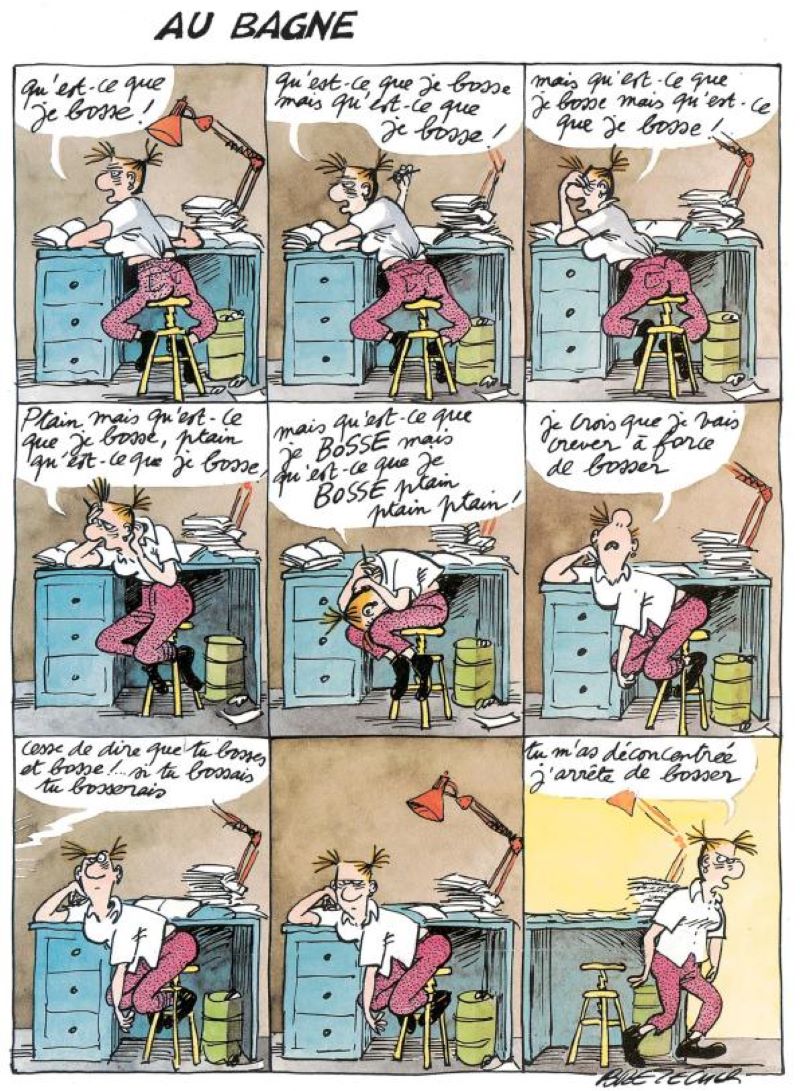

AGRIPPINE

Claire Bretécher (writer and artist), Agrippina (Agrippine, 1988), Europe Comics – Originally published in French by Dargaud

Mi drama es su drama

“Life sucks. Picasso sucks. Mozart sucks (except the music they used in that one movie). Why is everything so slimy, foul and obscene?” wonders Agrippina. For her, everything is boring, annoying, depressing, and exhausting. She’s also obsessed with existential questions, sometimes wondering how to become famous enough to “send them all to hell”—without the need to work of course. In reality, her life is going just fine. But Agrippina shares her burdensome personal drama with her friends Melfrid Potetoz, Muflée Madredios, Persil Wagonnet and Modern Mesclun (the latter is supposed to be her boyfriend, but it’s a bit complicated). As for her parents, they aren’t jobless, and they’re not crackheads either: they’re very “normal,” and her father even has a job! Papoute (daddy) writes “about real stuff,” and documents everything he can about oysters: iridescence, retracting, fibrillation and even redemption. “You think it will be a hit?” Agrippina asks Papoute. She cares about material things, but she’d never become part of the system. “I’m a creative outcast,” she says. “And these sandals were too cheap, so they’re probably knock-offs!” Yeah, life sucks.

Not angry enough

In the seventies, Claire Bretécher drew the Frustrés in the left-leaning weekly Le Nouvel Observateur, at a time when executives’ bonuses weren’t making headlines. The Frustrés were more interested in lengthy discussions (always welcome) and sitting on their cushy couches spouting pithy one-liners about their relationships, their inner selves and their love handles. Agrippina is a natural follow-up to the Frustrés, but one thing’s for sure: she’s not angry enough! Stuck in a libertarianism that constrains them from having constraints and keeps them from imposing their authority, Agrippina’s parents never say no, leaving her no option but to pretend to be part of the system she hates. She turns into a spoiled brat, a shallow rich kid. Thankfully, she’s still got freedom of speech and the incredible ability to invent words and expressions, which she uses often and to great effect. Agrippina is an annoying yet loveable young girl, too “ah-mazing” for words, but somehow a perfect reflection of her era.

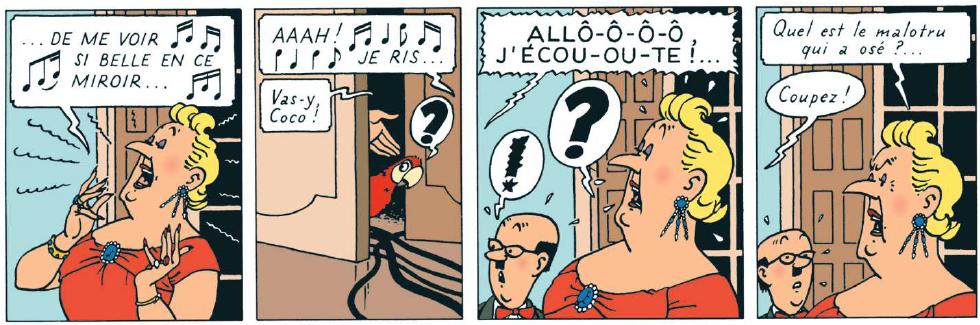

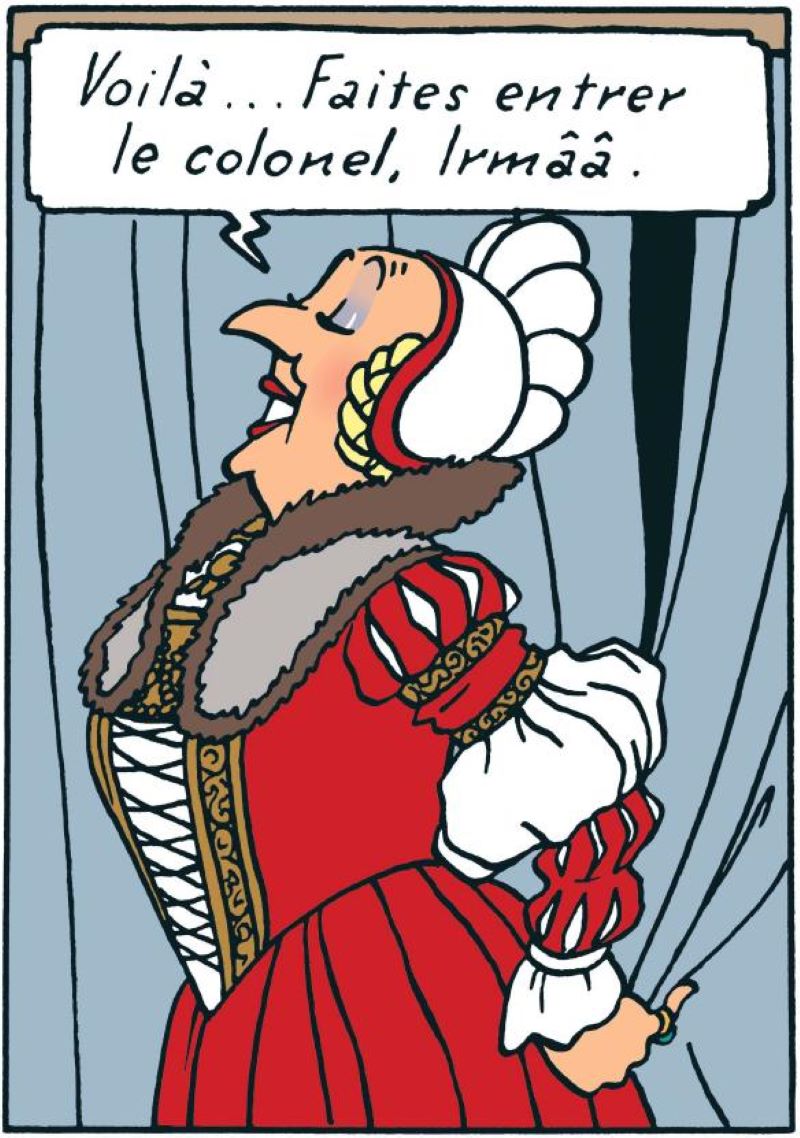

BIANCA CASTAFIORE

Hergé (writer and artist), The Adventures of Tintin (Les Aventures de Tintin; 1939), Casterman

A bit of a handful

Neither Tintin nor Captain Haddock can stand her singing voice. “I don’t know why, but whenever I hear her it reminds me of a hurricane that hit my ship when I was sailing in the West Indies some years ago,” Haddock tells Tintin in The Seven Crystal Balls. The same way Séraphin Lampion (Jolyon Wagg in English) crashes every party, Castafiore shows up uninvited at the Château de Moulinsart (Marlinspike Hall) and makes herself at home, bringing her piano, her assistant Irma, and her accompanist Igor Wagner, who “obviously has to… ha! ha! ha… accompany me.” She’s can’t ever get Captain Haddock’s name right, initially referring to him as the “deep sea fisherman” when they meet in The Red Sea Sharks. Paddock, Karbock, Kappock, Koddack, Kosack, Kolback, Kapstock or Harrock, he’ll get the whole suite of options. “Harrock’n’roll Signora Castoroili,” he snarkily replies. The rest of the characters will also have the honor of having their names butchered, from Professor Calculus to Jolyon Wagg. Castafiore is also a self-proclaimed expert in everything, asserting that the Louis XII furniture at Moulinsart is actually in the style of Henry V. And for good measure, every once in a while, she faints dead away.

Yes, but…

Her sharpness will help save Tintin and Haddock from border police chief Colonel Sponsz in The Calculus Affair. When the colonel comes into her dressing room, she hides them behind a curtain, and when he discovers Haddock’s cap left on a seat, she tells him it belongs to the tenor in Madame Butterfly. While she has a gift for mangling names, we must remember that Haddock himself stumbled when introducing himself to her: “Hoddack… er… Haddad… Excuse me, Haddock.” Castafiore defends the weak, too: when the two super detectives Dupond and Dupont (Thomson and Thompson) accuse Irma of stealing Castafiore’s jewels, the opera singer will hear nothing of it. She condemns their attack on a vulnerable woman and threatens to complain to the Human Rights League. She also stands her ground in Tintin and the Picaros, when General Tapioca accuses her of plotting against him and sentences her to life in prison: “Why, you’re ridiculous, my little soldier!” she says while powdering her nose, and goes on to sing her infamous high-pitched “Jewel Song,” wreaking havoc in the courtroom. “She’s a great lady, a real dame, and a true friend,” says Mireille Moons, who created the character. She sees this “20th century diva” as the female incarnation of Tintin creator Hergé: “Castafiore is Hergé, and without even knowing it he managed to create an archetype: there’s a Castafiore in every single one of us, singing and laughing without care.”

The Heroines of Comics: Europe is the first of a four part article series The Heroines of Comics written by Christophe Quillien and published in France as Elles : Grandes aventurières et femmes fatales et de la bande dessinée, Huginn & Muninn, 2014. The second, third and fourth parts, on the USA, Japan and Erotica, will be release later this year.

Header image: [Calamity Jane] © Morris / Lucky Comics, 1971