The Early Years

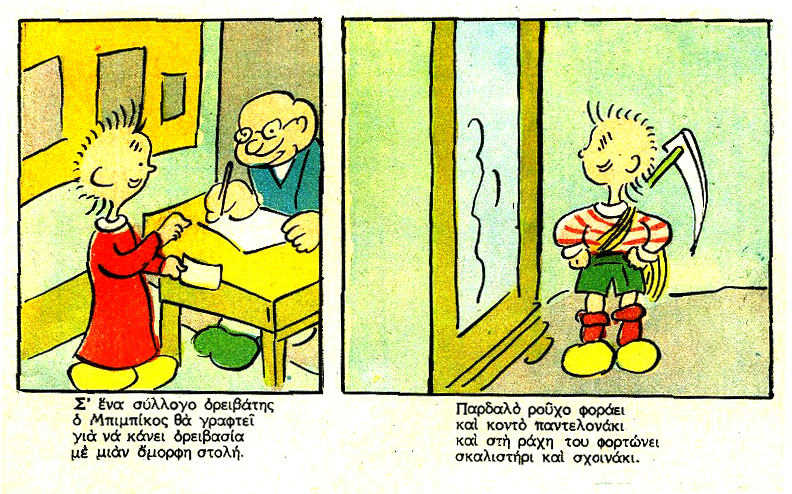

The roots of Greek Comics can be found in the early 20th century, and mainly through the interwar period, with the evolution of the satirical cartoons (mostly socio-political) in a certain “strip” form. One of the Greek pioneers of this form was sketch artist Fokion Dimitriadis with his single page strips in the newspaper Elefthero Vima, which debuted in 1927. In the next decade, this form of art will flourish, and in 1939 we see the premiere of To Periodiko Mas, a magazine published by Nikos Kastanakis. This Greek magazine was the first to include comics. Kastanakis, an inventive publisher, created the comics and mimicked diverse styles, giving the impression that different artists were working on the magazine. Unfortunately, after 25 issues, the magazine ceased its publication due to World War II. In 1945, after the war ended, a new magazine called To Ellinopoulo, hit the stands. On the last page of its 5th issue, the magazine started a new single page comic called Bibikos drawn by Kostas Papadopoulos. These early stories were mostly rip offs from comics published in the Italian kids magazine Corriere dei Piccoli. The stories, following the Italian text, were written in octosyllabic rhyme, which fit perfectly as narration method for kids and was adopted by many Greek kids magazines of the era. Bibikos stories began to have original material thanks to the great Greek painter Michael Papageorgiou (artistic name Doris). After Ellinopoulo ended its run, Papageorgiou continued to create stories with Bibikos for the new magazine Thisavros ton Pedion. The Bibikos character had an important place in the history of Greek comics, as he is the hero of the first comic book published by A. Samaras. Bibikos o Efevretis, published in 1950, included 16 single page strips and was the first issue of the comics series that possibly run for four issues (issues 2 – 4, if they truly do exist, are considered “lost”).

Pulps Come to the Rescue

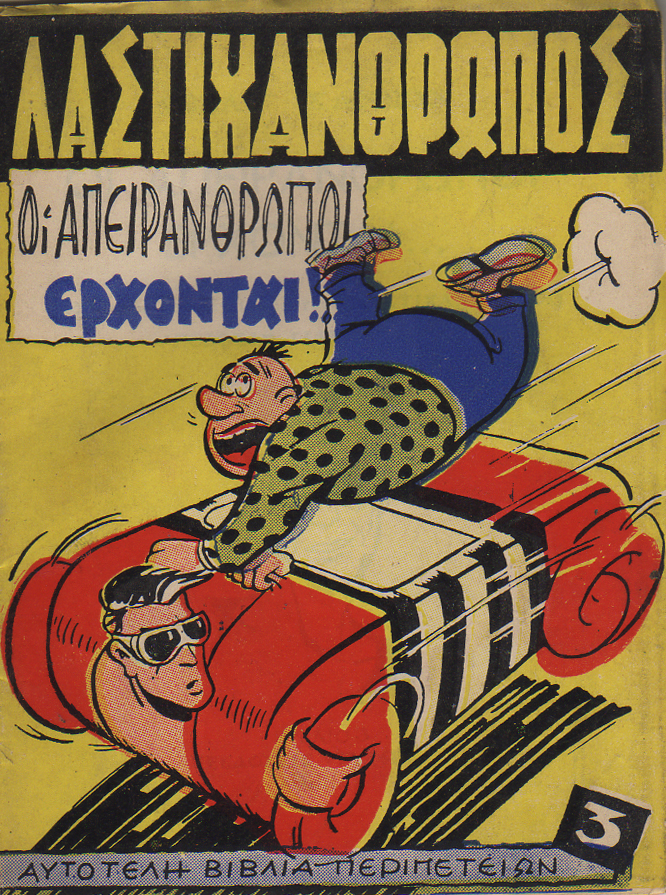

In the same year, Tam-Tam, another comic book was created – the first of its kind – that was exclusively dedicated to comics (though stories were given a more cinematographic style, with a picture per page highlighted by text). In this series, we saw a Greek version of Superman, here called Iptamenos Magos, who (curiously) retained the emblematic “S” on his chest. On the back page of this series, we also met for the first time Disney characters. This story was drawn by Viron Aptosoglou, one of the most important Greek artists of the period. Almost at the same time, in 1952, a new pulp series was created by Stelios Anemodouras (under the pen name Thanos Astritis) and illustrator Viron Aptosoglou (under the artistic name Byron), called Iperanthropos.

The heroes were heavily based on Captain Marvel and the Marvel Family with the addition of a comedy relief character called Kontostoupis, based on Archie friend Jughead. In a similar way to Iperanthropos, many of the Greek pulps were heavily “influenced” by the American publications of the era, using for prototypes characters such as Tarzan, Plastic Man, the Shadow, the Phantom etc.. Iperanthropos was one of the most successful Greek pulps of the time and had a run of 96 issues. So, in 1952, the publisher tried to create a special edition comic version of the series with Ikonografimenos Iperanthropos, created by the same team of the pulp series. The series lasted only 2 issues, but remained in history as the first Greek sci–fi / superhero comics. There is a clear connection between the Greek pulps and comics, as the writers and artists were the same. Still, it’s obvious that until the middle of the ‘60s, the less expensive pulps had the majority share of the market and attracted young readers.

The Classics Cometh

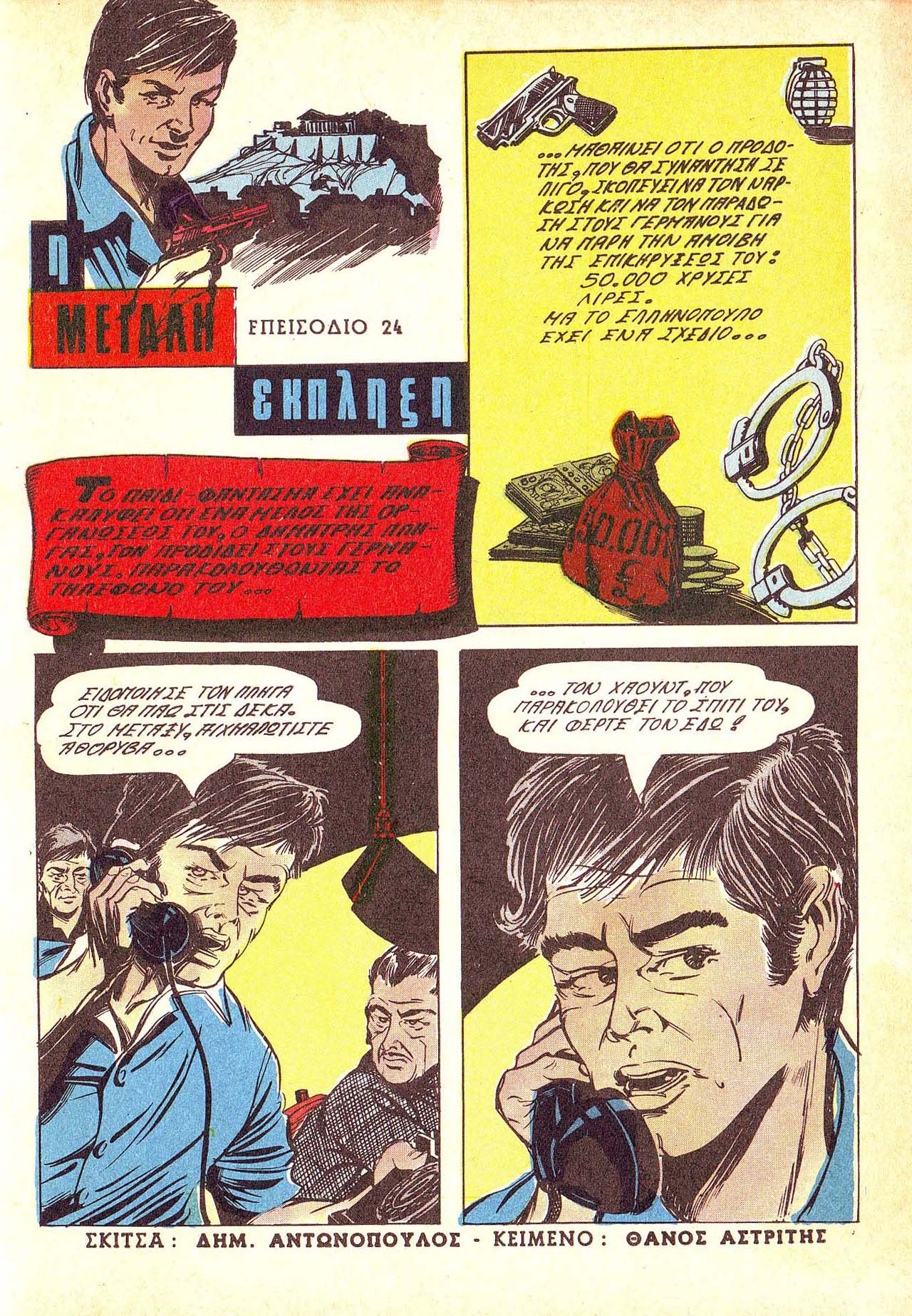

In 1951, publishing house Atlantis, founded by the Pechlivanides brothers, started Classics Illustrated in Greece. The success of the title was enormous and although the first issues were reprints of the U.S. edition, at a certain point, they began publishing all-new Greek material. These stories were based on ancient Greek mythology, stories from the Byzantine era, but also stories about the Greek revolution of 1821 and its heroes. Atlantis had a powerful artistic group at the time and many of the artists were – or evolved – into some of the greatest artists in the history of Greek art. To name a few: Giorgos Vakalo, Bost, Kostas Grammatopoulos, Nikos Kastanakis and Alkmini Grammatopoulou. In 1967, the most well known Greek pulp, Mikros Iros, in which a group of teenagers are fighting the Nazis in the occupied Greece during World War II, created by Anemodouras / Aptosoglou, (the same team that gave us Iperanthropos in the ‘50s) ceased its publication due to the Greek junta. To keep its hero going, the team started a new title, not in pulp form this time but exclusively as comics called Ikonografimenos Mikros Iros. In the series that ran 66 issues, Dimitris Antonopoulos replaced Aptosoglou on his artistic duties in issues 22 – 27.

The “Dry” Seventies

In 1970, a new Greek western comics called El Joe is published, written by Panos Pachnelis and illustrated by Giannis Koutsouris. This only lasted for 3 issues. The same as Timo, a humorous kids comic book, that was written, drawn and published by Nikos Kastrinakis. Comics by Greek creators were almost nonexistent in this decade, but that had nothing to do with the talent of the creators. The main reason for this phenomenon was that it was more convenient for a publisher to buy the (mostly) cheap rights for a foreign comics title, rather than create new original stuff which was rather costly and a potential business risk. The market was flourishing with Greek editions of comics from the United States, Italy and England. Il Grande Blek, Marvel Comics titles such as Spider-Man and Captain America, The Phantom, Tarzan and by the mid-70s, characters such as Judge Dredd or Johnny Red featured in the weekly comic anthology book Agori, were dominating the Greek newsstands. In 1978, Coloubra, a more adult oriented comics anthology book published by Vassilis Toufexis, hit the stands. In its pages, you could find comics from artists such as Robert Crumb and Guido Crepax – unknown at the time to Greek readers. Also, Greek creators such as Lazaros Zikos, Elias Politis, Miltos Skouras and Vasilis Dazeas were hosted in the comic book.

Childhood’s End

Although Coloubra lasted for only 15 issues, it was the spark that fired the ‘80s explosion of the Greek comics scene. On December 1980 a new anthology comic book called Mamouth Comix hit the stands, published by Mamouth Comix! It started by hosting works of famous artists such as Pratt, Manara, Garcia, Cavazzano and continued with also Greek works. Mamouth Comix continues till these days its activity publishing with a great variety of titles, mainly French-Belgian, such as Lucky Luke, TinTin, Asterix and Thorgal. In 1981, things began to change with a new comic book called Vavel. Creators such as Pratt, Bilal, Manara and many Greek artists showed their work for the first time to Greek readers. Some of the Greek artists were Petros Zervos, Elias Tabakeas, Giorgos Botsos, Arkas and the great Yannis Kalaitzis with his famous comics Tsiganiki Orxistra. This story was never completed in the pages of Vavel, but in 1984, Politipo editions published the complete album. Kalaitzis’ fresh line, along with his beautiful b&w sketches and storytelling, made this album one of the best comics of its era. In 1985, an editorial team controversy resulted in a split that led to the creation of a similar comic book, called Para Pente. Para Pente continued to publish Arkas stories, along with newcomers such as Spiros Derveniotis and Spiros Verikios.

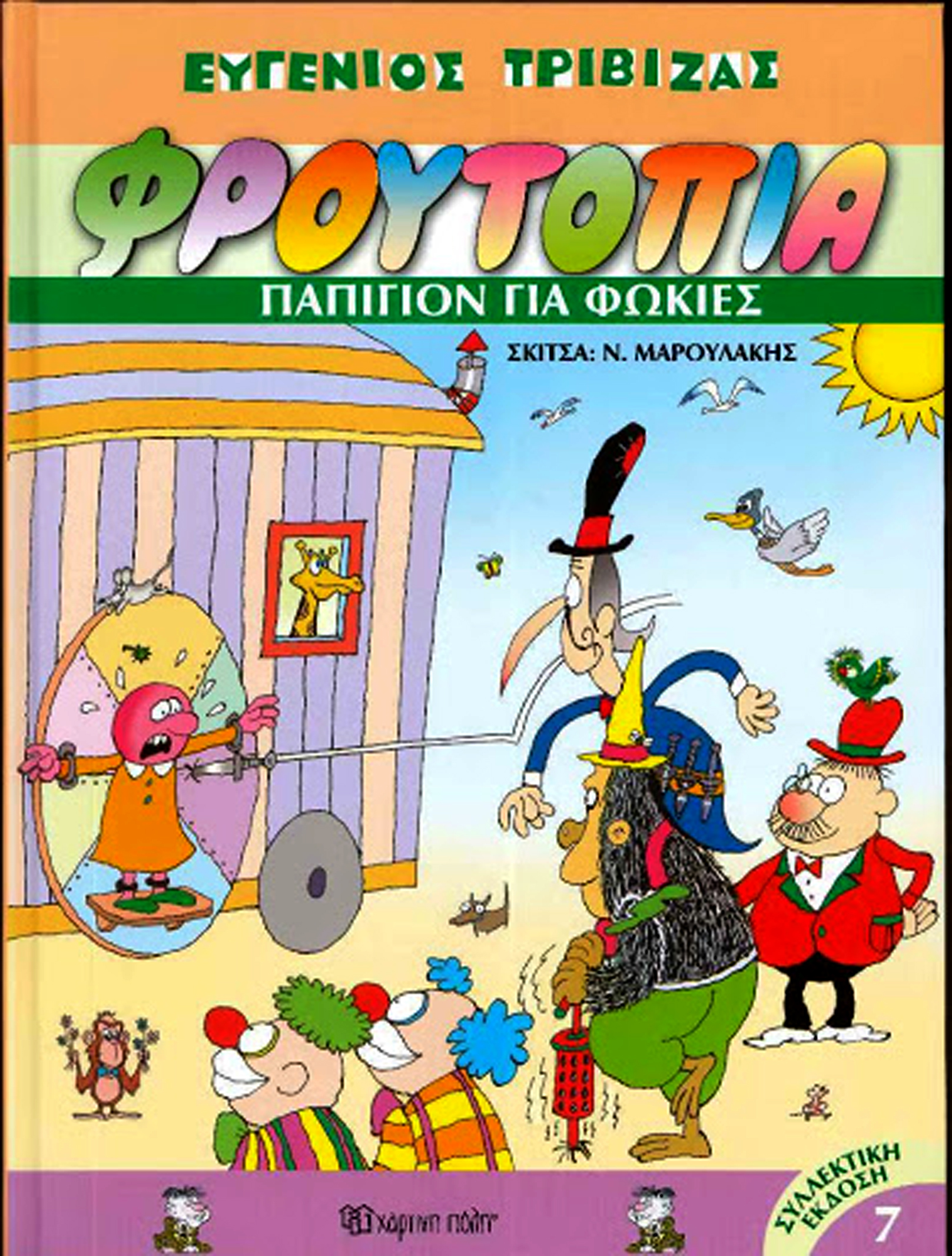

The following year, Frutopia, a new children comic series by Patakis editions, is published, written by the famous author Eugenios Trivizas and illustrated by Nikos Maroulakis. It was a very successful series that ran for 50 issues and also became a hit TV series, which remains a classic still to these days. In the ‘80s, many new creators published their stories and many new publishers entered the comics scene. One of the most important was Agrotikes Sineteristikes, that ran a very successful series with the comic adaptation of the Aristophanes comedies. They were written by Tasos Apostolides and drawn by Giorgos Akokalidis. These stories have been reprinted many times and remain successful until these days. In 1989, another important comics artist, Soloup, made his debut with Anthropolikos. But though things looked more promising than ever, sales stated to decline in the ‘90s. In 1995, Para Pente ceased its publication. Factors such as change of life style, private TV and technology development led to the decline of the comic book sales and made it harder for Greek artists to publish their work.

The Dawn of a New Era

Entering the 21st century, in June of 2000, a game changer makes its debut. Its name is a simple number, 9, which symbolises the 9th art, as comic art is called. This anthology comic book, published weekly and given with the newspaper Eleftherotypia brought comics back in the scene for both readers and creators. Highlights of 9 were Manifesto by Ilias Kiriazis, Xomateri by Leandros, one of the best comics creators of his generation and Mana Raver by Spiros Derveniotis. Many new creators entered the scene: Yiannis Rouboulias, Tasmar, Tomek. Self publishing and fanzines also had their share in this glorious decade for Greek comics.

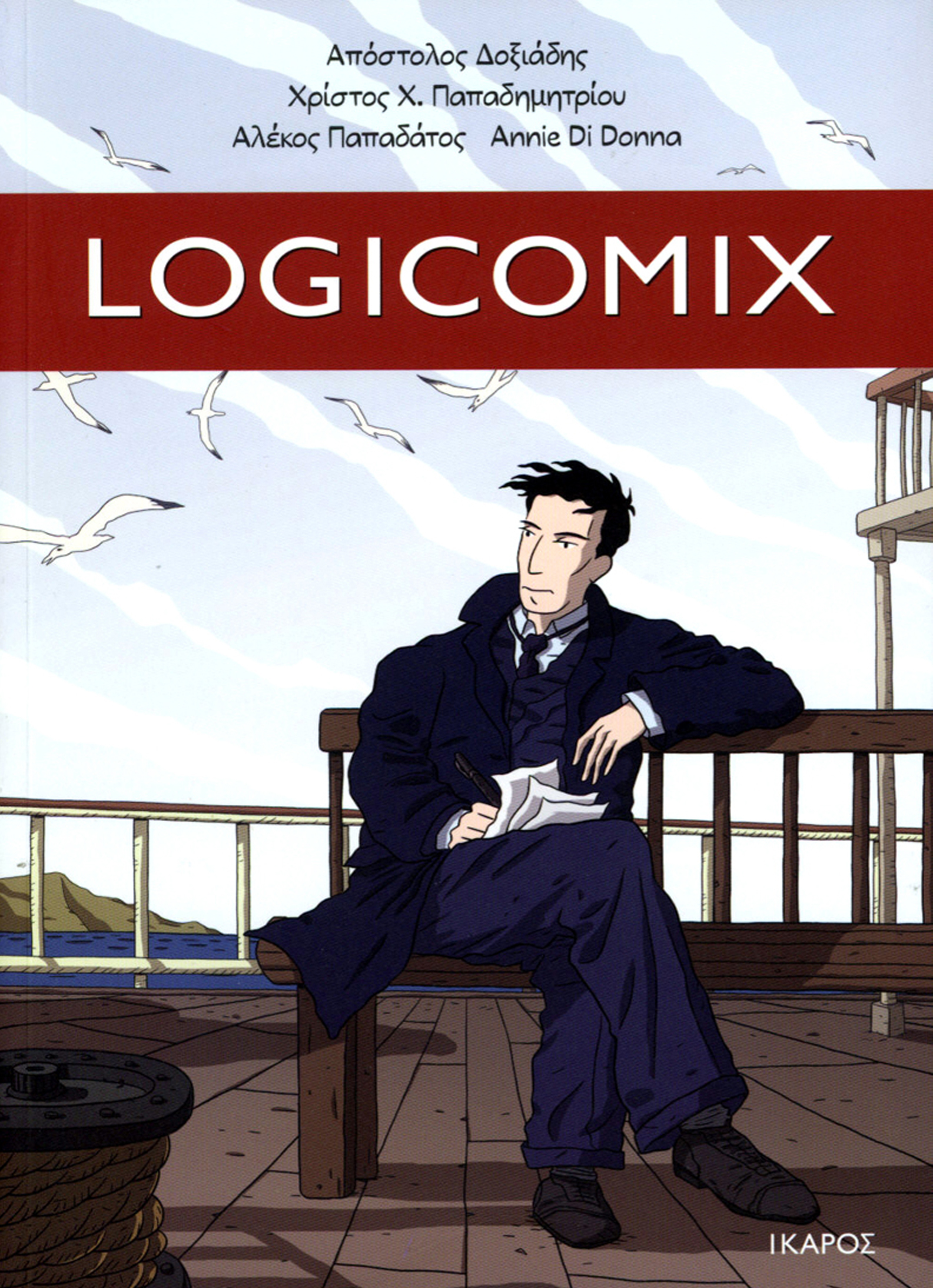

However, the most successful graphic novel of that period was Logicomix, published in 2008, by Apostolos Doxiadis, Christos Papadimitriou (writers) and Alekos Papadatos (artist). Logicomix was an instant bestseller not only in Greece, but also in the United States, Holland and Great Britain. Although it was originally written in English, its creators decided for it to be published first in Greece. In 2008, Vavel ceased publication and that was the end of an era for the most important Greek anthology comic book. In 2009, the publisher tried to relaunch the magazine under a new name, MOV, but this new project lasted only 9 issues. One year after the end of MOV and exactly 10 years after, 9 also ceased its publication.

Re-inventing Greek Comics for the 21st Century

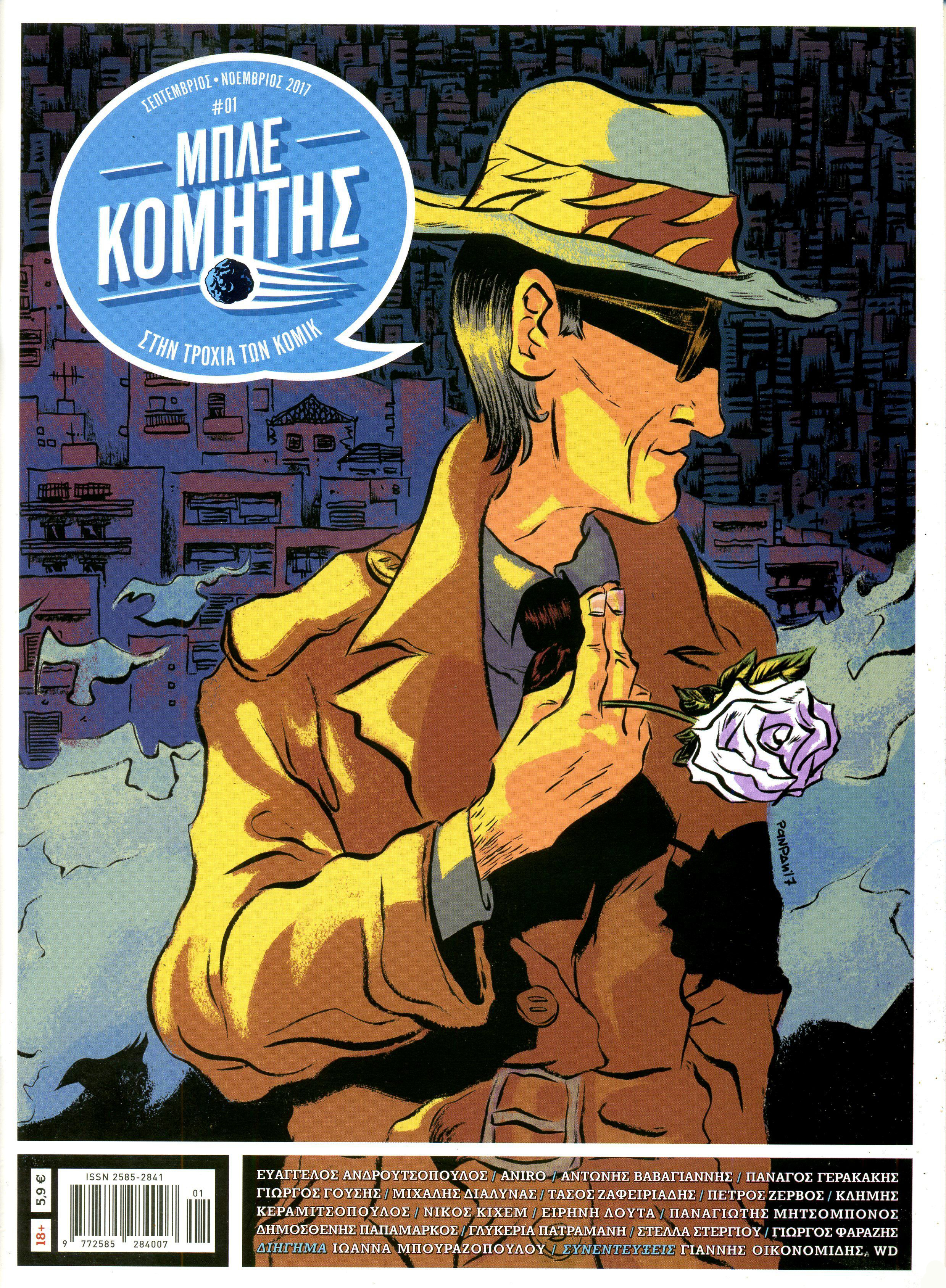

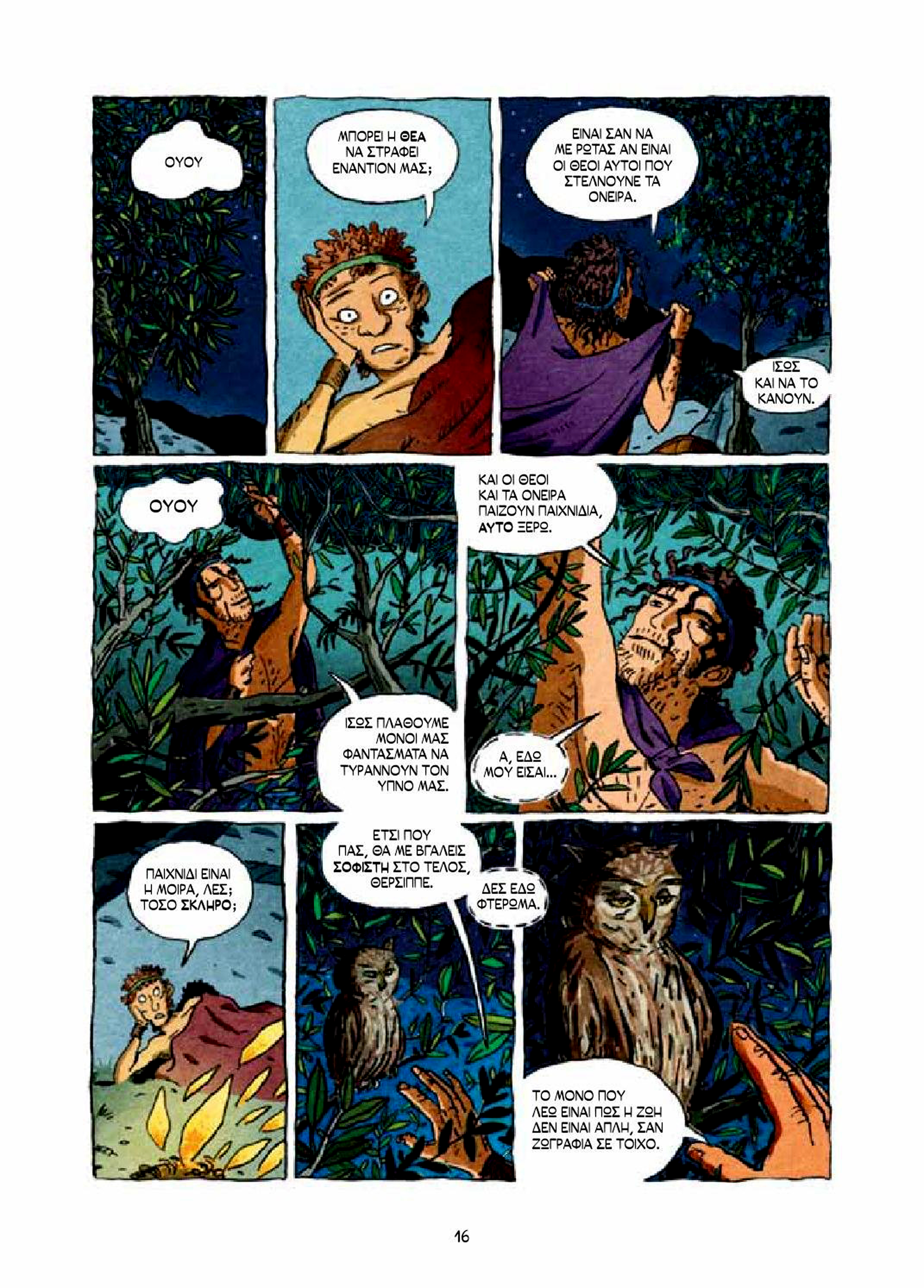

Obviously, the closing years of the ‘10s show worrying signs for the comics scene’s future. But, despite the economic crisis, the comics continued to grow. Greek artists such as Michalis Dialinas, Ilias Kiriazis, Nikos Koutsis and DaNi started working abroad, collaborating with great publishers (Marvel, IDW and Image Comics). Seven years after 9 ceased its publication, another attempt for an anthology comic book was made (in November 2017), this time based mostly on Greek artist. Mple Komitis, published by Polaris, ran only 9 issues but in that short period presented stories from many new creators such as Stella Stergiou and Stavros Kioutsoukis, as well as already established ones such as Petros Zervos, Ilias Kiriazis and Michalis Dialinas. The editor of this comic book was Giorgos Gousis who is also a comics artist. He illustrated the graphic novel Erotokritos, written by Dimosthenis Papamarkos and based on Vincenzos Kornaros early 17th century romance novel.

Reinventing Greek literature through comics was an idea received well by the Greek comics audience and therefore we had many new similar editions. To name a few: Kerenia Koukla (Comicdom Press, 2017) by Elias Katirtzigianoglou and Christos Tsiamantas based on 1911’s Konstantinos Christomanos novel and Parlarama and Other Stories (Topos, 2011) by Dimitris Vanelis and Thanasis Petrou based on Dimosthenis Voutiras novels. Greek history was also a source of inspiration for graphic novel creators. In this field, we have Democracy (Ikaros, 2015) by Abraham Kawa and Alekos Papadatos, a story that takes place in the 5th century B.C. in the city of Athens; Aivali (Kedros, 2014) by Soloup, focusing on memories from the events surrounding Asia Minor Catastrophe and 1800 (Jemma Press, 2019) by Thanasis Karabalios, in a story that takes place two decades before the Greek Revolution of 1821. A new decade it’s just around the corner. Creating comics and making a living from it is still difficult for the vast majority of Greek creators. But despite all the problems, Greek Comics can look with optimism to the future, with the potential that a new era for the medium is coming.

Article written by Gabriel Tombalidis, MIKROS IROS PUBLICATIONS LP.

Header image: Detail from the cover of Erotokritos (2016). Art by Giorgos Gousis.