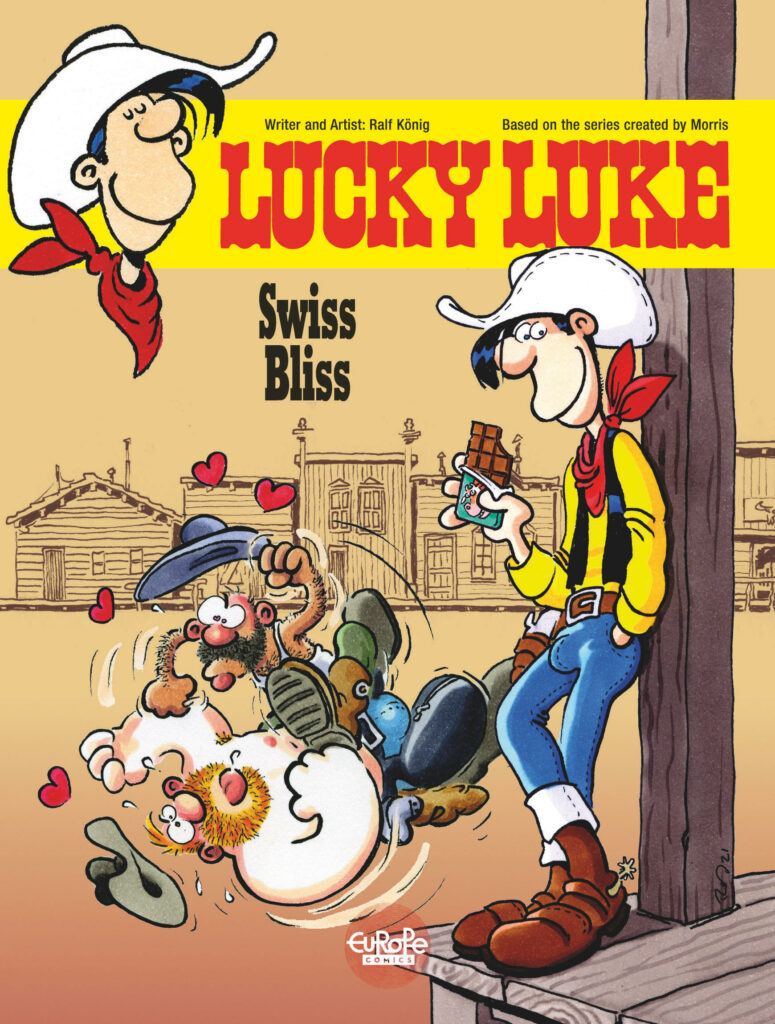

German author Ralf König, an artistic pioneer of homosexual emancipation through his humorous comics, sat down with the Italian online magazine Lo Spazio Blanco to talk about his new Lucky Luke. To celebrate the character’s 75th anniversary, Ralf König took a new offbeat look at the poor lonesome cowboy…

Lucky Luke is one of the best-known comics characters in Germany, competing with Asterix, Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. You, together with Mawil, are for now the only foreign author to have paid homage to the character, on the occasion of his 75th anniversary. How was the project born and what did it mean for you to write this story?

My boyfriend at the time worked at Ehapa, the Berlin publishing house that had the German illustrator Mawil draw Lucky Luke, and I must have sighed at the kitchen table that I’d like to do that sometime, but I didn’t trust myself with the whole Western setting, with carriages, horses, wooden furniture. Olaf then reported this to the publishing house and their ears immediately perked up. Then there was a meeting with the editor-in-chief and I had the job on my hands. I was happy about it, but also worried that I wouldn’t get it right. At first I had a rough idea for the plot, but later everything came differently and the originally planned rustlers became autograph hunters. I always work very spontaneously, I never do a script with the finished dialogue beforehand. It develops dramaturgically only when drawing, doing the text and image, and often leads me in completely different directions than initially thought. That carries the risk of getting carried away and drawing a lot for the wastebasket. But it keeps the creative fun for me. I would get very bored drawing if I only had to work off a kind of fixed script.

Did you read Lucky Luke as a child? Could you consider Morris as one of your inspirations?

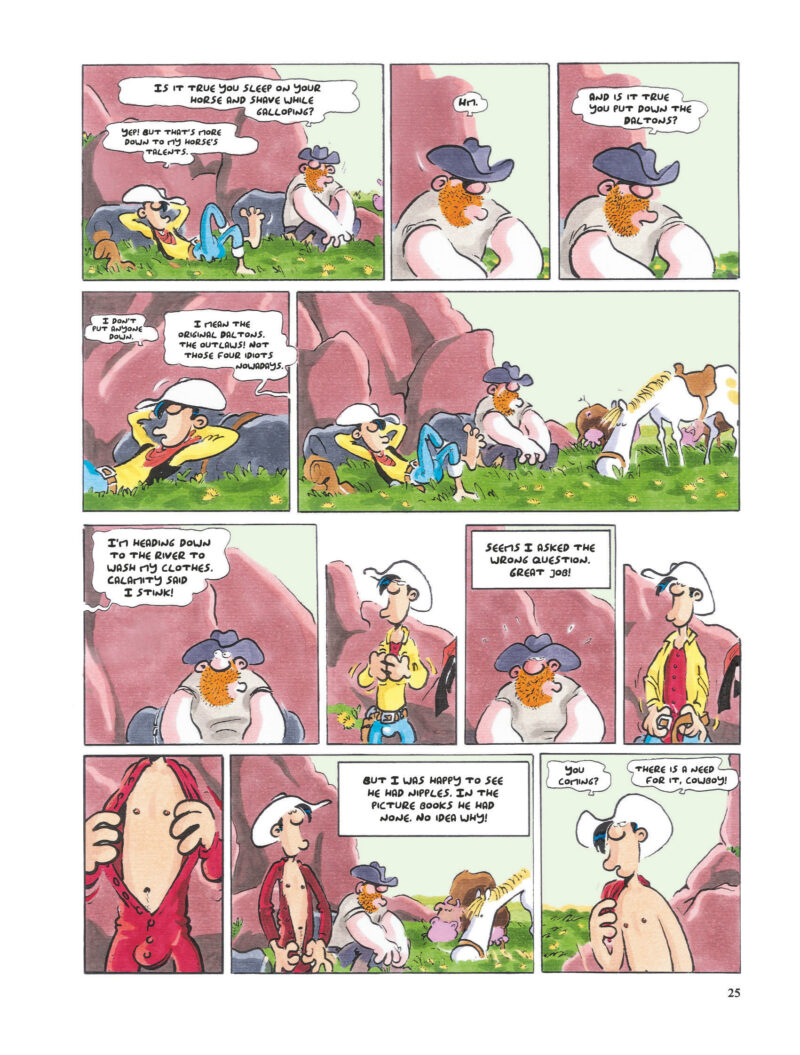

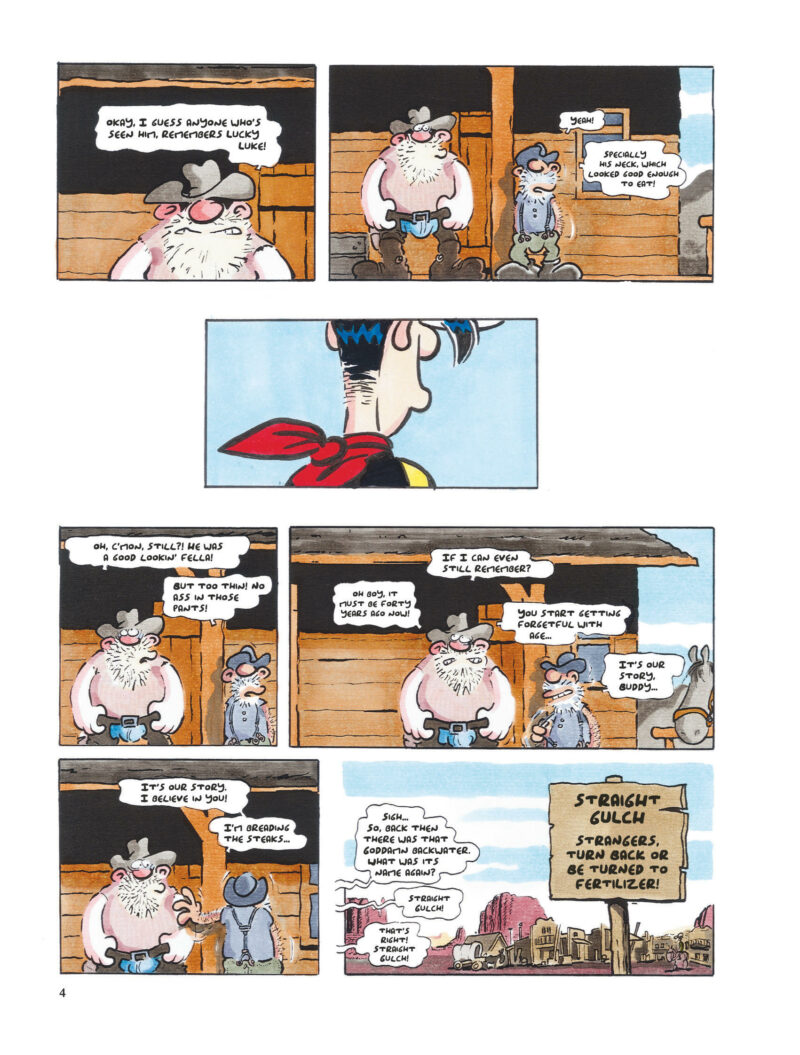

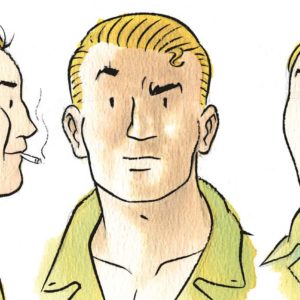

Yes, of course, I was a Lucky Luke fan as a child. One of the first comic books my mother gave me was Calamity Jane. I was fascinated by the comic because of this cursing gun-wielding lady. And as a kid I thought Lucky Luke was very sexy. Those fine black hairs on the back of his neck turned me on before I knew anything about sexuality. I used to draw on his nipples, which were missing for some reason, with colored pencils when he sat in the river or in the bathtub. And, of course, I didn’t yet understand how ingenious Morris was when it came to drawing lines. When you’re a kid, you just accept it. It wasn’t until later that I admired this scribbled ink stroke, the spontaneity that still remains in the drawings. Unlike with Asterix, everything was always perfect. And now, while drawing the book, I realized what incredible drawings the man had made, the perspectives. A whole western town from a 45° bird’s-eye view. The legs of the horses. The exact posture of the figures. I was really frustrated the first week that I would never be able to do it, but then my friend reminded me that it was supposed to be ‘my’ Lucky Luke and that I shouldn’t be imitating Morris. And when I understood that, it worked out well. It took me 6 months to make the book and the whole process was a joy. Everything worked out, even with the page numbers the story came out perfectly. And I didn’t know until page 41 that the Daltons were going to be on page 43. Great fun!

Your story fully captures the spirit of the character: what were the stories that most influenced this characterization?

It was clear that Calamity Jane would be in the story. I also found the Daltons overused by Morris, in every other volume there were the Daltons, but it was great fun to draw them when I needed bandits for the story. Because the autograph hunters weren’t evil enough. But I also watched a lot of westerns, on Netflix and DVD. I didn’t know all the Italo-westerns, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and so on. I like to put myself in the right mood with movies and music.

Despite being a Lucky Luke story, the real main characters are Terrence and Bud, the two homosexual cowboys who are also the narrators of the story. Reading them I could find a bit of Konrad and Paul, the characters you created and that continue to be part of your story and career: am I wrong to say that this Lucky Luke is also a bit of a continuation of your series and your poetics, where you use irony to talk about important and delicate issues?

Well, in principle, it is, yes. I’m gay and I’ve been drawing comics that come from my gay life for 40 years, but I don’t see myself as an activist or an educator, even though that has certainly happened. That also makes me pleased, I like being a cog in the gay wheel. But what’s important to me are cool comics, not educational reading. I am a gay comic artist and I like to draw about love and sex. So my Lucky Luke has only a limited connection with Konrad and Paul. Sure, little Terrence reminds me of Paul, because he is small and hairy, but that was not my intention. Big and small is popular in comics, the Asterix and Obelix principle.

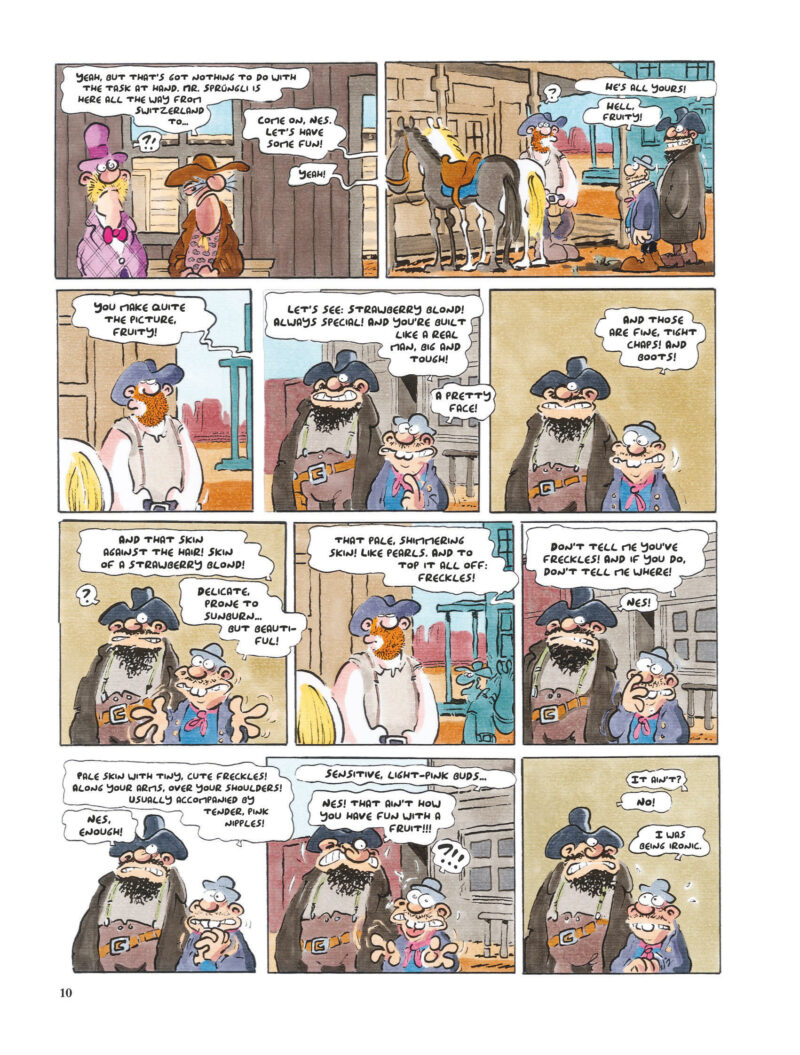

Homosexuality hasn’t typically been linked to the Western genre, despite what you yourself say at the end of the volume (that is, even in the far west homosexuality existed). I particularly liked the contrast between the attitude of Lucky Luke, who is immediately involved in the story of the two cowboys in love and actively wants to bring them back together, and that of the rest of the community, which constantly teases them with the nickname Steckruebe (literally “rutabaga”). This creates constant games and short circuits that make the villagers appear to be total idiots. Do you think that irony is the strongest weapon against homophobia and discrimination?

Yes, irony and humor are a strong weapon. If not, religious and other idiots wouldn’t be so afraid of cartoons. From that point of view, with Lucky Luke I’ve drawn a comic that should enlighten a bit, because it will probably find many readers who don’t know about my other books. For example, I’ve never drawn a coming-out story before, but here we finally have one. Sure, subliminally it’s about fear and violence, but it transports much better through humor.

Another character that was particularly entertaining is the autograph hunter, which fits into a larger metanarrative context that you use to break through the fourth wall and create an extra layer of humor. Does that kind of nerdy world, sometimes a bit fanatic, more amuse you or perplex you?

Both. I get these autograph requests through publishers in the mail and often I have the impression that these people know nothing about who I am, but want at least three autographs to exchange. And the letters are often written very obsequiously, saying that they have been big fans for years and asking if I could be kind and fulfill their very big request and sign photos and also a drawing on cardboard or even portraits of their own noses. A little spooky. I often don’t do that. But if someone really knows and loves my books, I’m happy to do it.

Have you ever met one of these autograph hunters in your experience?

I see these people at every comic festival, back when comic festivals still existed, and they push their rolling suitcases from one artist to the next. But they’re often very demanding, almost impertinent. As if it were the artist’s duty to fulfill their wishes.

One more element of great fun in your comic is the huge number of quotes and references, from the names of the two cowboys (Terence Hill and Bud Spencer are two idols in Germany) to the name of the high ground of the pasture (Bareback Mountain, a clear reference to Brokeback Mountain, the movie by Ang Lee). Are you a fan of the genre or did you have to do particular research to build this type of puns and word games?

No, not a fan, and I always found the Bud Spencer and Terence Hill movies too foolish. Brokeback Mountain moved and inspired me, of course, even more the literary short story than the film. There are no gay references in westerns except for the funny scene in the classic Red River where the two cowboys compare pistols. But I always found Lucky Luke sexy, as I said. When I was a teenager, I discovered these porn parodies from Holland, where Lucky Luke has sex with girls all the time. It was not badly drawn and triggered the erotic factor of the cowboy even more. Such word games are in all my books. I’m good at language, whether it’s Shakespeare, the Bible, or antiquity and the Middle Ages. I read about it and it flows into my dialogues. That comes easily to me.

Your style is always very recognizable. How do you work? I understand that you work only on paper, without the use of digital…

Yes, I do not like technology in drawing. As long as there is paper and colored pencils, I will provide hand-drawn work and not computer files. Besides, I like to have the originals afterwards. The only technical tool is my light table for tracing contours. Otherwise, pencil, scissors, glue, ink pens, colored pencils, everything old-fashioned analog.

In your career you have made both black and white strips and color stories. Does anything change for you when you use colors? And what additional level of expression do they allow you to give to your drawing?

In color, of course, it takes longer, because I have to make decisions for each sock and curtain. But I decide depending on the story, whether to do it in color or not. I find black and white or just shades of gray just as appealing. But if, for example, there are a lot of animals in the story, like in Archetype, my bible-flood story, then it should also be nice and colorful.

In 2020 you marked 40 years of your artistic career, even if, due to the pandemic, you were only able to celebrate that in 2021 with a Comiclesung (public reading of comics). On your website you confess that the first issue of Schwulcomix was produced for fun, looking at authors like Robert Crumb, but that you would not have thought you would still have been, 40 years later, a comics author (and the most famous German author abroad). Looking back on these years, what evaluation can you make of your career?

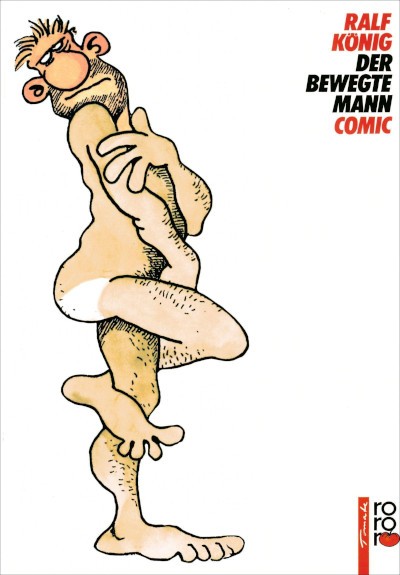

I was enormously lucky to hit a taboo with my gay comics. We’re talking about the early ‘80s, when homosexuality in Germany was still something dingy, out of touch with society. There was no education. And then came someone who made funny stories about it, which had something liberating for a lot of people, even though that wasn’t what I was aiming for. I just wanted to draw cool comics, like crumb’s Fritz the Cat or later Claire Bretécher with Les Frustrés, which I adored. So I came up with humor at just the right time. The first big book success was Der bewegte Mann (Maybe… Maybe Not) in 1987, the first time I published with a non-gay publisher, which was also an advantage. This was followed by a very successful movie in Germany based on my comic, which was in 1994. I was very lucky and inspired by role models and always had this passion for drawing comics. But I don’t know where that comes from. I’m the only artist in my whole family. My family is not interested in what I do, but they are happy about the success.

During your career you have been publishing mostly with Rowohlt, which has published and supported you since 1987. How important was it for you to have only one publisher who you can trust and work with? How did you start to work with this publisher?

I had studied free graphics at the art academy in Düsseldorf, alongside Joseph Beuys, and when my studies came to an end and I didn’t want to go back to a carpenter’s shop, because I had previously been a carpenter, I applied to various major publishers and Rowohlt was the only one to respond positively. Also a stroke of luck. Since then I have always worked for at least two publishers, Rowohlt as a big publisher and Männerschwarm as a small gay publisher, for more internal gay comics with maybe a little more sex. But that doesn’t matter, Rowohlt also publishes my dicks today. The main thing is that when the dicks are a little smaller than the noses, then it’s not porn.

What, in your opinion, has changed in the world of German comics? In recent years, many authors who care about issues often addressed in your comics have emerged and developed their own voices.

I don’t know about that at all. I read none of these comics and don’t follow what’s happening in the German scene. Really? Do authors deal with my topics? I generally have the impression that comics come across as very staid in these times of political correctness. And too sophisticated. I’m not interested in a biography about Otto von Bismarck or anything like that. For me, comics are still a bit of rock ‘n’ roll.

With your stories full of irony you have anticipated important issues, not only regarding the LGBT+ community, but also issues such as gender violence, violence against women and so on. With respect to these issues, how do you think comics can influence society?

I am not very optimistic, I fear art in general does not change the world significantly. It will always be read only by those who want to read it and are open-minded and tolerant anyway. There will always be idiots and hate. But for those who see the world the way I do, hopefully it will still be fun to read my stuff and it will be worth it. I’m 61 now, so let’s see how long I keep drawing cool and relevant stories. The LGBTQ scene is more diverse than it was back then, which is a good thing, but only interests me to a limited extent. I’m sure for the young I’m the white old cis man, with outdated intentions about gender and sex, but that’s okay, that’s what I am.

More generally, did you see a change towards these themes and issues during recent years in German culture and society?

Yes, the sensitivity level is high, you have to keep an eye on the jokes, otherwise someone is quickly offended or knows someone who could be offended. But I don’t pay attention to that. I don’t even think of racist or trans-hostile dialogues and if a joke goes wrong, I’m capable of learning. I just insist on my often somewhat crude humor and I hate the new prudishness that comes with Facebook and Apple. I’m happy to be the dirty old man.

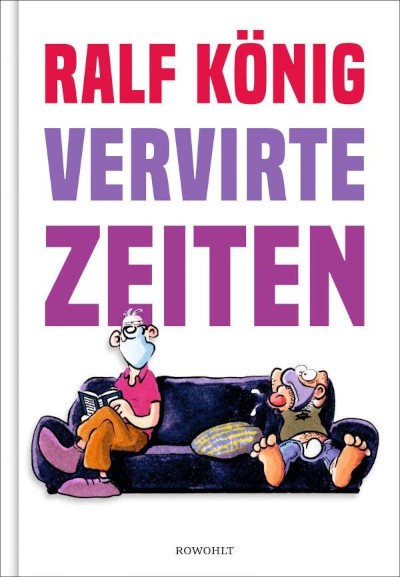

Coming to your latest works, during the pandemic, in addition to Lucky Luke, you worked on new stories of Konrad and Paul that appeared on your social media profiles. It was a tragicomic commentary of the first year of the pandemic, very different from all the others, which you collected in the volume Vervirte Zeiten (“Confused Times”). What did this book represent for you? And now that the pandemic is entering a new phase, how do you see audiences responding to your new stories?

These daily comics got me through the first lockdown, it was and is great fun to publish them and to get the direct reactions in the comment bars. I didn’t make any money, but the advertising effect was considerable and the later book with the collected strips sold very well. I had to interrupt the series because of Lucky Luke, but now I’m back to it daily and it’s fun again. But the difference is, now it’s winter and unfortunately I tend to get winter melancholy. That is, in the spring and summer I was better with the ink pen. Paul is getting on my nerves a bit with his horniness, but these figures now do what they want and I almost just watch. That’s how I function on autopilot.

Interview originally published in Italian in March 2022 by Lo Spazio Bianco. Interview by Emilio Cirri and David Padovani, in collaboration with Europe Comics.

Header image: Lucky Luke: Swiss Bliss © Ralf König / Dargaud