“Be Spontaneous!”

“Be Spontaneous!”

That’s the irritated command from the psychoanalyst to his glum patient subjected to a barrage of word associations. As if anyone can be “Be Spontaneous” on command. It’s a telling choice of panel for the cover of Psychanalyse (Le Lézard, Paris, 1990), a modest early booklet by Lewis Trondheim, because he has managed against all odds to remain defiantly spontaneous, while developing into one of the most prolific and acclaimed members of France’s ‘nouvelle vague’ of bande dessinée, and one of her most appealing recent exports in translations from Fantagraphics and NBM.

For all this success, his beginnings were not auspicious. For Psychanalyse (no relation to Psychoanalysis, Jack Kamen’s tissue-clutching 1955 EC comic book), Lewis’ artwork could not have been less spontaneous. He scribbled just six slightly different panels, three of them speaking, three silent, of the same simple cartoon head of his patient, reduced to a mouth, eyes, one ear and hair, and then he laboriously, maniacally, pasted together photocopied blow-ups of them in different sequences, 272 times over 14 pages. The very blobbiness of the enlarged lines and Lichtenstein-like screen dots in the background deliberately accentuate the mechanics of the artwork. There have been minimalist comics before, using the most basic of faces, figures and settings, but how minimalist can you get? (Actually, like a mad scientist, Trondheim has been trying to find out, by paring it down to only one repeated image and reportedly even experimenting on comics with no drawings at all). His visuals don’t reveal the escalating battle of wills being fought in his word balloons between the contrary patient, subjected to word association and Rorschach inkblot tests, and his unseen, ‘off-camera’ psychoanalyst. He ping-pongs their dialogue back and forth, inserting silent panels for comedy tension. Only when we get to the very last two panels does he finally break away from his patient’s limited repertoire of expression, first in a wordless panel of anxiety and then a last desperate shout for ‘Mama!’.

Trondheim’s initial ‘anti-drawing’, his pride in his apparent deficiencies, flouted the French-language commercial tradition of bande dessinée albums, the massive BD mainstream of Tintin and Asterix, Moebius and Bilal. This is founded on the full colour album, usually hardback like a children’s book or an art book, and usually starring action and/or comedy heroes in 46-page stories in series of as many as 30 or 40 books. Their quality paper, printing and generous page size are designed to capture the finest finished draughtsmanship, the work of maybe a year or more, in which spontaneity can be drowned by virtuosity and convention. At the outset, Trondheim could not, or would not, follow this model. His fellow cartoonist and co-founder of the independent publishing collective L’Association, Jean-Christophe Menu, summed him up in his preface to Psychanalyse:

“Because he has rejected anything like a BD stylistic effect, and stripped his language of every seductive and complacent flourish, Lewis Trondheim has managed to get to the very essence of the comics medium and on this evidence he has rediscovered a secret. Because he has achieved this tour de force by starting from nothing, now anything is possible in the false comics of Lewis Trondheim, comics that are the truest there are.”

I first met Lewis Trondheim sat behind his booth at a local bande dessinée fair outside Paris in 1989. He struck me as an intense, internal, determined chap, almost, dare I say, English in his reserve and eccentricity. Hot off the photocopiers were the first issues of his self-published Approximate Continuum Comics Institute H3319. I learnt he was a late starter, drifting into creating his own comics only the year before, when he was already in his mid-twenties, positively middle-aged in fanzine terms. He was born Laurent Chabosy in 1964 in a comfortable Catholic family, coddled in the Parisian suburb of Fontainebleau. The French rock magazine Les Inrockuptiples in 1996 described his secret origin biologically: “As a child, LT was hugely bored. As an adolescent, he vegetated. Now as an adult, he is like a maniac, pumping out all sorts of subtly strange albums… Rarely has such a larval childhood brought forth so brilliant, indefatigable and inventive a butterfly.” Reborn, he dreamt up his pen-name Lewis Trondheim. The ‘Lewis’ could have been a tribute to Lewis Carroll, bearing in mind his fondness for rabbits and strange metamorphoses. As for ‘Trondheim’, that’s a city and fjord in Norway, reportedly the coldest country Lewis had ever visited.

Trondheim is also the birthplace of Hal Foster’s medieval hero Prince Valiant and is also used at least twice in classic Monty Python sketches, for example as the hometown of the Vikings in the Spam sketch and the setting on one record album track for a traditional folk dance where the inhabitants hit each other regularly sticks. In the end, though, he has assured me that he chose the name mainly to avoid sounding at all French and to be tricky for French people to pronounce. In other words, to be deliberately awkward.

So what woke Lewis out of his shell and got him started? He was asked to contribute to Jeux d’Influences (Editions PLG, Paris, 2001), a book in which thirty bande dessinée creators wrote about which key works had inspired them to take up comics, and which had inspired them to continue. Trondheim responded, characteristically in his own non-conformist way, with a modest one-page, fixed-shot strip. He draws himself back in 1987, opening and reading his first copy of the experimental comics collection Les Lynx a Tifs. Bemused by the bizarre art styles, he decides to read it anyway, after all “I’ve paid for it”, and plumps for “one of the worst” by Matt Kontture. The last of the next three silent panels of him reading marks Trondheim’s deadpan, blank-eyed epiphany. It comes to him as a quiet, intellectual revelation: “Right… that’s drawn really badly but it’s interesting to read.” “That’s strange.” “Well, in that case, even I could make comics if I wanted to.” “OK, yes… all I have to do is try.”

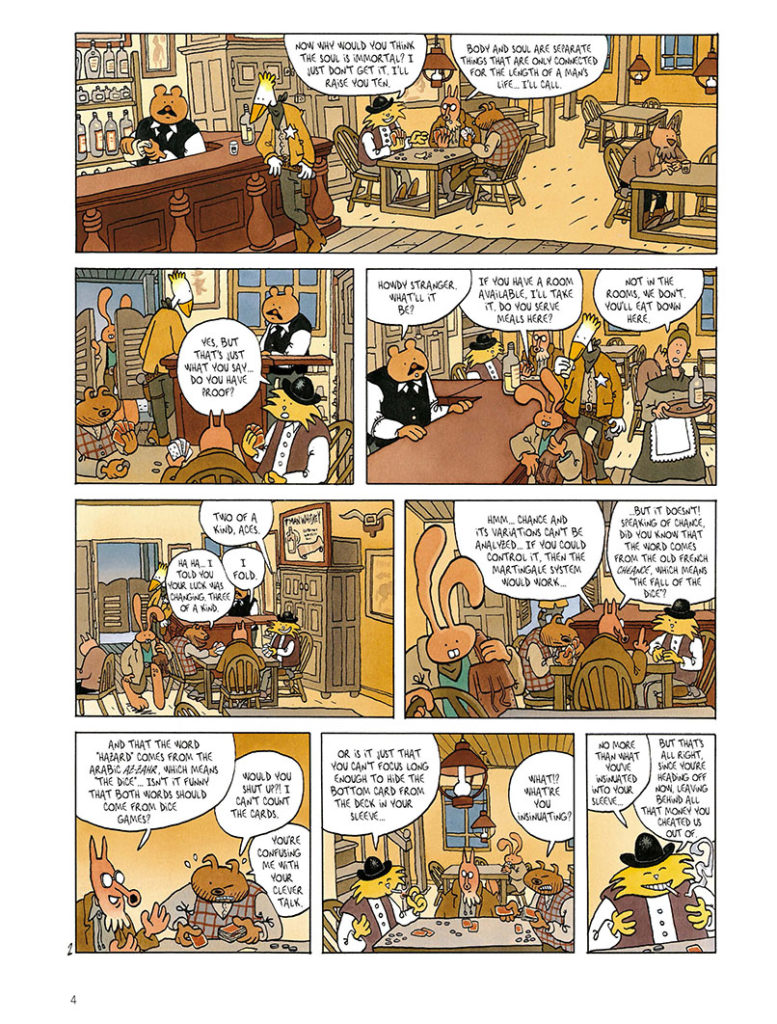

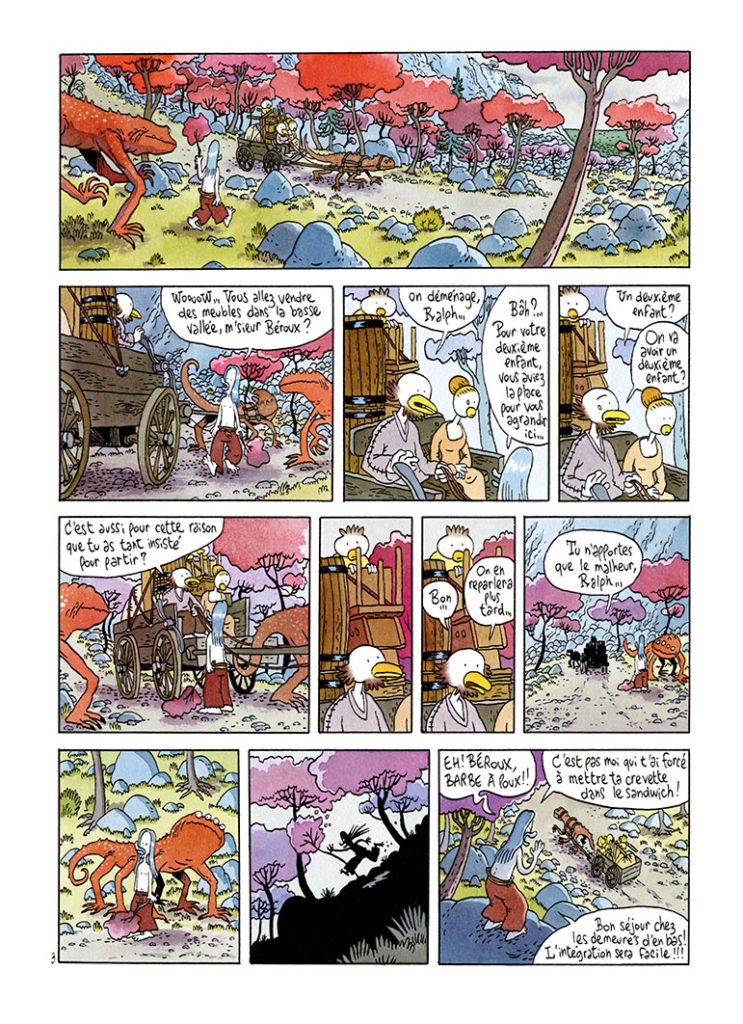

And try he did. You might think he would have settled for being strictly a writer, only sketching layouts for his scripts for others to illustrate, as for example the late Archie Goodwin used to do. Instead, Lewis taught himself to draw in public, undertaking a mad, mammoth self-challenge, to improvise a black and white, 500-page, 6,000-panel story, Lapinot et les carottes de Patagonie (L’Association/Le Lézard, Paris, 1992), making it up as he went along, much as Moebius had done serializing The Airtight Garage in the early Metal Hurlant magazines from 1975. Page by page you can watch Trondheim’s fresh, direct, economical cartoon style emerging and his confidence and sheer pleasure in discovering he can tell whatever story he wants growing before your very eyes. He started detailing buildings, interiors and street scenes in a loose clear line like a wobbly Hergé, while the facial expressions and body language of his Candide-like leading rabbit Lapinot and company acquired much of the vitality of Charles Schulz or Carl Barks. Trondheim has never re-read all this epic since and it doesn’t entirely stand up, except as an inspiring lesson in comics self-education and as a blueprint for things to come. Like Barks in his timeless Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge fables, one of Trondheim’s childhood passions, he too uses ‘unrealistic’ funny animals, rather than human beings, but makes us empathize with them for their all-too human foibles and contradictions. Lapinot might seem very rabbit-like with expressive, mobile ears and a penchant for carrots and hopping in his big bare feet, but otherwise he is a good-hearted, Tintin-like young man, the conflict and comedy usually springing from his less than reliable crony Richie the cat and his foil Doug the dog.

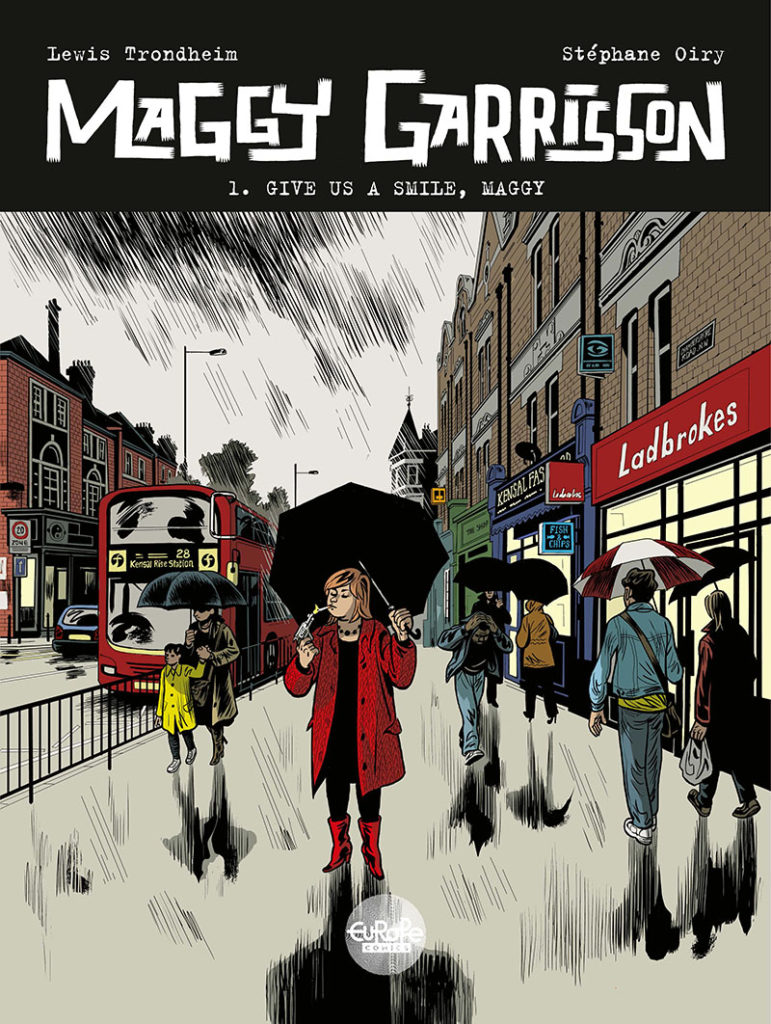

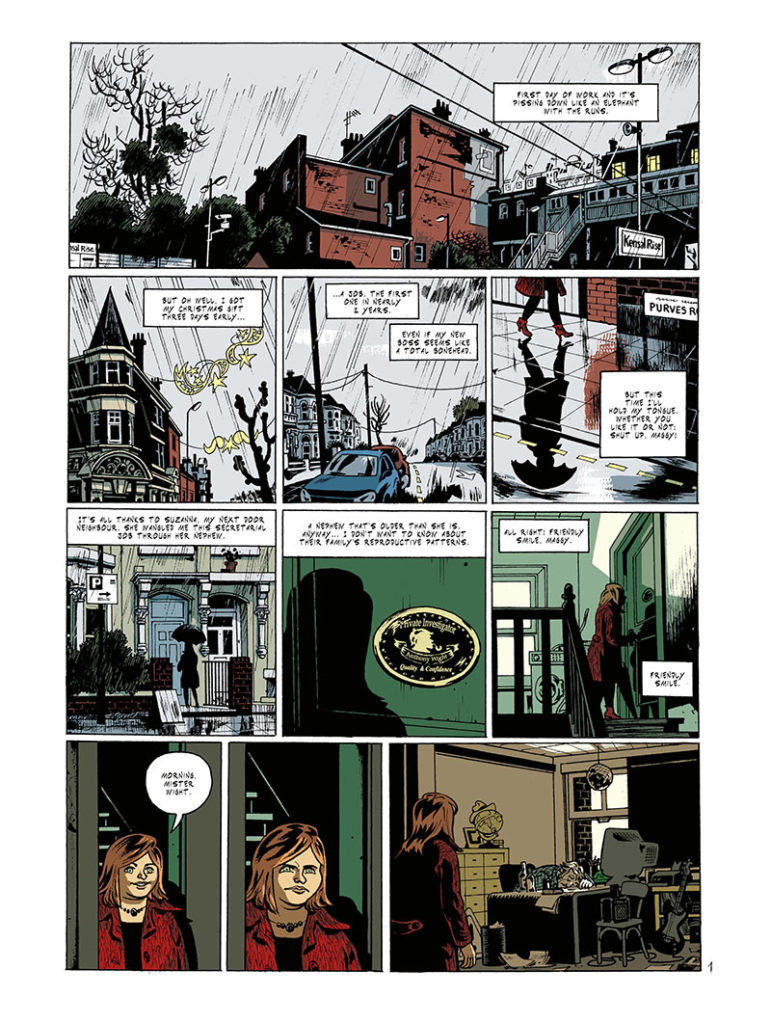

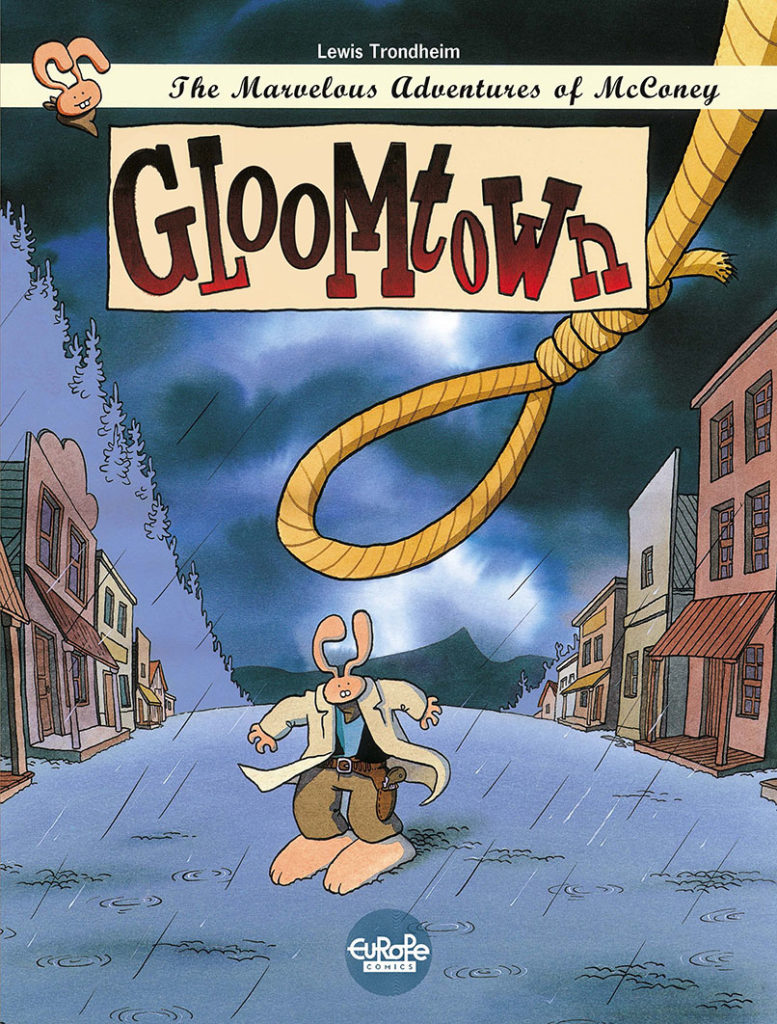

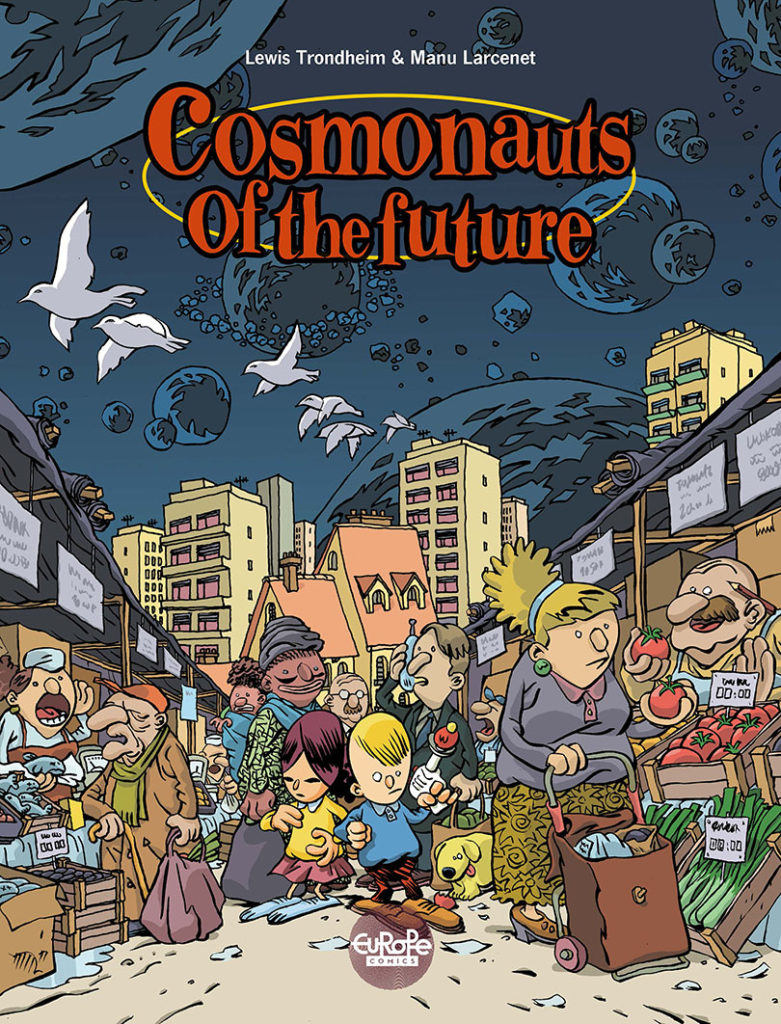

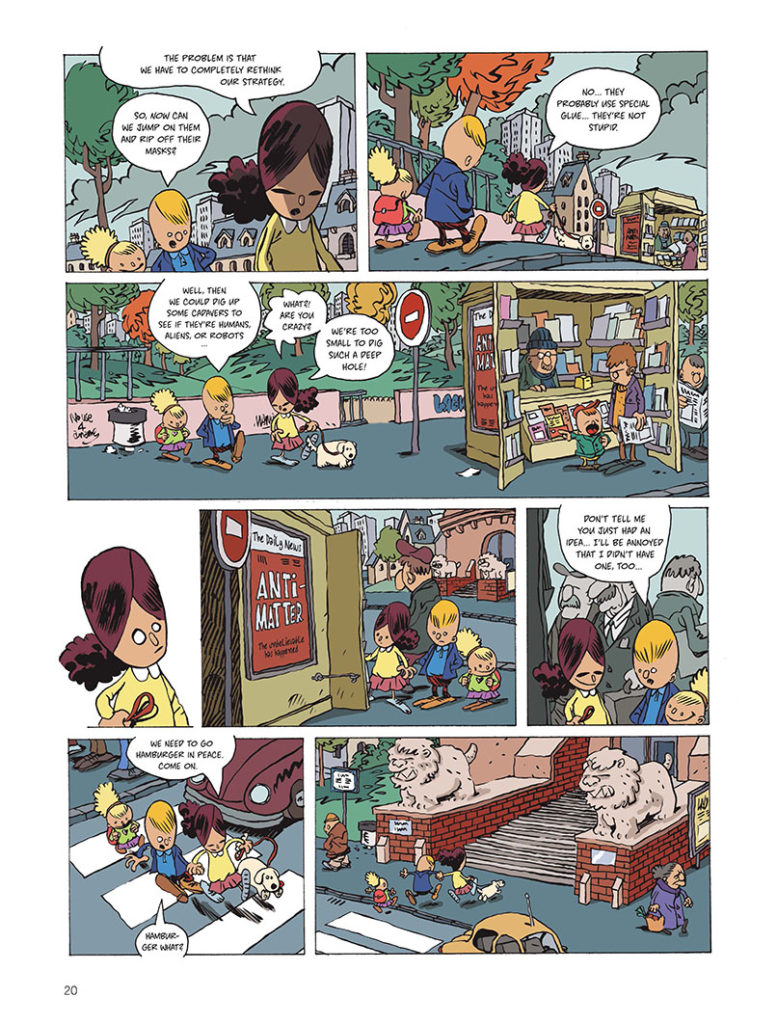

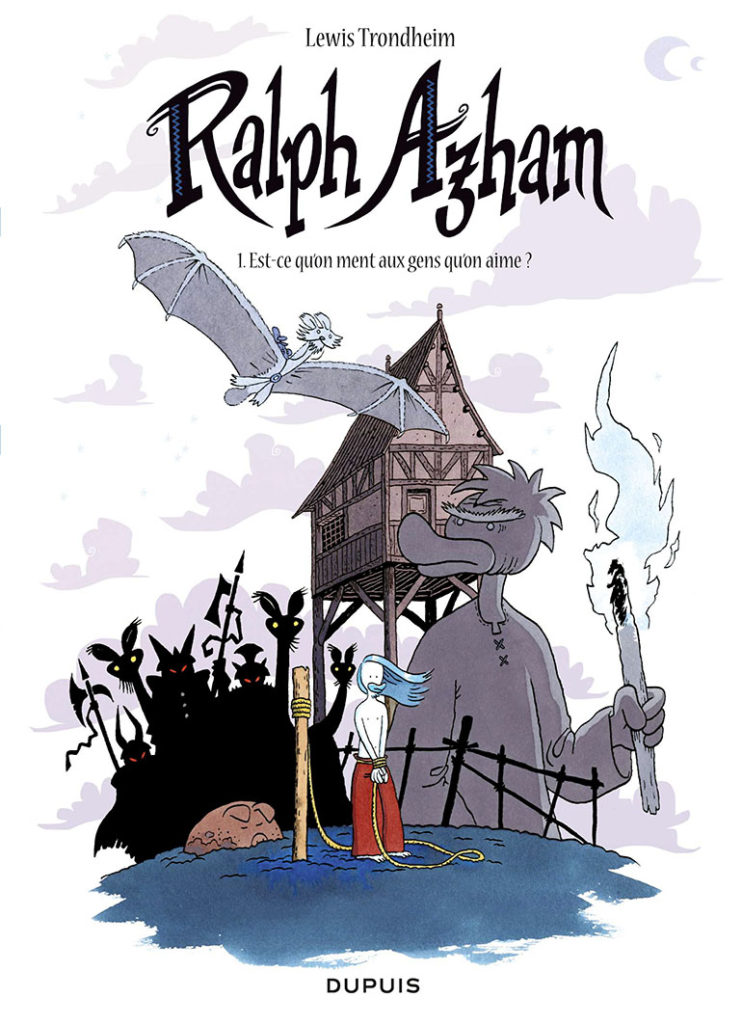

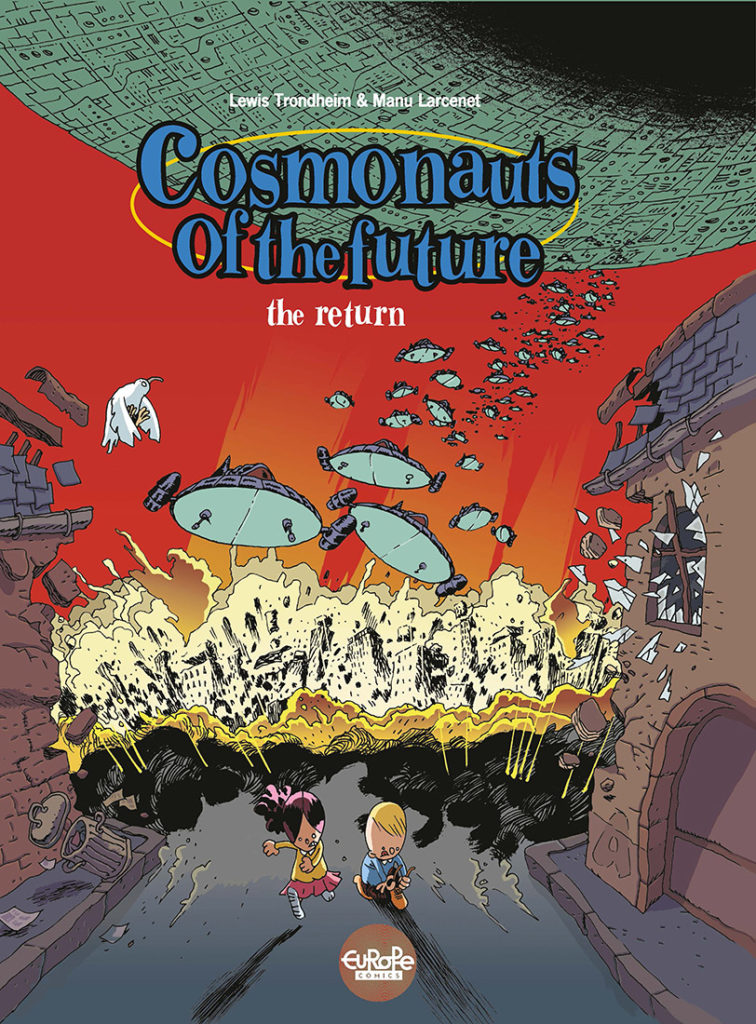

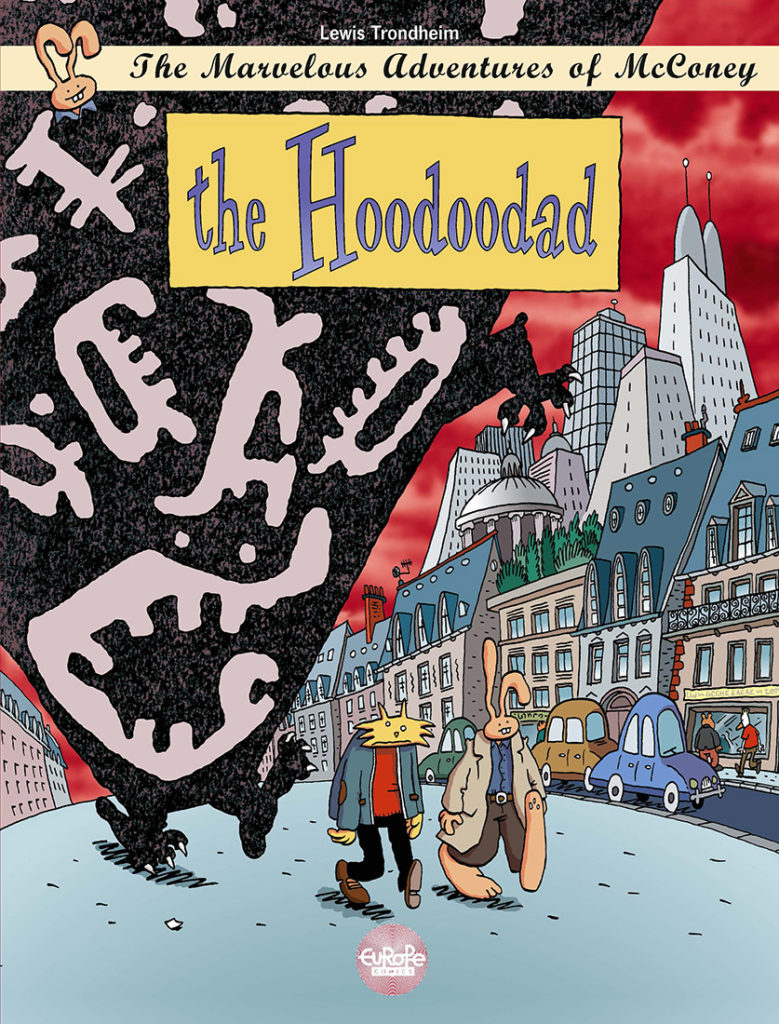

Following some further Lapinot tales and persistent hustling of publishers, in 1994 Lewis, now a papa, signed up with Dargaud, the original publishers of Asterix and about as mainstream as BD gets. A year later he put his buck-toothed bunny into standard colour hardback albums, recognition that both his writing and drawing were ready for mass exposure. Lapinot proved a hit, so much so that in 1997 Fantagraphics tried launching him onto the American market, rechristened McConey. In true Trondheimian manner, both the period genre spoof Harum Scarum and the present day comedy of manners The Hoodoodad start out with a wacky springboard – a scientist mutating mice into monsters, an ancient cursed stone that brings bad luck – and escalate it to absurdity, all the while mixing in the quickfire banter and crazy goofs of his recurring players. Not since Franquin with Gaston La Gaffe and Goscinny & Uderzo with Asterix had anyone so totally reinvigorated the Francophone all-ages comedy adventure tradition, but sadly the first two translations failed to click with American comic shop readers. The good news, though, is that plucky NBM picked up the gauntlet and ran more McConey antics in their bi-monthly comic book Oddballz in 2002. You also get the chance to eavesdrop on the skewed yet strangely sane worldview of two precocious kid geniuses convinced that the world is run by robots and aliens, in Astronauts Of The Future, written by Trondheim for artist Manu Larcenet.

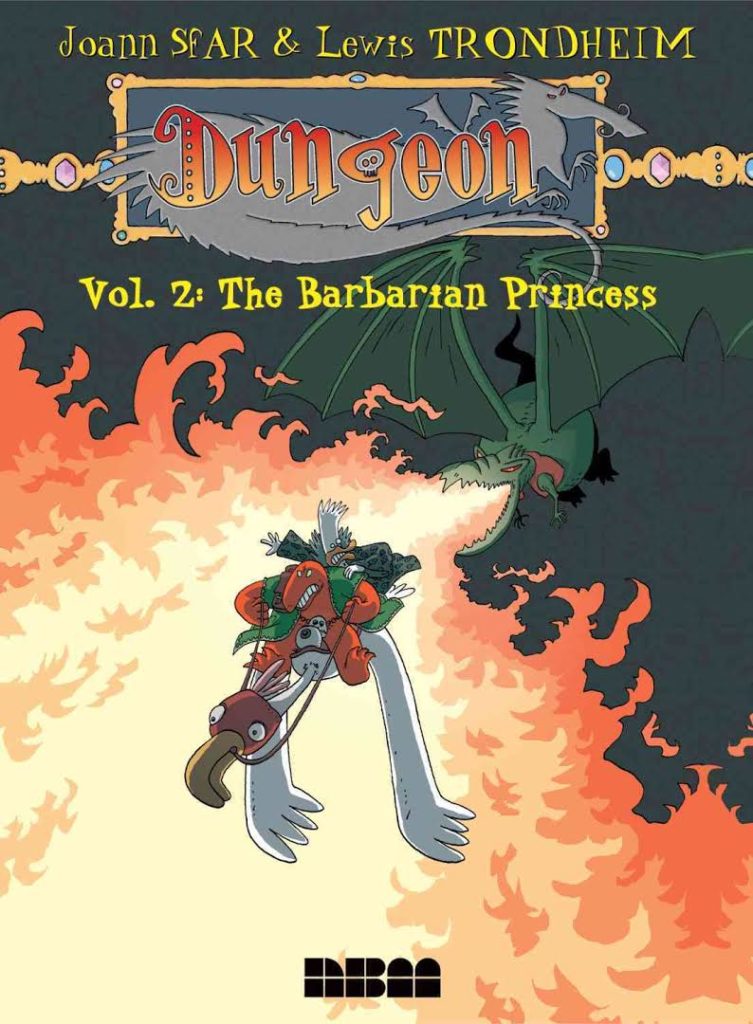

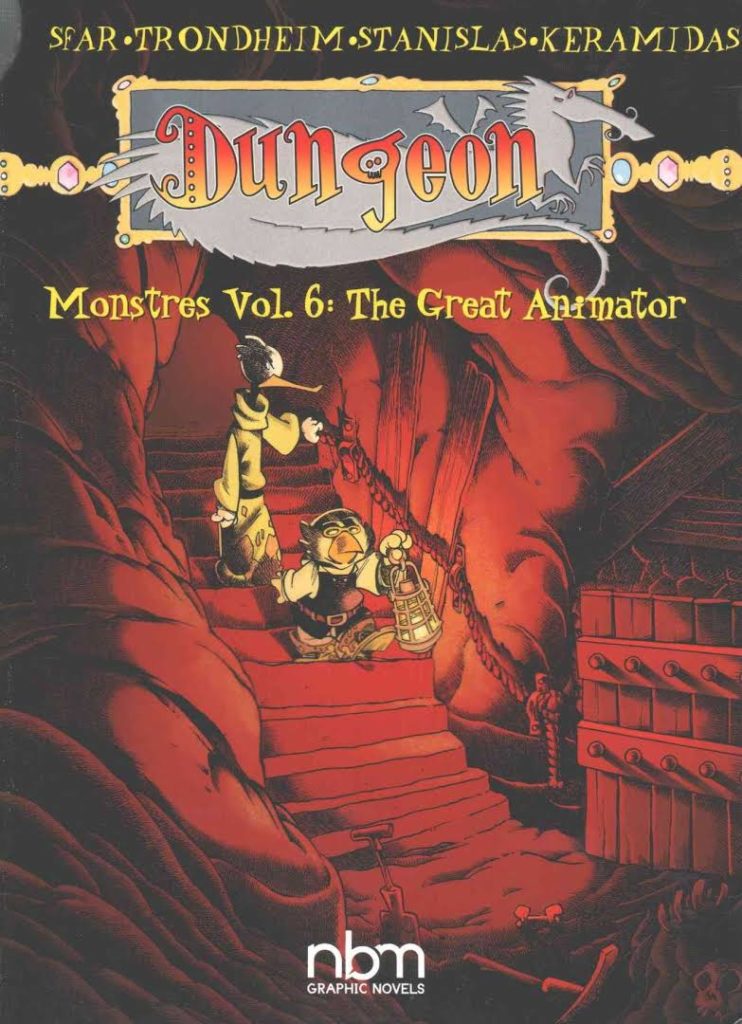

Since Lapinot, the exponential escalation that is at the heart of so much of Trondheim’s humour has also occurred in his own burgeoning, almost profligate output. He can’t seem to stop going forth and multiplying albums for various mainstream publishing houses, whether solo or in collaboration with other writers or artists, roping in his own family, with colouring by his wife Brigitte and even contributions from his kids. The most ludicrously expansive of these is Donjon with the equally fertile Joann Sfar, now being translated as Dungeon in a second NBM comic book. Its French publishers, Delcourt, have made a speciality of lavishly painted and portentous heroic fantasy sagas. Like naughty schoolboys, partners Trondheim and Sfar slyly lampoon this overplayed genre, while reinventing and reveling in all its trappings of wizards, monsters and arcane nonsense, thrusting a luckless duck into the unwelcome role of barbarian warrior on a deadly mission. By conjuring up more and more backstories and future histories, illustrated by further cohorts from Menu to Dave ‘Weasel’ Cooper, they are envisaging a lunatic 297 albums in all. You can either try to make sense of it all, like a good Dungeons & Dragons groupie, or go along for the wild ride of two unfettered imaginations.

Frankly, the multifaceted, ever-expanding Trondheimverse is vast enough to fill a whole line of comic books. Busier and busier with big-time projects, you might expect him to have never looked back, but he has maintained a strong bond and frequent projects for the small press he sprang from, and particularly for the L’Association group he helped found. Their anthology Lapin (or ‘rabbit’, named of course by Lewis) and other indie titles are the sources for all the eclectic contents of the six issues, so far, of The Nimrod, Fantagraphics’ umbrella comic book started in 1998. To my taste these showcase him at his most free and inventive.

In complete contrast to his wordy, word-based Psychanalyse, he has found his metier in the silent ‘pantomime’ strip, from his witty colour Cosmonaut one-pagers (also in Zero Zero) and stitch-inducingly hilarious farces starring his little egg-shaped everypersons, to the tiny devilish one-upmanship of Diablotus and the 120-page masterpiece La Mouche, life from a baby fly’s perspective, which he helped adapt into TV cartoons from 1997. Of these wordless picture-stories, his 90-panel, six-page comedy of embarrassment in the first Nimrod makes me cry with laughter every time I watch his polite visitor to a stately home, kept in a waiting room, grow increasingly fraught, as his every attempt to restore order, from correcting the slightest droop of a flower, only triggers some worse calamity. Another gem follows a flatulent businessman whose ‘trumpet involuntary’ ends up jet-propelling him into his office. This is sublime slapstick animated by the reader, delighting in every little spot-the-difference change from one ticking panel to the next. Like a mime performance, the white-faced actor’s every motion and emotion make him seem to live, trapped inside these butting boxes. Trondheim’s delicate doodles and stick-figure arms and legs make it look so relaxed and so infectiously endearing, it makes you want to draw one yourself. With similar limited means, Trondheim contributed one of his strip experiments, a grid that can be read in various directions and still make sense, to Spiegelman and Mouly’s second Little Lit compendium for kids.

Lewis’s humour thrives on escalation, improvisation, experimentation and keeping his work spontaneous, re-drawing whole albums for new editions, re-drawing The Nimrod‘s logo design every issue. He did this, for example, for Genesis Apocalypso, short stories in which he starts each time from the Biblical black void and then chronicles mankind’s various ‘progresses’, full circle to another black void. Sinister black panels also begin and end three atypically paranoid nightmares, drawn in a very different brush shorthand. His single-page ‘Ineffables’ play with spurious folktale wisdom, usually closing with an ironic sting. His other characters include Kaput & Zosky, stupid planet-conquering alien bullies, and Dud & Dull, a Laurel & Hardy-style knockabout duo.

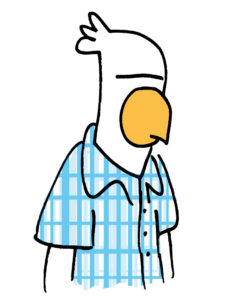

But perhaps his greatest character is himself. He sports a bird’s head disguise, his deepset eyes only rarely peeking out beneath the sort of thick eyebrows sported by Sam the Eagle in The Muppets. As a funny animal, he can even draw himself into the Western Lapinot album Blacktown as a corrupt sherriff. Trondheim first dabbled with his spiky, self-mocking form of autobiography in two pages for Logique de Guerre Comix from L’Association in November 1990. But when Editions Cornelius offered him a quarterly comic in 1993 to fill with twenty four pages of whatever he wanted, he fixed on portraying his life and inner worlds, a first-person approach that surprisingly few French BD auteurs had explored up to that time. His six-part series Approximate Continuum Comics was then collected as an album in 1995 entitled Approximativement, as in ‘Approximately’, an apt title for the distortions and fictions of memory. The opening chapter was the main course in The Nimrod #1 and a later 11-page extract appeared in the Expo 2000 Anthology. Finally, the second chapter arrived in 2001’s The Nimrod #6.

Fortunately this issue is a strong stand-alone story and a good ‘jumping on point’, as the marketing guys say. Trondheim reveals more of the self-doubts and foibles of a struggling cartoonist, husband, father and grouchy, contradictory person, in a freewheeling flow of family life and friends, and of the craft and graft of cartooning. His dialogue and pacing are pin-sharp and no one, except maybe Julie Doucet, can detail the clutter of a cartoonist’s studio so lovingly. Trondheim enjoys surprising himself. The sheer freedom and unlimited budget of comics allows him at any moment to detour on some mad, comedic tangent. All of he sudden he can be expounding shrill opinions on America and Americans or imagining himself as a wildly popular superstar. Sometimes all he needs is one wacky panel, the way ideas pop into your head and out again, reminding me of that fleeting shot of Marianne Sagebrecht momentarily imagining herself in a cooking-pot in Percy Adlon’s film Bagdad Café.

Then in a longer side story, Lewis introduces us to his childhood ‘chick’ self in an unflattering confessional about his part in terrorizing a kid at summer camp with ‘Exorcist’-style pranks. This offers a way for him to analyze his feelings of guilt, and of mischievous glee, at duping the gullible. In the French comics magazine 9eme Art in 1996, he commented on the potential benefits of attempting to come to terms with oneself through autobiography. ‘Revealing myself like this is partly an attempt to understand better who I am and how I behave, so that I can try to iron out my faults. The act of writing about things clarifies them for me… I think that yes, I understand myself a little better now, but as the Johnny Halliday song goes, “A man doesn’t change, a man just gets older…”.’

It’s hard to imagine this hyperactive one-man ‘House of Ideas’ cartoonist ever facing ‘cartoonist’s block’. But sometimes his muse does desert him, as he recalled in 9eme Art: ‘At one point, I was sat at my drawing table not knowing what to do. And at the same time I started drawing myself at my drawing table not knowing what to do, …and, of course, when I was drawing, I was no longer doing nothing.’ So he was able to turn even the gaping void of a blank sheet of paper into a creative spark. This appears in a scene in The Nimrod #6, in which he chastises himself for being such a procrastinator, unable to resist the distractions of playing a dumb computer game or traumatising a pigeon.

Not that he uses autobiography for more candid self-flagellation; you won’t find Justin Green penis-fingers or Joe Matt semen stains here. Trondheim did admit once to Les Inrockuptibles magazine, ‘I have already produced some more personal comics pages, about very private things, but they have stayed in my drawers or I’ve torn them up. I needed to express them, but they’re just for me.’ Trondheim was raised as a good Catholic boy and his personal discretion, his ‘Fontainebleau petit-bourgeois morality’ as he put it, inhibits him from giving a lot of himself away to people, in his comics, and perhaps in real life too. Lewis Trondheim, after all, is not his real name.

As he now charges into his second decade of dizzying productivity, it might appear that he has put autobiography aside, apart from two new L’il Lewis flashbacks in Measles, which confirm how perceptively he can write about the bittersweet realisations of growing up. But it turns out that Trondheim can’t stop himself and he has been recording his daily life by keeping freeform cartoon journals. This year L’Association are publishing the first of these diaries from his trip to a comics festival on the Reunion island, published just as he produced it, no pencils, no whiteout, no spellchecking. This is pure, unfiltered Trondheim: comics as handwriting, comics as natural and sustaining as breathing, comics as spontaneous as living.

On a closing note, I’ll admit the choice of The Nimrod as a title baffled me and many others, until translator Kim Thompson put us out of our misery by revealing that it was simply an anagram of Trondheim’s name. That led me to dabble with Lewis Trondheim’s whole name and I can’t help feeling that, despite what he says, it is more than mere coincidence that Lewis Trondheim is an anagram of ‘The World Is Mine!’ After all, today he’s conquering the Francophone BD market, so tomorrow, why not the world? And, in case you were wondering, he could have called himself Homer Wildstein, or Mildrew Oneshit, or Heidi Lentworms, or I. Wild He-Monster, or Hermione St. Wild, or Nerd Slimeworth, or…

By Paul Gravett, London-based journalist, curator, writer and broadcaster, author of Mangasia: The Difinitive Guide to Asian Comics, Graphic Novels: Everything You Need to Know, Comics Art, Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics and 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die

Header image: The Marvelous Adventures of McConey © Lewis Trondheim / Dargaud