Part of our #ComicsStudies series, this article talks about the French censorship applied to post-war Belgian comics.

Disclaimer: This article contains content potentially unsuitable for younger readers.

The French censorship committee left its indelible mark on Belgian comics throughout the 1950s and ‘60s. Scenes bearing the slightest hint of violence were targeted, comic book heroes’ motivations were put under the microscope, and female characters were relegated to roles of little substance. The biggest Belgian series were established in this very era. To survive, and thrive, they inevitably resorted to self-censorship. The result? Cowboys could not pull any triggers, police could only be portrayed in a favorable light, and bright-eyed optimism was the name of the game.

The heirs

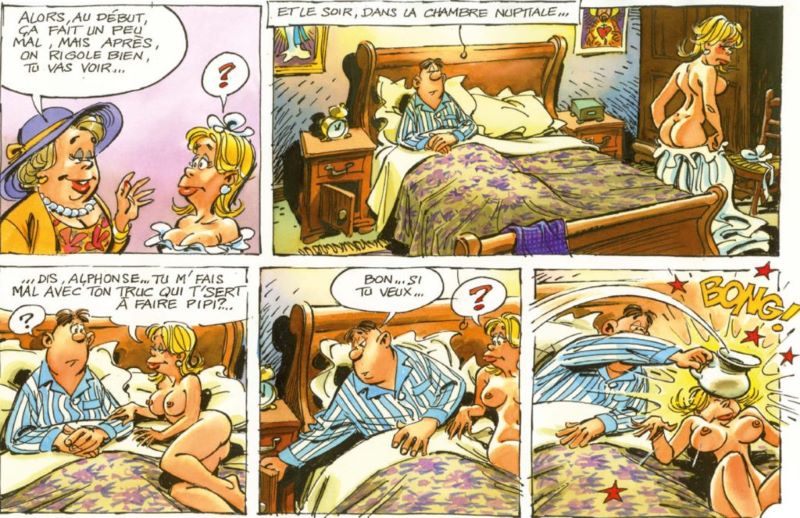

You would think that this kind of mentality would disappear over the years. Not quite… In 2006, as part of a collaborative awareness-raising campaign on violence against women, sketches by Dany (Olivier Rameau, Ça vous intéresse?) were rejected by the French-speaking Belgian wing of Amnesty International. The sketch features a wedding taking place in a church. One of the attendees takes the bride aside and asks her if she’s managed a peek at her future husband’s “toy,” referring to it as “the thing he uses to go pee-pee.” As their wedding night arrives, the new bride asks her husband to give it to her with “the thing he uses to go pee-pee,” and he subsequently smashes a chamber pot over her head. The reaction was immediate: “way too sexist.” Dany protested the censorship and had the support of 30 other authors who participated in the project, including Lucien De Gieter, André Geerts, Hermann, Janry, Marvano and Séraphine.

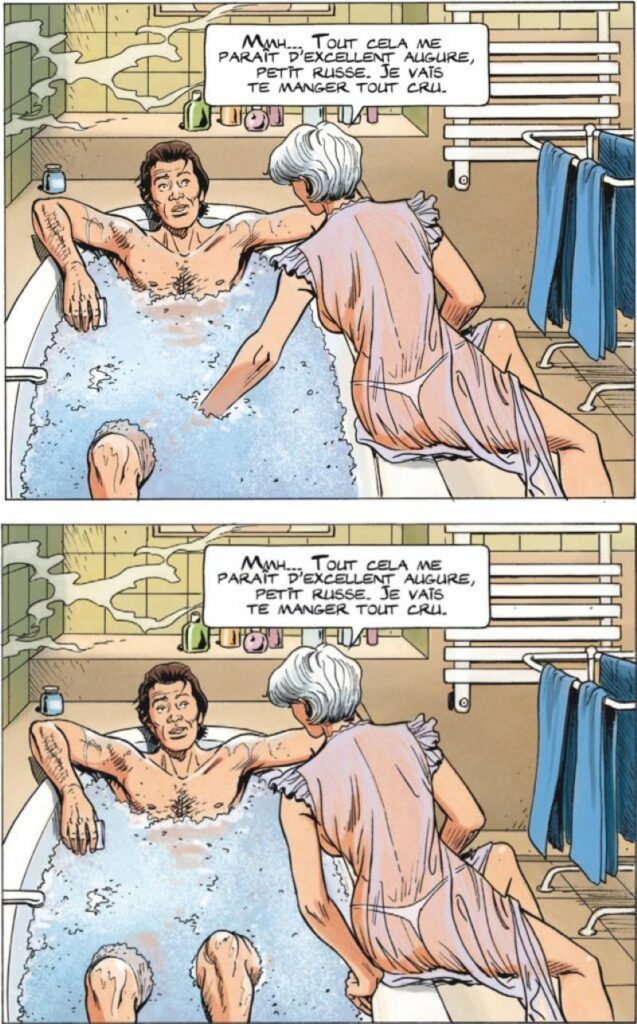

Even nowadays, some scenes are toned down before being published in Spirou to avoid causing distress to sensitive young readers. As recently as 2012, the editorial board asked Philippe Aymond, the artist working on Lady S, to redraw a scene in the magazine’s eighth volume, in which a middle-aged woman, sitting on the edge of a bathtub, slides her hand under the bubbles towards the private parts of a much younger man. In the end, the original version of the scene was kept only in the full-length album. “To be fair, this only ever happened to me once or twice over the span of my six-year-long career,” clarified the editor-in-chief, Frédéric Niffle. “Spirou is a family magazine, for the young and old alike. That’s why we can’t publish Largo Winch: the sex scenes are too explicit, and the stories are often about the economy and other financial matters. For the story to be published in Spirou, that change had to be made. The writers get that now.”

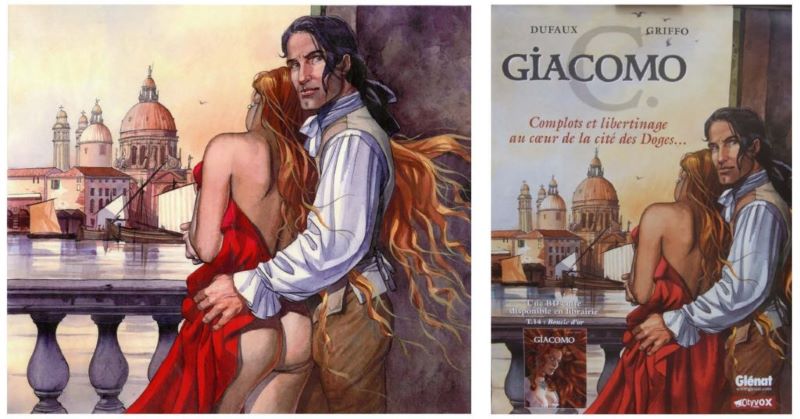

So, did censorship progressively fade over the years? Griffo wouldn’t agree. In 2006, Glénat, his publisher in France, asked him to edit a promotional poster for the launch of the fifteenth volume of Giacomo C. The poster portrayed a sexy young woman next to the hero of the series and was meant to be put up in metro stations and supermarkets. “There was a lot of pressure from the clergy, both Christian and Islamic. In the original sketch, the young woman’s behind is on display, albeit in a subtle way… Still, the poster had to be changed so that the girl’s behind remained chastely out of view.”

Griffo found this sort of interference to be a violation of fundamental freedoms. It meant going back to square one. “In the 1970s, nobody would have batted an eye. But since the ‘90s, we’ve seen reactions like that more and more. It’s as if the whole world suddenly feels the urge to complain. We’re in a different sort of danger these days: the need to be politically correct. For a long time, it was a problem only seen in the United States. Or, at least that’s how it seemed… Now, we’ve all been contaminated! (sighs) If you say something about women, you’re sexist. If you say something about black people, you’re racist. Come on! These days, if you use the image of a woman for advertising purposes, the radical feminist groups are all over you!”

Even children’s comics have a target on their backs, in this case because of parents. In 2010, Ballon Media, publisher of the children’s series Jommeke (Jeremy), received a complaint from a reader over the last scene in Savooien op de Galagapos (Kale on the Galápagos). Gil and Jo are sitting next to a bronze statue at the Antwerp Zoo. The image shows a bust of Charles Darwin, next to a statue of a naked woman whose breasts—and nipples—are very much on display. The anonymous Dutch reader was outraged: “Absolutely not acceptable in a children’s comic!”

Another new phenomenon, which emerged in early 2012, is censorship from the heirs of comics grand masters. Gringos Locos, by French writer Yann and his compatriot, the artist Olivier Schwartz, was hailed as the comic book of the year. It recounts the legendary journey that Jijé, Franquin and Morris embarked on through Mexico and the US in 1948. It was strongly opposed, however, by Jijé’s and Franquin’s heirs, causing a months-long hold on the publication of the book. It was finally authorized to be published with a generous (albeit vague) right of reply by the Gillain family. This all happened despite Yann’s gathering meticulous records via communication directly with the estates of the respective authors. He had not only compiled old interviews by the grand masters, but also enjoyed Franquin’s support who had, in his lifetime, declared “that he would really like to see the journey in comic book form.” “They forgot it was fiction,” Yann explained. “Yes, the volume is based on a true story, but the events are exaggerated for the sake of the narrative. They didn’t get it. The only one who understood our approach was Morris’s widow.” With all this controversy surrounding the book, Yann not only put off writing a sequel, he also expressed ambivalence about completing similar volumes on other grand masters such as Peyo and Vandersteen, as he had originally intended.

Today’s (foreign) censorship

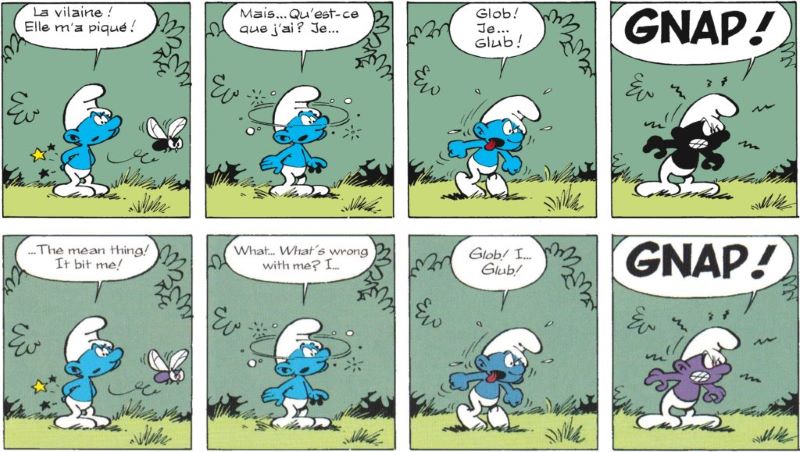

Censorship these days tends be imposed from abroad. Not so much from France, but from the other side of the Atlantic. Differing customs and traditions, as well as a particularly developed sense of political correctness, have often given rise to odd and/or ridiculous impulses to censor. One example was the refusal to publish Peyo’s Les Schtroumpfs noirs (literally: The Black Smurfs) (1959) in the US due to the title. Spurred by their own epidemic of political correctness, the Americans found the notion of black Smurfs to be a little too aggressive—setting aside the implications of hinting at African Americans in this way—and decided that the Smurfs should come in another color, preferably one with less political baggage. Why not purple? And so, in Anglo-Saxon countries, it’s the purple Smurfs who chase their blue peers around. Even Schleich’s famous Black Smurf figurines were banned in the US. As a result, Americans who visit Belgium (or Europe for that matter) buy them en masse. The “Schlips” (Swoofs) of the Cosmoschtroumpf (Astrosmurfs) suffered a similar fate. When Papa Smurf conjured brown, long-haired Smurfs, their color was changed to green for the American market.

The fever of US political correctness goes on. European comics—including those from Belgium—must go through a sort of trial before they can be published in the States. A few years ago, Rosinski was asked by his American publisher to cover up Kriss de Valnor’s chest in Thorgal’s Les Archers. “I put a little blouse on her. I thought, if that’s all it takes to make them happy, why not?” But that was just the start! In L’Île des mers glacées (The Island of Frozen Seas), another volume in the series, a couple of kids use rocks to kill an arctic hare. “It was absolutely horrifying to the Americans,” Rosinski said. “A scene of intolerable cruelty. Never mind that there’s fighting and killing throughout the series,” added Rosinski, slightly offended. “Of course, you always have to be politically correct in the US,” says fellow artist Hermann. “Sarcasm and irony don’t go down well either. You’re not allowed to mock people, and religions even less so. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what I love doing! (laughs)” Murena’s artist, Delaby, also had trouble with the US versions of his series. “In the US, my books can only be sold wrapped in plastic, as if it were porn. They took out every nude from the first two editions. Even when it was just a statue of Mercury! That’s incredibly hypocritical, if you ask me, from a country that’s the world’s largest producer of porn and violence.”

Belgian humor always seems to be causing trouble. In 2010, while the Flemish artist Nix had no trouble exporting his particular brand of humor in the form of the two little rascals, Kinky and Cosy, to France, his American publisher, NBM, was not quite as receptive. “Some countries still put the content warning sticker on the cover of my volumes,” said Nix. “Humor and how much of it people can take definitely varies abroad. You could say we’re super lucky in Belgium. Practically everything is allowed here, whereas in America, I suspect they think I’m some sort of a racist pervert. A joke that could appear in the paper or on TV without being a big deal here would shock the average American. That brings me to a funny story about my American publisher. He called me one day, and said: ‘IfI publish this joke, I’ll be in jail tomorrow!” It was a story about a guy auctioning off prosthetic arms. Fifty euros, anybody? No? Thirty euros, then? Twenty? Fine! I’ll just throw them out… In the last frame, you see a poor guy without arms who’s dying to buy them, but obviously can’t put in a bid (smiles). That sort of joke would never fly over there. Jokes that are implicitly or explicitly about sex are also off limits. Sometimes, Kinky and Cosy hear strange noises coming from their parents’ bedroom. That’s the kind of innuendo you’re better off staying clear of in the US.”

In 2001, Pieter De Poortere published an English version of his silent comic book Boerke, renamed Dickie for the occasion. To secure a place in the prestigious catalog of the great American distributor Previews, the cover had to be changed twice, otherwise it was in danger of ending up in the porn section. “In the first version of the cover, you see a cow urinating milk, but the Americans thought it was a cow masturbating (laughs). I still don’t get how they came up with that… In the second version, I turned the cow around so that the udders were no longer visible, but they still didn’t like it. Finally, in the third version, I stuck the cow in a toilet cubicle, and apparently that was fine.”

A new brand of censorship arrives

A big new problem has made itself known: comic books that twenty or thirty years ago would have been published without any problems suddenly find themselves mired in controversy. The cause tends to be quite sad, triggered by tragic national or even regional events, which is what happened in Belgium. In the mid-1980s, Le Déclic (Click!)—certainly one of the more erotic works of the Italian Milo Manara—was sold without any issue across bookstores in Belgium. In the mid-1990s, however, the country was shaken by the Dutroux affair. Marc Dutroux, a pedophile and serial murderer, had kidnapped six young girls of which only two survived. The case hit the headlines all over the world. Dutroux’s arrest in 1996, and the lengthy trial that followed, deeply traumatized the whole of Belgian society and changed their awareness of pedophiles and their rings, real or imaginary. Even more so a few years later when a new case of pedophilia within the Belgian Catholic church was brought to light. It was a major scandal. Not surprising then that in 2011, when the very popular Flemish women’s magazine Goedele offered Le Déclic (Click!) as an extra supplement, it was three pages short of the original version. The excerpt that was cut featured a mother masturbating her teenage son on a packed beach, while another woman tries to fellate him. “Obviously, there were elements of both pedophilia as well as incest in the scene. We couldn’t leave it as it was,” said Danny Illegems, the then editor-in-chief, in his defense. Oddly enough, the guilty excerpt hadn’t shocked anyone in Belgium when it was first published in book format. Yet, it should be noted that Manara himself didn’t have a problem with the abridged version. In any case, he said, Le Déclic (Click!) was supposed to be more of a comedy than an erotic story. “The publisher made a very wise decision,” he agreed.

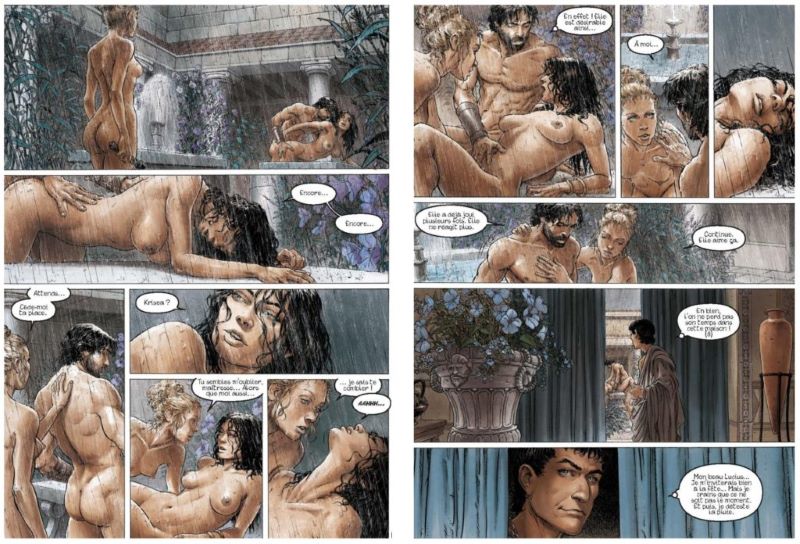

A similar, albeit slightly different case occurred in 2013 with the Murena volume titled Les Épines (The Thorns). Adopting a realistic approach to the series, artist Philippe Delaby and writer Jean Dufaux had wanted to show ancient Rome as it really was. No subject went unexamined: homosexuality, the bloody arenas, sodomy, crime, the values of the era. All in the name of historical accuracy. Eight volumes went to print unscathed but the ninth volume hit a snag when editor Dargaud asked the creators to shorten a lengthy erotic scene. Delaby found nothing shocking about the scene in question, but acquiesced to his editor’s request. “It turns out that four pages of passionate eroticism offend, whereas two do not,” he said. “The editor was worried about a potential backlash, so we gave in.” That said, Delaby saw the move as taking a “precaution” rather than applying “censorship.” In the end, he more or less managed to have the last word: a few months later, Dargaud accepted to publish the complete Murena with a new cover, featuring the uncut version of the scene in question. Was it a publicity stunt or a marketing strategy? Yves Schlirf, publisher at Dargaux Benelux believes that a genre should follow its own rules. “You can even find the series in schools,” he says. And when asked why he then published an uncensored version (without any warning on the cover, no less!), he said: “We can’t completely frustrate the writers either.” The fear of shocking the public is no longer an issue. In the same interview to the Standaard, Schlirf explicitly says: “Up until the late nineties, we had a great deal of freedom in cinema, in literature, in comic books and the theater… Now, I feel a certain sense of prudishness is making a comeback. Pressure groups are popping up all over the place, for example, those huge demonstrations against gay marriage in France. Yet, at the same time, we sell millions of copies of Fifty Shades of Grey. What does it mean? That once again, our morality is overly malleable, changing to suit our needs.”

Online censorship

The most recent kind of censorship takes a totally different angle, and is more American than ever. “Is it acceptable that the Internet is driven exclusively by American values?” Steven Samyn, a political journalist formerly at De Morgen, wondered in 2013. He was outraged when a front page image showing a naked, blood-soaked Syrian child was twice deleted from De Morgen’s Facebook page. His comment reflects the feelings of those in the cultural sector, or more broadly the media. Online experts have long bemoaned the United States’ tendency to inflict their own concept of decency on other countries, to the detriment of those countries’ cultures, laws and freedoms. Comics have been heavily searched online for some time now, which has resulted in clamp-downs imposing absurd regulations, and, ultimately, in cultural hegemony. Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Google… they all want to get their way. One thing’s for sure: measures out of America often turn out to be as hasty as they are poorly thought out. And we can’t help but wonder: in their aim to weed out what they consider to be inappropriate content, have they configured their search engines badly, or is it simply a matter of arrogance?

Asem—a wordless graphic novel by Marc Legendre and Marcel Rouffa—was the first Flemish comic book made available on the iPad, the iPhone and iTunes. Its plot revolved around the lack of understanding—and communication—between young people (of the far right). In 2010, Apple said it was shocked by four pages of explicit sexual content. “How incredibly hypocritical!” commented Johan Stuyck, the publisher at Oogachtend. “There’s just two frames where we can see breasts and two scenes where a naked boy and a girl are cuddling on a sofa, but they’re under a blanket. If that’s sexually explicit, then so is most of literature.” He appealed and, following much debate, the digital version of the publication was finally authorized. The infamous censor bars were not deployed to cover the offending breasts; however, the book is only available for users aged 17 and over. The problem is that Asem was written specifically for young people aged around thirteen or fourteen. “Apple having so much influence over this medium is incredibly scary,” Stuyck explained. “I have an entire backlist that I already know would never be released by Apple. As a publisher, I can’t imagine giving in and bowing down to their kind of censorship.”

Other Belgian comics soon joined Asem in being censored. In 2010, Tom Bouden wanted to offer Het belang van Ernst—his gay adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s classic The Importance of Being Earnest—on iTunes. Apple did not make it easy. Bouden’s occasionally risqué imagery did not go down well, leading them to reply with a testy: Materials that may be considered obscene, pornographic or defamatory are not allowed. The story only received the go-ahead when Bouden agreed to cover the more controversial parts with a bunch of censor bars. Apple has also had less salacious—and therefore more comical—clashes over the years, for example the case concerning the most respectable family in Flanders, who feature in Willy and Wanda (Bob et Bobette). Who would’ve thought that they would be caught on the wrong side of decency? Apparently, Apple did. In 2010, the publisher Johan De Smedt was greatly surprised when he received a warning for possible racial content, following the launch of the mobile app for the publication of the volume titled Anvers et contre tous. The problem turned out to be the use of “black” as an adjective to describe one of the book’s characters: “the Black Lady.” Following endless rounds of discussions, Apple finally admitted that there had been a misunderstanding.

In April 2013, the classics of the French-speaking comic book industry—which had already suffered from censorship in the forties, fifties and sixties—found themselves facing another censorship war. Since the mid-2010s, French digital publisher Izneo had had around four thousand Franco-Belgian titles available online. Apple informed Izneo that several series—including Largo Winch, XIII and even Blake & Mortimer—came under the “adult” category. So you can forget about releasing them on our iPads, said the American company. With great generosity, Apple gave Izneo all of 30 hours to make those titles disappear. Panic stations! After all, what did they mean by “adult” comic books? To be on the safe side, anything that hinted at a breast or could be seen as a suggestive gesture was removed. Izneo initially took 2,800 titles off their list. While some later made a reappearance, the comic book publisher ended up with a pared down list of 2,500 works. To hold this wave of censorship at bay, experts advised the publisher to develop its own reader, much like the Financial Times had already done. In addition to censorship, this would also help circumvent another disadvantage of Apple, namely the oft criticized 30% commission for use of its apps. Since, 2012, the result has been that several large e-book retailers have decided not to collaborate with Apple.

These issues—which clearly go beyond censorship—have nevertheless hit Belgian comic book publishers hard. In early 2012, François Pernot, managing director of Dargaud-Lombard, warned that failing to meet the demands of large multinationals could mean serious problems down the line for the comic book market. Time, he said, was running out. “Europe needs to admit its own weak position when going up against large multinational companies. Clear legislation is our only hope to protect authors and nurture works created locally. […] For many years, powerful lobby groups have been at work in Brussels and their main concern has not been our national pride. I don’t think our representatives across Europe fully grasp just how vulnerable we are. We are a large Belgian company, but we are nothing compared to Apple, Amazon and Google. We need help and protection! Urgently! Amazon is one of my biggest customers. But I don’t want to soon find myself serving them or anybody else. We want to keep our freedom and ensure our group remains strong. For now, this is still the case, but if we want things to remain as they are, I urge you all to get to work before it’s too late…”

Excerpt from La Belgique dessinée, by Geert De Weyer (Ballon Media, 2015).

Translated by Storyline Creatives.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily represent the views of Europe Comics.

Header image: [Cover for “Boerke”] © Pieter de Poortere / Bries, 2003