Part of our #ComicsStudies series, this article talks about the French censorship applied to post-war Belgian comics.

Disclaimer: This article contains content potentially unsuitable for younger readers.

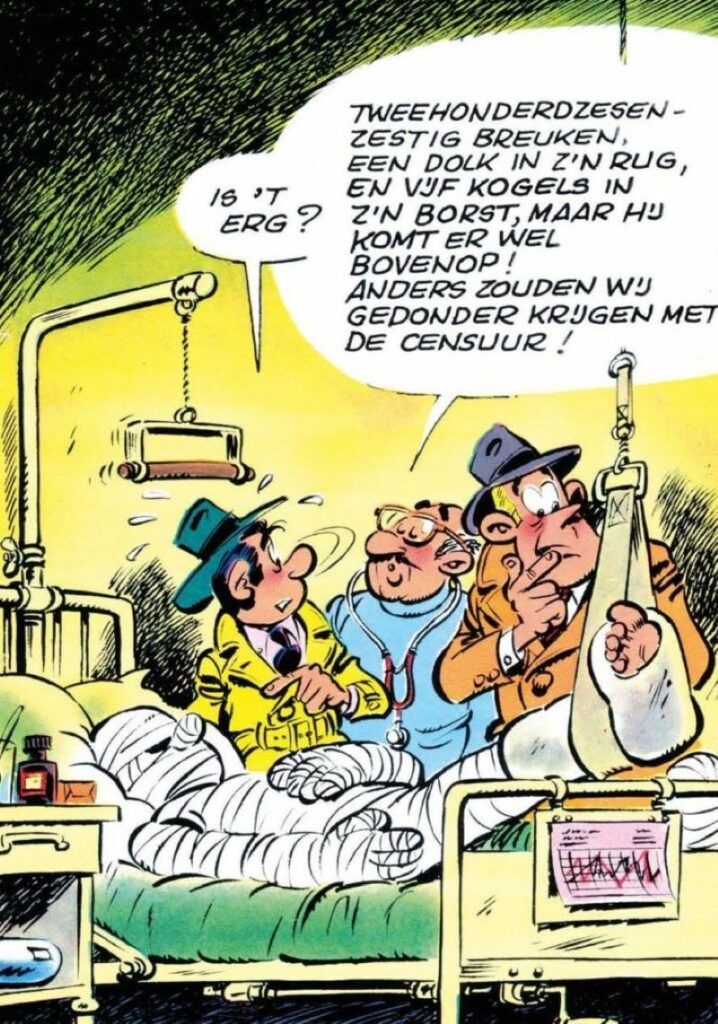

The French censorship committee left its indelible mark on Belgian comics throughout the 1950s and ‘60s. Scenes bearing the slightest hint of violence were targeted, comic book heroes’ motivations were put under the microscope, and female characters were relegated to roles of little substance. The biggest Belgian series were established in this very era. To survive, and thrive, they inevitably resorted to self-censorship. The result? Cowboys could not pull any triggers, police could only be portrayed in a favorable light, and bright-eyed optimism was the name of the game.

The little universe of Belgian comics spent years under the thumb of moronic censorship, courtesy of their French neighbors. There was little room to breathe until, eventually, the censors began to lose their influence—at least enough to allow authors to speak out. Sooner or later, every notable Belgian writer—especially if they were French-speaking—was sure to become a target. External censorship was bad enough, but a worse trend soon emerged, which saw writers censoring themselves, even before their publishers could intervene. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that writers felt a relinquishing of the committee’s iron grip.

In a 1984 interview, Morris, who created the world-famous cowboy Lucky Luke, discussed the reach of decisions that emanated from the French censorship committee, outlining why his volumes contained little to no actual violence. He first cited his own beliefs. “I wanted the comics I created to reach a very wide audience of youth.” The other, more pedestrian, reason was of course the limited freedoms of the time. “Not only could the French veto anything that ran counter to their rules, but they could also exclude whatever they considered as not being in good taste. A concept that could shift from one day to another…”

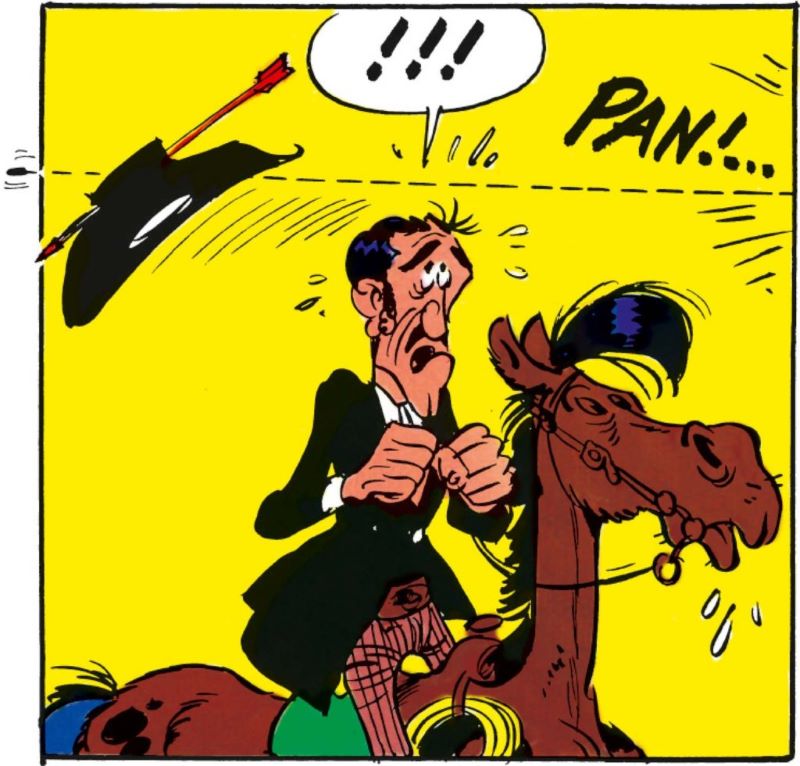

The extent of their reach became clear soon enough! Much like his peers, Morris was painfully aware of the sword of Damocles hanging over his head. And yet, the French authorities often decided his own self-censorship didn’t go far enough. Time and again, he came under fire from the committee as well as his own publisher. Case in point: the initial cover of The Rivals of Painful Gulch (1962) had to be redrawn because a bottle of alcohol was visible in the corner. The ban started with the guns, then warring clans couldn’t do battle, and then violent deaths were disallowed. A western without fights, gunfire and whisky? Morris soon became exasperated… And it came as little surprise when he heard “Are you out of your mind?” from the French when he portrayed Billy the Kid (1962) with his lips around the barrel of a gun in Spirou (in the first ever edition of the volume).

Morris never revealed whether censorship was ultimately the reason he left Dupuis for Pilote (a magazine published by Dargaud). He admitted, however, that “as soon as I was taken on by a French publisher, all my problems disappeared. Censorship was essentially a protectionist measure. They were being twice as harsh with non-French publications. Clearly, they were furious that Spirou and Tintin, the two biggest weekly comics, belonged to the Belgians. So they came down on us with the full force of censorship… The consequences were disastrous: Charles Dupuis was spooked to the point that he became fussier than ever with his own writers. Every piece of submitted work was subject to a sort of pre-censorship.”

The trap

It was a problem for practically every Belgian comic book magazine out there, even more so for big names like Spirou and Tintin. Tibet recounts a revealing episode on this topic, which took place as he was discussing a new story for the Tintin magazine one day with Hergé, the artistic director. It was about a gang of thieves about to make off with everything that was made of gold. “Including gold teeth?” Tibet asked. Hergé was stunned, and his heated reply was, “What’s the matter with you? That’s a ridiculous suggestion, and definitely not suitable for young readers!”

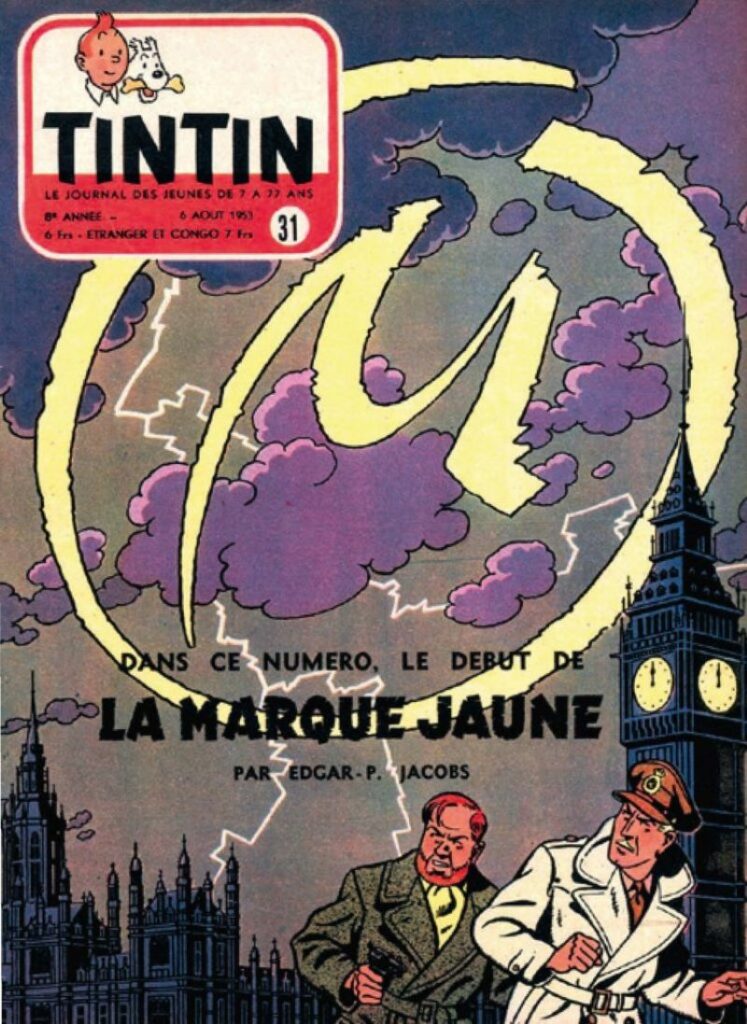

Belgian writers—especially the famous ones—often saw their work under threat of being cut up by the censors. The well-known realistic series Blake and Mortimer by E.P. Jacobs that was featured in Tintin was subject to some pretty odd censorship at times. In 1953, the cover of The Yellow “M” came under serious criticism because one of the characters was shown holding a gun, an image that the Parisian censors deemed to be “inciting violence.” The censors continued to breathe down Jacobs’ neck when he released another volume in the series, Atlantis Mystery (1957), which happened to feature several frightful scenes. Five years later, The Time Trap was also criticized and subsequently banned in France for an entire decade. Its crime had been to portray a dark outlook of the future—including allusions to a Third World War—which was deemed “too shocking” for the audience. Jacobs began to second-guess himself, and doubt whether he had any room to maneuver—and indeed any future. Haunted by the specter of censorship, he created The Necklace Affair, his most innocent, anodyne volume yet, which went on to achieve minimal success.

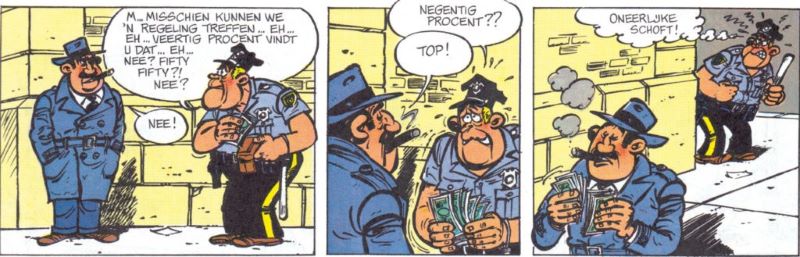

Some censorship decisions made no sense whatsoever. Berck, who left Tintin for Spirou, is still baffled by what happened with The Gorillas and the Dollar King. The eighth volume of the humorous police series Sammy, which had been running since 1972, was banned in France for depicting corrupt American cops. “Our representative in France clarified time and again that it was the American police, not the French, being shown as corrupt,” Berck recalled. “But it was a waste of time. They insisted kids could not be subject to the idea of corrupt cops, no matter where they were. That said, funnily enough, only foreign writers had to justify themselves to the committee. French writers were never put on the spot. Their good credit was guaranteed. Looking back, whatever they were trying to do had little success. Banning the volume just forced booksellers to make the trip across the border and buy it in Belgium. Ultimately, The Gorillas and the Dollar King became the best-selling volume of the series.”

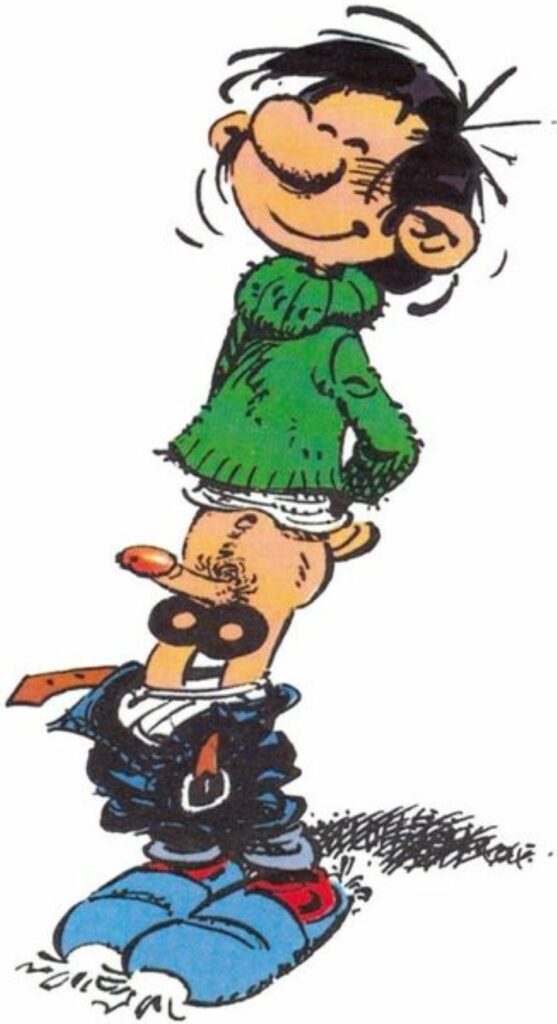

Spirou, the iconic bellboy clad in red, was also subject to his own fair share of deletions, censor bars and cuts. The prepublication of The Rhino’s Horn (1954) saw the villains’ guns disappear. “Not educational,” was the committee’s conclusion. The Marsupilami was next to come under fire by French censorship, concluding: “[it is] an animal that doesn’t exist, has nonsensical proportions and makes incomprehensible noises…” The committee, however, was unable to completely ban the odd beast. A small comfort. In another example, “Le gorille a mauvaise mine” (literally,: “the gorilla looks terrible”), the original title of a Spirou adventure, triggered the wrath of the committee and had to be replaced by “bonne mine.” The title thus became The Gorilla Is in Good Shape. For once, Franquin thought the change that was imposed was a positive one. The original wasn’t a winning title for the gorilla, whereas “bonne mine” showed that the gorilla had friendly intentions.

Franquin also recounts that, for a very long time, cursing wasn’t allowed. It was one of the reasons why so many comic book characters had their own curse words, like Gaston Lagaffe with his famous “M’enfin!” (loosely translated, “What the heck?”). This is also the case with Captain Haddock in Tintin, who came with a veritable thesaurus of insults. He hardly ever walks into a scene without one of his trademark expressions, along the lines of: “iconoclast,” “thunder of Brest,” “ornithorhynchus,” or “freshwater sailor.” “Haddock doesn’t really curse,” Hergé argued. “He uses ordinary words. ‘Ectoplasm’ is not an insult, but the way he says it makes it sound like one.” And in Blake and Mortimer, the heroes stick to the good old “by jove.”

Let’s be frank: up until the mid-1970s, comic book heroes who dared to reveal human weaknesses such as laziness, cowardice, lust or hatred were considered guilty of all wrongdoing. And the same went for any and all signs of criminality, such as theft or merely associating with shady characters.

The Church

If you thought the French censorship committee was the only one passing judgment on Belgian comics, you’d be mistaken. The industry was, to varying extents, influenced by all the important actors of the time. The Belgian Catholic Church was a notable example. The daredevil Tintin was actually revered by the clergy, especially as a good example for youth. On the cover of the Christmas 1948 issue of Tintin magazine, drawn by Hergé, Tintin and his friends are kneeling in prayer to baby Jesus. A bible is in full view by their side. A classic scene that was given a vigorous nod of approval by the Belgian clergy.

It was well known that the Catholic faith knew how to leave their mark on Belgian comics, or, more bluntly, to control what went in them. While French censorship remained a constant factor to take into account, writers were also forced to reckon with controlling agents in their own country: the Catholic authorities, the publishers, and even the printers. The clergy in particular were quick to take any “black sheep” to task! If necessary, they could demand meetings with the paper’s editorial board. Charles Dupuis himself was aided by the family priest, who made sure that religious rules were followed to the letter.

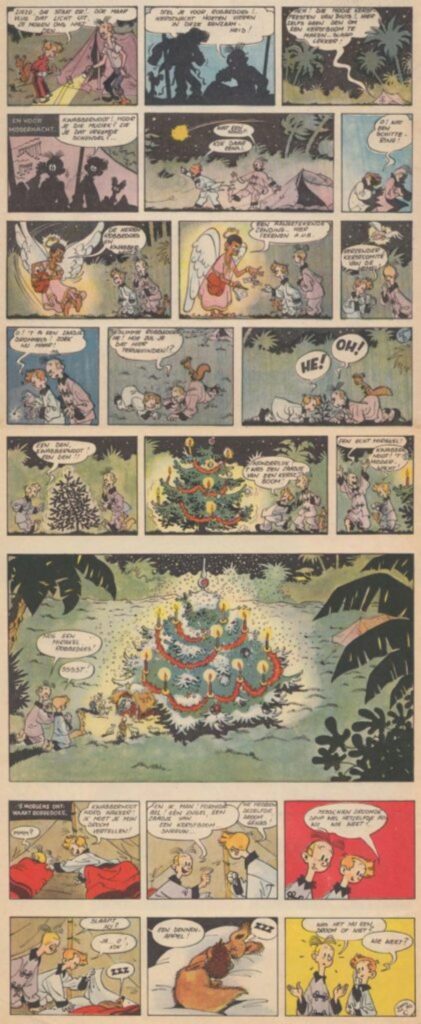

The Church wasn’t to be messed around with, a lesson Franquin learned through one of his short stories for Spirou. “They asked me to mention Christmas on a certain page in one issue. It made no sense, Spirou and Fantasio were in Africa just then, among lions and other animals. I was forced to shoehorn a Christmas tree in there somewhere. Christmas among baobabs… I mean, come on.” Nevertheless, a Christmas miracle was yet again achieved: the comic features an angel all of a sudden tumbling from the sky. He says he’s a messenger from the Christmas committee, sent from heaven with a special delivery containing a seed. The seed falls to the ground and, amazingly, a Christmas tree springs up on the spot. Hallelujah.

Morris had a similar experience. In 1963, the cover of a December issue of Spirou, set to come out just before Christmas, featured a square dance music band, accompanied by Lucky Luke’s harmonica. Charles Dupuis thought it was a nice illustration. Very well drawn… but why was there no hint of Christmas? Morris heaved a large sigh… and gave in. In a later interview, he admitted to sticking a small chapel in the background. And indeed, if you look closely, it’s visible on the back cover between certain characters’ legs.

Prison sentences

In a 25th anniversary tribute issue of Tintin, Greg, who had been the magazine’s editor-in-chief since 1965, expressed his enduring disbelief about a 1971 study on the consequences of the policies of the French censorship committee. Greg wrote that censorship had been practically non-existent in Belgium. He emphasized, however, that “the French censorship more than made up for the absence of censorship in Belgium. By 1971, it had devastated comics. While violence was seen more and more in films, plays, posters or simply in people’s everyday lives, it was completely purged from comics. An 18-year-old could encounter more danger crossing the street than reading a comic book, something the committee was well aware of. It made it all the more difficult to predict what they would take issue with and intervene on.” Greg was critical of the ambiguity of the committee’s decisions. While remaining discreet about the particulars, he told the story of an “odd” incident, a volume published in the mid-1960s that had proved “tricky” to the committee. It is suspected he was referring to Barbarella, an erotic story by Jean-Claude Forest.

“Six or seven years ago, it could not be sold to minors. In France, you could go to jail if certain comics were found in your possession. Even mentioning the names of the writers and editors was punishable. In the meantime, however, the particular volume in question was adapted for the cinema. And movies are not subject to the same rules as comics. The heroine’s name and face was in every movie theater, on giant posters, and even the papers wrote endlessly about the movie without any issue. From print to screen, the characters and the story hadn’t changed one bit. The only thing that was different was the medium. So, the question became: how come the rules that apply to movies and comics differ so much?”

There was a massive fear in the comics industry of losing all autonomy. In 1966, France took its censorship efforts a step further, announcing a new law on publications for young people in Europe. This time, the backlash came from an array of European publishing houses. Rallied by Raymond Leblanc, editor of Tintin, and Georges Dargaud in France, many important European publishers united under Europress-Junior. They essentially followed the example of the Americans and their Comics Code, which was thrown together with some haste when the US government tried to gain control of the content of youth publications. Back in Europe, to stave off outside intervention, as well as criticism, the publishers came together and drew up their own code of conduct. It was a compromise, specifically to mitigate the creativity-blocking effect of general self-censorship that had taken hold of the industry. Instead of countries each following their own set of rules, there was now a code of ethics for all of Europe. “Europress-Junior is for everyone. It is bound, however, by a reasonable level of discipline, which aims to avoid both the lowest common denominator, as well as excessive mawkishness,” wrote Greg. The biggest magazines were already anticipating Europress-Junior’s detailed code. Self-censorship reigned supreme. Even Franquin openly admitted: “I subjected myself to self-censorship again and again in Spirou… I could tell some of the jokes would not make it.” Maybe the grand comic book masters were also a little jealous of the countless new underground comics—launched by artists, scriptwriters and editors—in response to the seemingly permanent state of (self-)censorship. Some publications, for example the French magazines Hara-Kiri and Métal Hurlant, went on to become wildly successful through their use of satire and anarchy to blast the narrow-minded views of the authorities.

Belgian series, European censorship

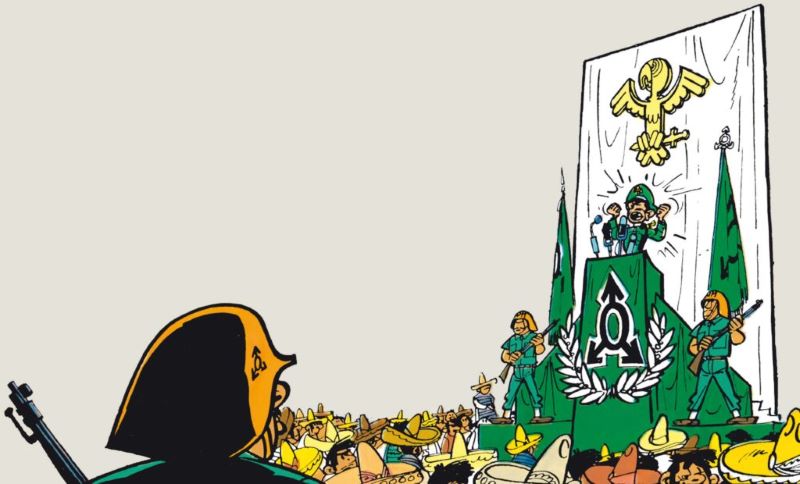

Whether self-imposed or not, censorship prevailed well beyond the borders of France. Franquin’s antimilitarist volume The Dictator and the Mushroom (1956) was banned in Spain until the 1970s. The writer used photographs of Hitler to craft the way in which the dictator spoke, a clear reference to Nazism. He took symbols from the Third Reich as well: the black eagle with spread wings was replaced by a parrot, and the swastika became a circle pierced by an arrow at the top and two others at the bottom. The Spanish dictator Francisco Franco—in power from 1936 until his death in 1975—and his entourage didn’t find a dictator being ridiculed to be particularly funny. In the early 1970s, when Franquin found out that a Greek paper wanted to publish the adventures of Spirou and Fantasio, he asked that they start with this volume, fully aware that Greece was at that moment in history being crushed under the Regime of the Colonels.

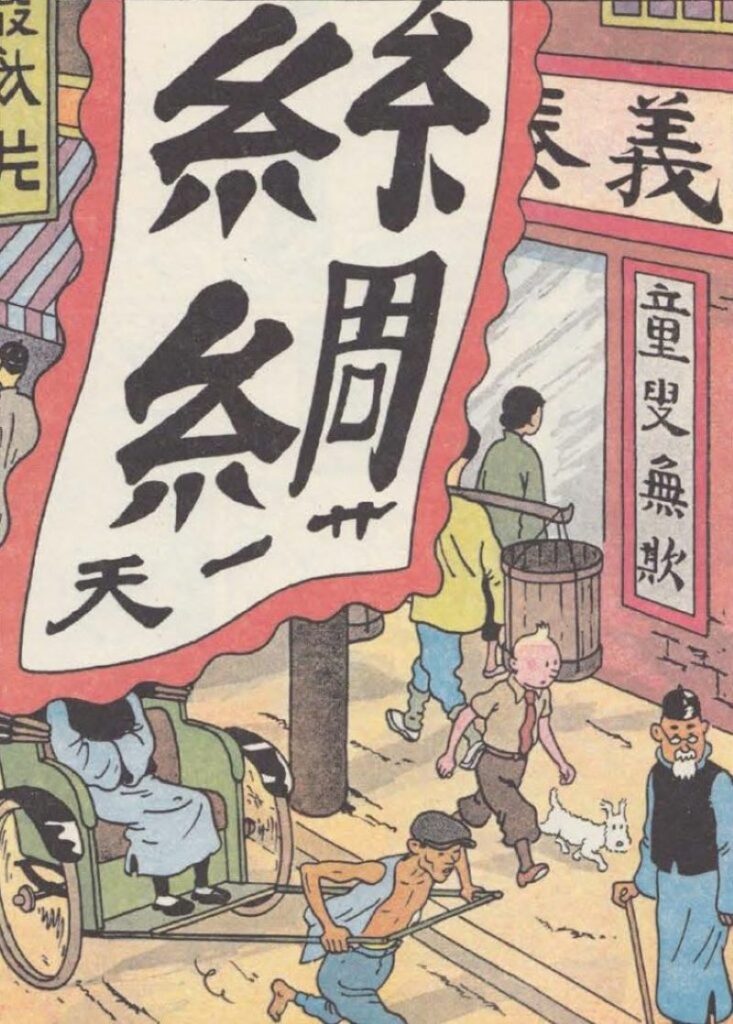

Even Hergé, who was celebrated across Europe for Tintin, often had to compromise to avoid offending certain people or going against certain cultural sensibilities. For example, in the first version of Tintin in the Congo (1930), Tintin literally blows up an enormous rhinoceros. The beast’s demise, implausible as it was, offended the series’ Scandinavian publisher who urged Hergé to draw something else. In the revised edition, the rhinoceros, startled by a gunshot, flees without coming to any harm. For their part, the Nazis banned two Tintin volumes: Tintin in America and The Black Island. Meanwhile, oddly enough, the antifascist message in King Ottokar’s Sceptre in 1938 seems to have gone over their heads. For the Japanese, The Blue Lotus (1934) proved quite unpopular, which was hardly surprising. The Japanese consul in Brussels put up a vigorous protest at the time of its publication in Le Petit Vingtième. In the revised 1946 edition, several sensitive passages were removed, including a lively street scene that featured political slogans such as “Boycott Japanese products” and “Down with imperialism!”

Hergé revealed his tougher side in The Black Island (1937), set in Sussex and the Hebrides. Tintin—a kid-friendly character—is shown pointing a gun at two people and using a cold tone in English to say: “One more step and you’re dead.” In the actual English version, the language is somewhat tempered with the milder “Get back and put up your hands.” When the British translators raised several red flags regarding the text, Hergé dispatched Bob De Moor to Scotland and England, with the task of gathering information for a new edition. Based on De Moor’s notes and sketches, an entirely overhauled and up-to-date third edition was finally published in 1966. In 1969, upon the request of Hergé’s British publisher, a drastically altered third version of Land of Black Gold was published. The publisher had taken issue with outdated references to the conflict between Jews and Arabs, as well as their common fight against the British, who, in the late 1940s were carrying out a UN-mandated mission by occupying Palestine. And so, British troops were replaced by Arab police.

Not all of Hergé’s changes to the adventures of Tintin were dictated by censorship. In fact, a lot of them were carried out to suit his own needs and ambitions. In order to keep Tintin a palatable star across European territories, it was essential to avoid offending or inviting criticism. He also made adaptations driven by a desire to secure Tintin’s universal appeal. For example, the newer version of Tintin in the Congo (1946), which had been renamed Tintin in Africa in Dutch, had multiple references to Belgium and Belgian politics removed. Why? Very simply, Tintin had become famous across Europe, so Hergé decided to remove references that would tie him too closely to one European country, and therefore impede his popularity in others. References to colonization were also taken out, as was the classroom scene where Tintin attempts to instill Belgian-ness in African schoolchildren. It was a lesson that famously began with: “My dear friends, today I have come to speak to you about your motherland: Belgium!” In the revised version, Tintin settles for teaching math, an altogether less politically charged subject. Finally, he no longer leaves from the port of Antwerp to reach Africa (his departure point remains, or rather, becomes a mystery instead). As the story closes, he sets sail not back to Belgium, but back to Europe.

Excerpt from La Belgique dessinée, by Geert De Weyer (Ballon Media, 2015).

Translated by Storyline Creatives.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily represent the views of Europe Comics.

Header image: [Cover of “ça vous intéresse?”, by Dany] © Dany, 1988