The specifically British contribution to the history of comics and cartoons remains under-researched and underappreciated. While there is a growing critical literature on such high-profile figures as Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Grant Morrison, huge swathes of British cartooning history have been neglected by critics, historians, and fans. As James Chapman points out in his informative study, British Comics: A Cultural History, the “work of Martin Barker and Roger Sabin represents the only sustained academic engagement with comics in Britain… the British comic has never achieved the cultural cachet of the bande dessinée, but nor has it found a popular mythology equivalent to the American superhero tradition.”

While Chapman might also have pointed to Paul Gravett and Peter Stanbury’s 2006 book Great British Comics: Ripping Yarns and Wizard Wheezes, his larger point is a valid one. Not only has “scholarly attention” been “thin on the ground,” fan culture in Britain often evinces a greater interest in second-tier Marvel characters than indigenous creators and titles. The so-called “British invasion” of the 1980s and 1990s is the conspicuous exception precisely because it left its mark on the American mainstream.

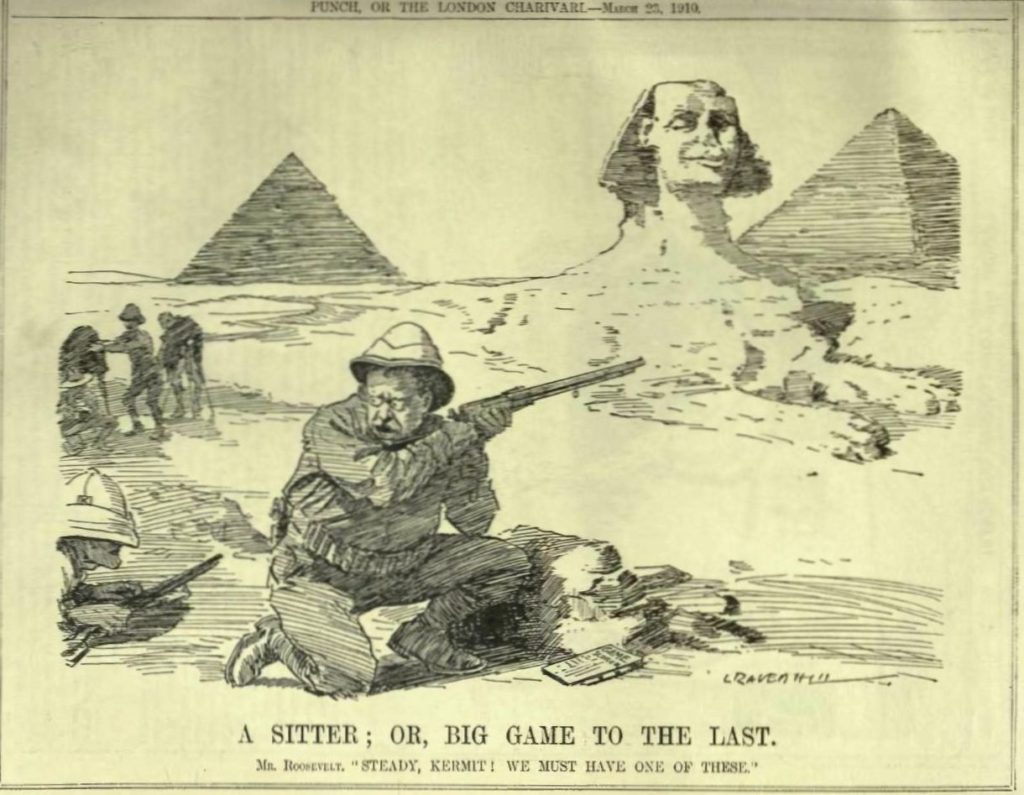

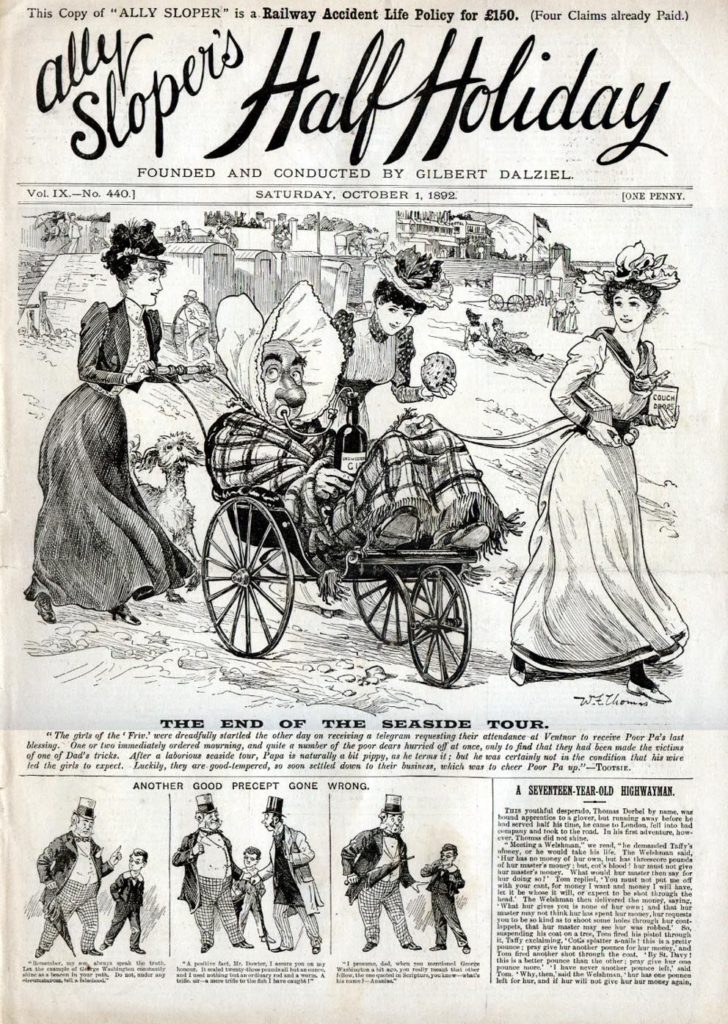

Both the scope and the scale of British cartooning are worth emphasizing. The medium’s early development was profoundly influenced by the work of satirical print artists such as William Hogarth (1697-1764), James Gillray (1757-1815), and George Cruikshank (1792-1878), as well as by various London-based illustrated magazines of the nineteenth century, such as Punch, the Illustrated London News, and Pictorial Times. Another key title, launched in 1884, was Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday, which was “not only the first comic-strip character to feature in his own self-titled magazine but was also the first to generate spin-off merchandising including mugs, watches, postcards, and figures…His admirers included H.G. Wells, who referred to Sloper as ‘the urban John Bull.’” Other prominent comics magazines of the period included Illustrated Chips, Comic Cuts, Boy’s Comic Journal, Scraps, and Tit-Bits, which was not nearly as lewd as its name suggests.

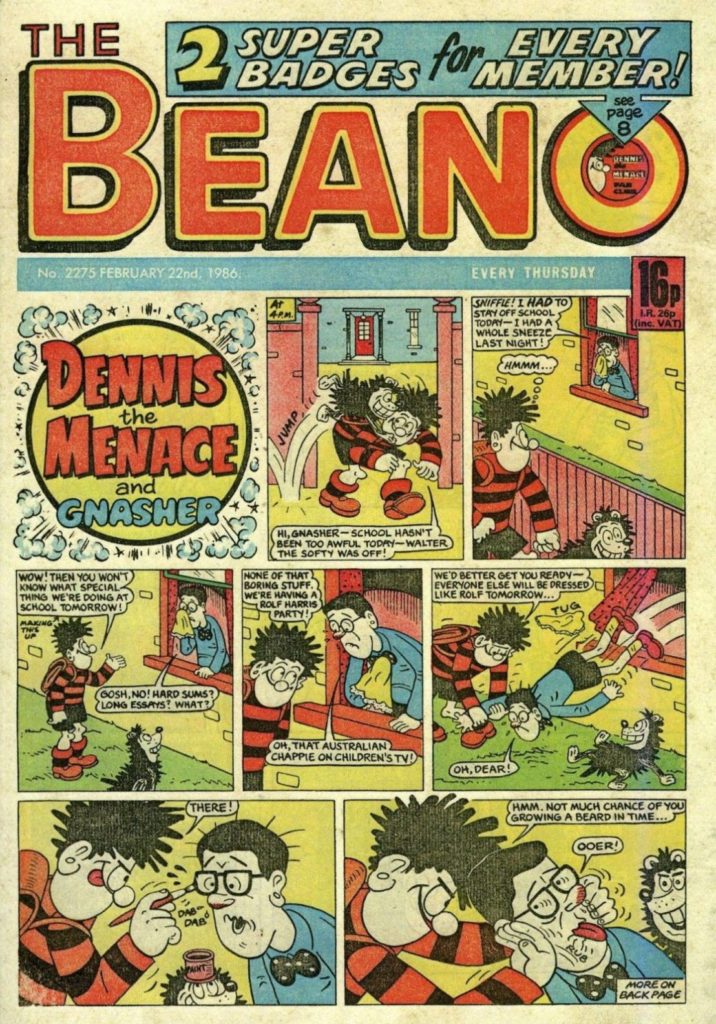

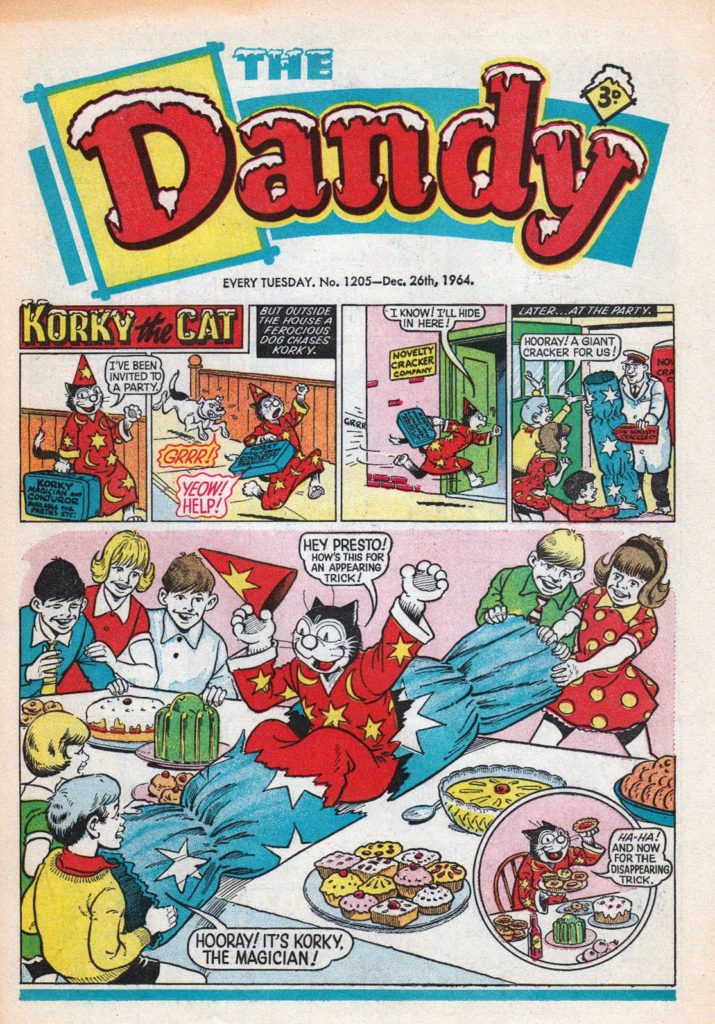

The template for British cartooning was pretty much established by the early years of the twentieth century: while up-market newspapers showcased the satirical imagery of respected editorial cartoonists, the preponderance of comic art appeared in humorous or adventure-oriented weekly or monthly magazines targeted at boys or girls. Comics in Britain primarily came to mean gag cartoons, comic strips, and one-or-two page graphic stories embedded in cheaply printed, comics-filled magazines. These comics were typically short-form, whimsical, and often cheeky, although war comics and related genres also played an important role in the comics marketplace. Even today, most Britons, if pressed to name a “comic,” would probably come up with The Beano (1938-present) or The Dandy (1937-2012) rather than, say, a superhero or crime title.

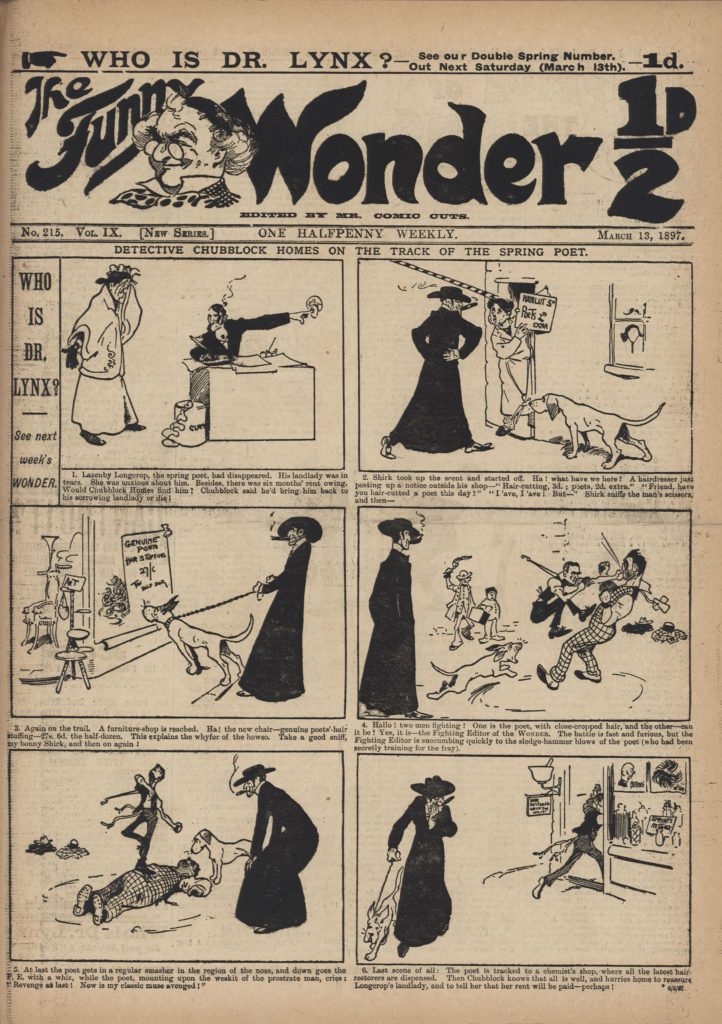

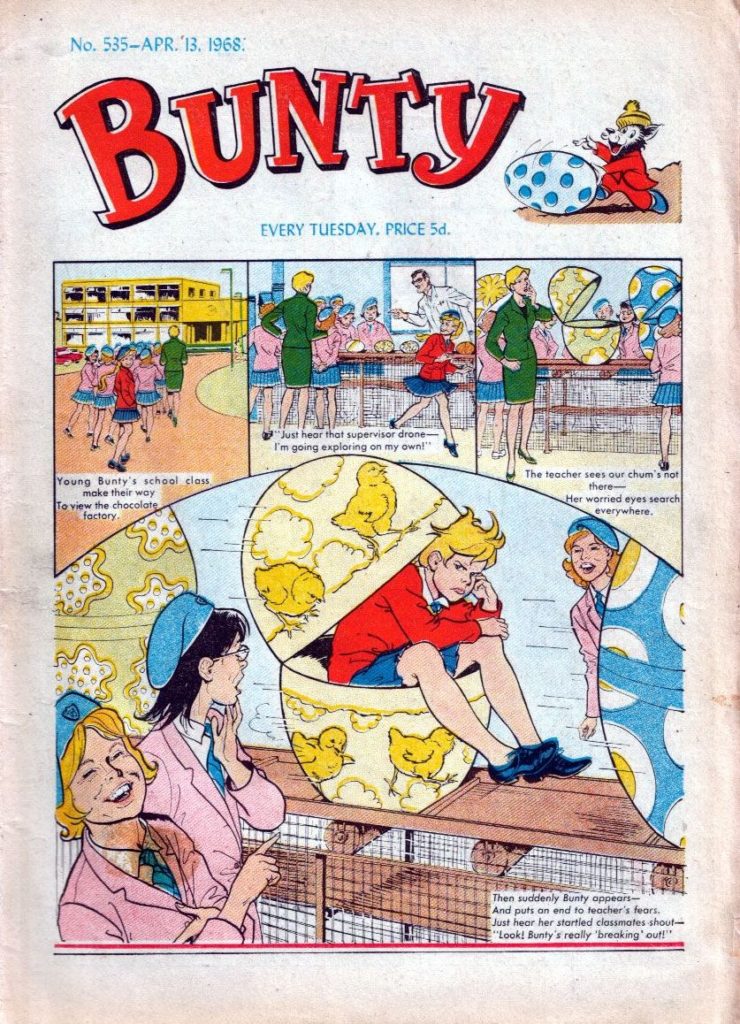

Over time, many publishers began to focus their attention on younger readers, and by the turn of the century there was a profusion of papers and magazines aimed at kids, teens, and young adults that featured cartoons, comic strips, short stories, jokes, and prizes. Representative titles included Funny Wonder, Puck Junior, and various magazines aimed at young children, including Butterfly, Playbox, and Chuckles. There would eventually be a range of illustrated periodicals aimed at girls, such as School Friend, Girls’ Crystal, and Schoolgirls’ Weekly; these are the obvious predecessors to more recent girls’ comics, which include Bunty, Jackie, Mandy, and Girl. The “comics boom of the 1890s,” Chapman reports, led to the consolidation of the “juvenile periodical market” and the emergence of newsstand-friendly titles aimed at various age groups and social classes. The newsstand, rather than the specialist shop, continues to generate the bulk of comics sales in the U.K., and the sheer volume of juvenile, long-forgotten comics magazines that Chapman references is impressive.

Comics like The Beano are quite different from the ones U.S. readers are familiar with. As Chapman says, they “represent a world of social inequalities – tensions between ‘toffs’ and the working classes are a recurrent theme of strips like ‘Lord Snooty’ – and where characters are so impoverished that a plate of ‘grub’ is a desirable reward. They also differ from other comics in that they allow transgression against adults.” Typically organized around one-page graphic stories that feature recurring stock characters, The Beano and others of its ilk favor fantastic plot resolutions rather than fantasy settings, with wiseacre school kids pulling the wool (sometimes literally) over the eyes of small-time authority figures. Comics aimed at girls tended to be less rebellious in tone, of course; Girl, for example, which flourished in the 1950s and 1960s, “included the first fashion pages in a comic and the first ‘pin ups’: these ranged from the Duke of Edinburgh to pop singers such as Tommy Steele and Harry Belafonte.”

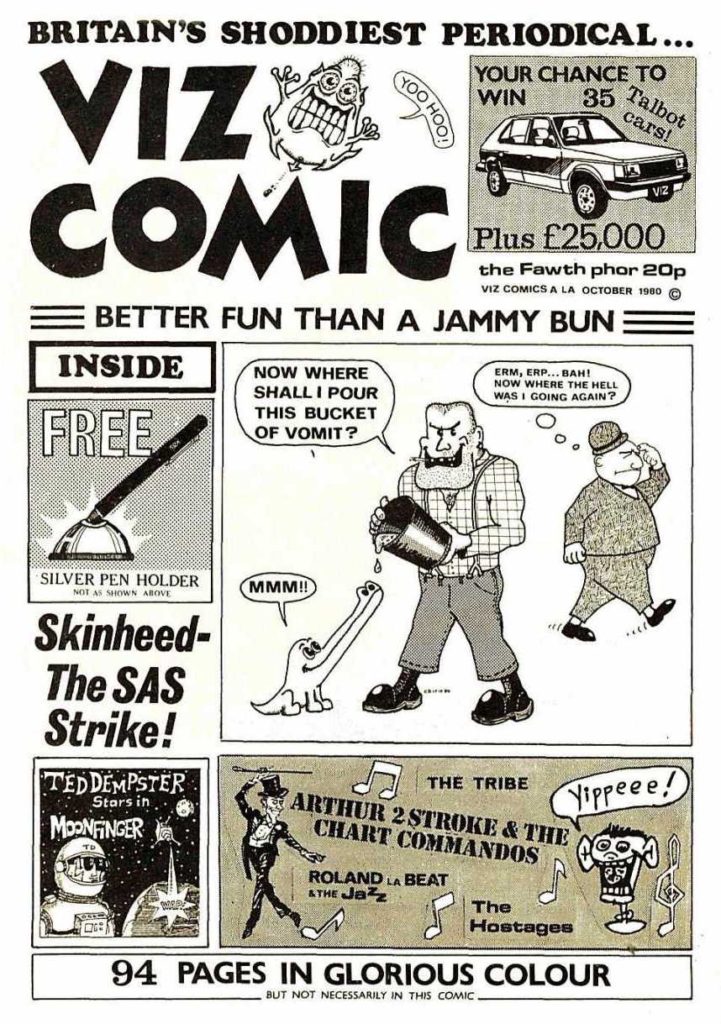

The best-selling comics magazine Viz, launched in 1979 (and reaching sales of 1.2 million in the 1990s), is very much in the juvenile-yet-class-conscious tradition of The Beano, even if its scatological joke-telling goes way beyond anything that would be allowed in titles published by either D.C. Thomson or the Amalgamated Press, the “big two” oligarchs of British cartooning. The names of Viz’s most popular characters – Johnny Fartpants, Buster Gonad, Billy Bottom, and Sid the Sexist – probably convey better than anything else the magazine’s distinctive brand of humor. In discussing Viz’s meteoric rise, Chapman usefully quotes from George Orwell’s famous essay on seaside postcards: “it will not do to condemn them on the ground that they are vulgar and ugly. That is exactly what they are meant to be. Their whole meaning and virtue is in their unredeemed lowness, not only in the sense of obscenity, but lowness of outlook in every direction whatever.”

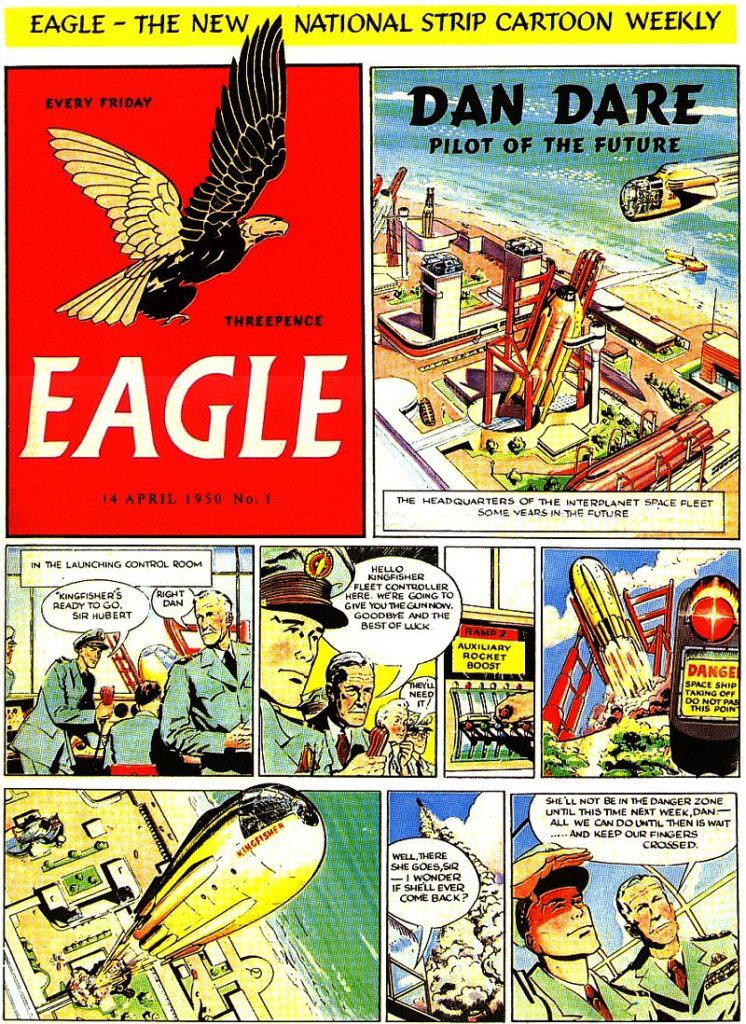

Not all juvenile comics magazines have been concerned with rebellion, clothes, or obscenity, however. Some of the country’s most popular comics magazines fixated on war, space exploration, or sport. “Arguably the most historically significant British comic,” Chapman writes, was Eagle, which appeared from 1950-1969. Conceived “by a Southport clergyman and former Royal Air Force chaplain as a wholesome British alternative” to American comics, Eagle was an “immediate success” that combined “picture strips with prose stories and topical features, particularly on science and technology.” Its most popular feature was the strip Dan Dare: Pilot of the Future, but it also included sport, crime, and western comic strips. The success of Dan Dare inspired several copycats, including Captain Valiant, Space Commander Kerry, and Rocket, which advertised itself as “the first space-age weekly.” Comics that depicted British soldiers in action included Ace Malloy, War Picture Library, Thriller Picture Library, and Bulldog Brittain Commando! As one journalist later remembered, “The men who saved our world didn’t have extraordinary powers, fancy gadgets or bizarre costumes. Our superheroes were our dads, uncles and grandfathers, and there is something rather touching in that.”

The story of comics is often framed in terms of the struggle between superhero comics and serious-minded graphic literature. As we have seen, neither of these two poles quite captures the British mainstream. English, Scottish, and Welsh artists and writers have cranked out superhero stories, of course, as well freestanding graphic novels. But many of the greatest British cartoonists – for example, Frank Hampson (Dan Dare), Steve Bell, Jim Holdaway, Leo Baxendale, and Hunt Emerson – rarely if ever produced work that comfortably slots into either category. James Chapman has penned the first truly scholarly survey of the origins and development of comics in Britain, and he focuses for the most part on titles and publishers, social trends and cultural shifts, rather than individual writers and artists. He’s produced a solidly researched piece of cultural history, but there’s a lot more to said about this fascinating topic.

By Kent Worcester, as originally published on The Comics Journal (“British Comics: A Cultural History“). Worcester’s books include A Comics Studies Reader (coedited with Jeet Heer) and The Superhero Reader (coedited with Charles Hatfield and Jeet Heer), both published by the University Press of Mississippi.

Header image: Eagle © Hulton Press