October 2017 sees the release of Blutch‘s Variations. Although the book is only being published in French at the moment, we couldn’t resist paying a tribute to this unique work. You will find here the translated preface of the book, written by Blutch, as well as a few translated pages placed next to the originals they’ve been inspired by. You can purchase the original French edition from our partner Dargaud.

Comic books baffle me. I have thirty years’ worth of published work under my belt and I still can’t make up my mind about them, to identify their overarching trends, to draw lasting conclusions, to settle on a credo, a style… and I am compelled to concede at the end of the day, that I have, in fact, understood nothing. We read the drawings and look at the writing. Since 1987, I have happily followed red herrings, collected false clues, rushed into dead ends, became mired in pastiches and satires, documentaries and autobiographies, sagas and essays, testimonies and fairy tales, and managed to accumulate countless unfinished projects. This endeavor—I dare not call it a profession—which has filled my life for many years, has a manifold appeal, not least of which is the ability to raise questions that remain unanswered. Every new book has me starting from scratch, staring at an obscure formula, which I endlessly attempt to decipher, despite the knowledge that any reassuring resolution is out of reach and that, once the task is achieved, solace will be fleeting and the mystery will remain.

Somehow, found myself drawing unconsciously, buoyed by the comfort inherent in the practice, away from domestic chores, social obligations and even road traffic. Armed with my colored felt pens, I methodically copied frames taken from Scrooge McDuck, Lucky Luke, Asterix, Achille Talon… it became an extension of the games I played as a child and the pleasure I found in reading. Sitting at the table, nose right up against the paper, depicting vignettes became a kind of compulsion, by which I mean I didn’t really know what I was doing. I was drawing without purpose, without a target, to put it more crudely. Led simply by instinct, I felt that every finished drawing, whether it was satisfactory or not, led to another one, and so on and so forth. In a way, this holds true forty years later. Drawing is a clear language, primitive, untranslatable and relentless. This language becomes more eloquent, even brilliant at times, when the action producing it is aimless; we draw without purpose or reason, for nothing, and this is where the game gets tough. How do you preserve this honesty in the professional and domesticated practice of creating comic books?

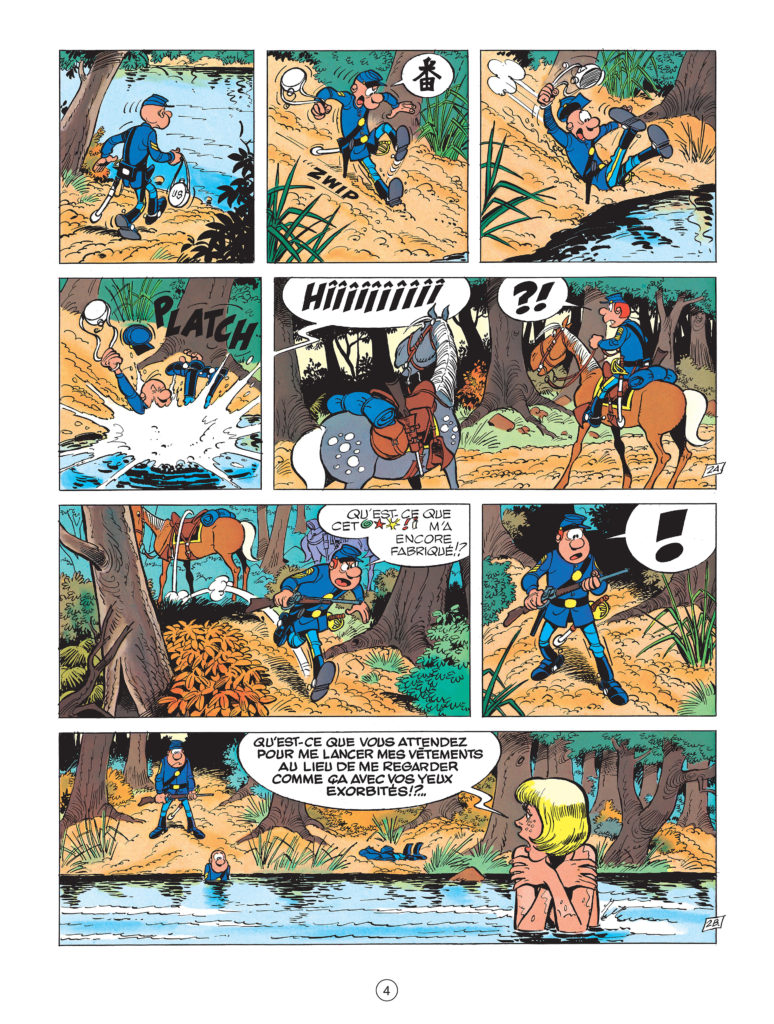

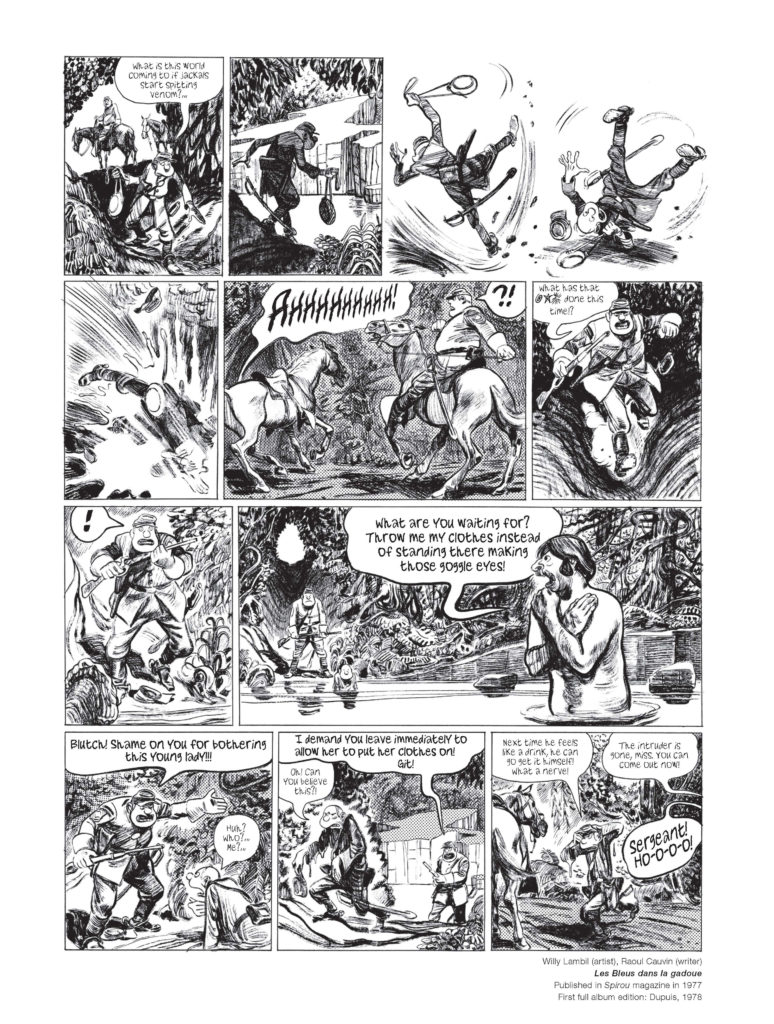

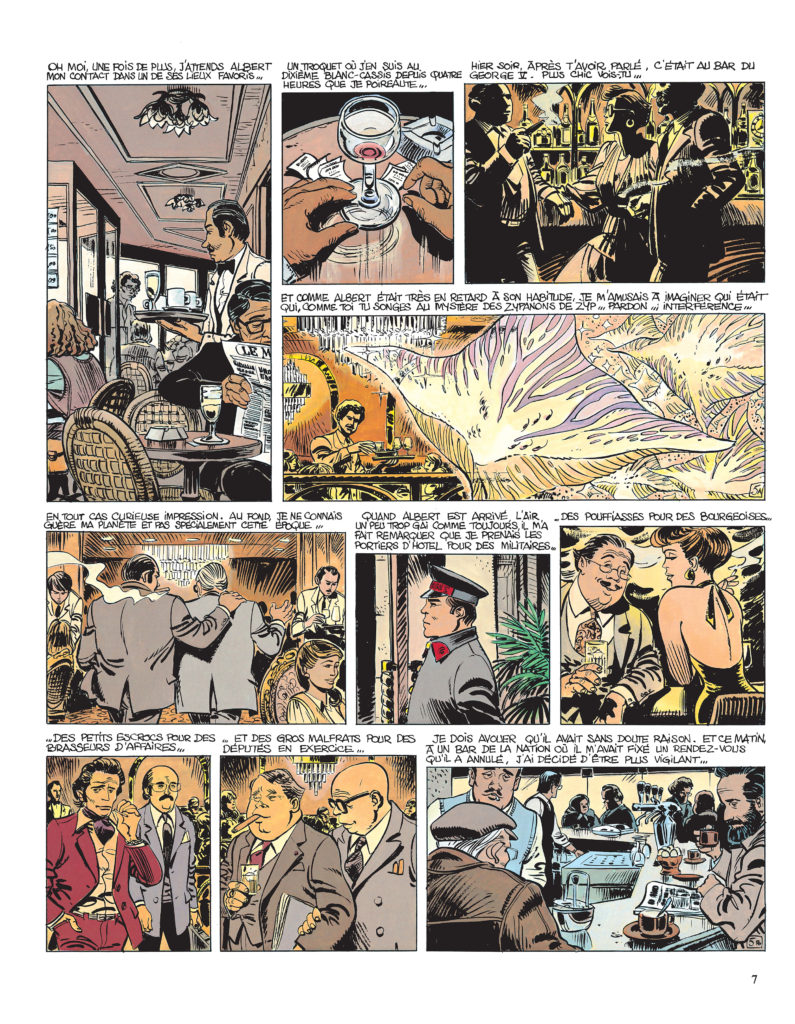

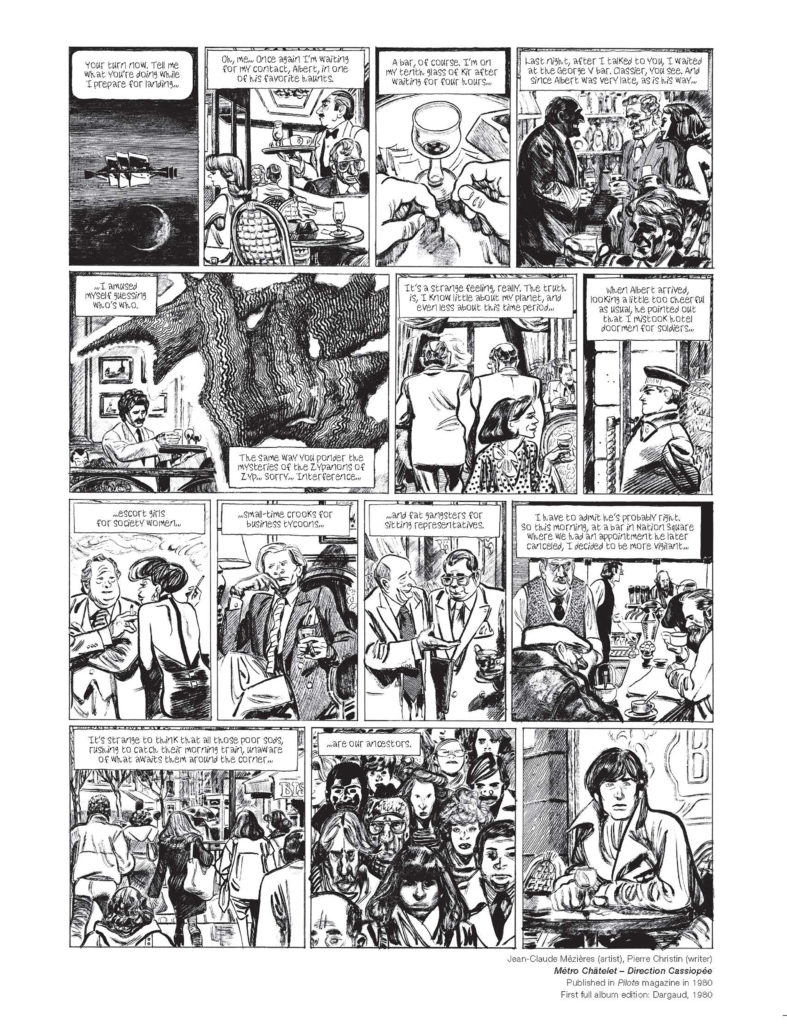

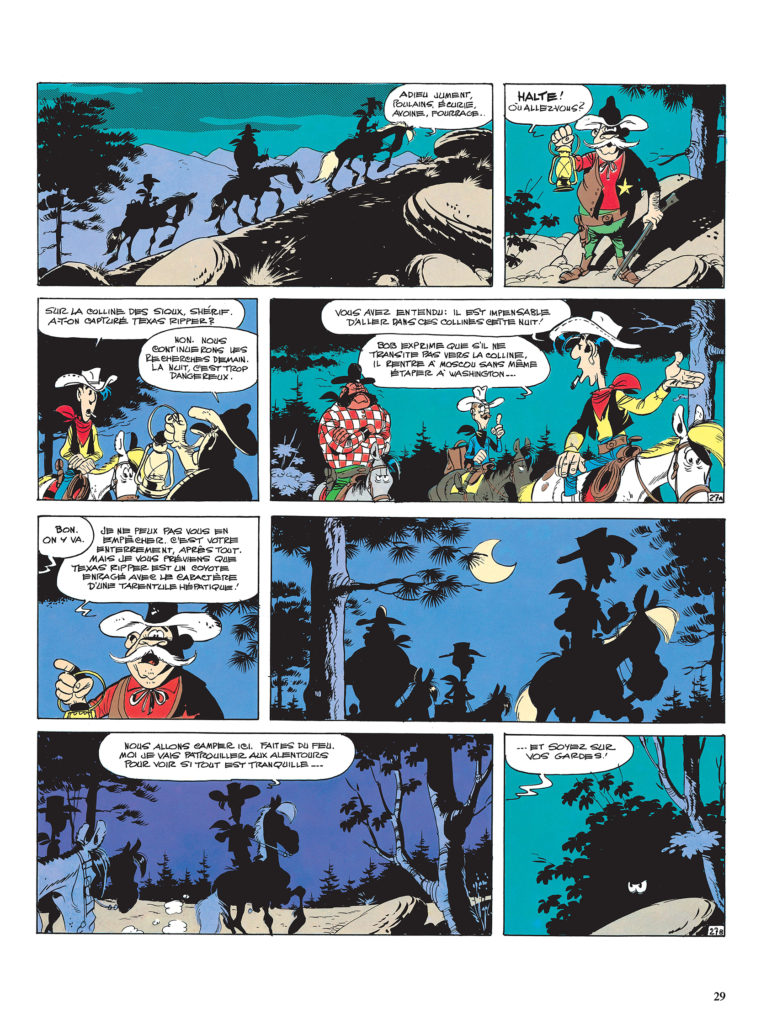

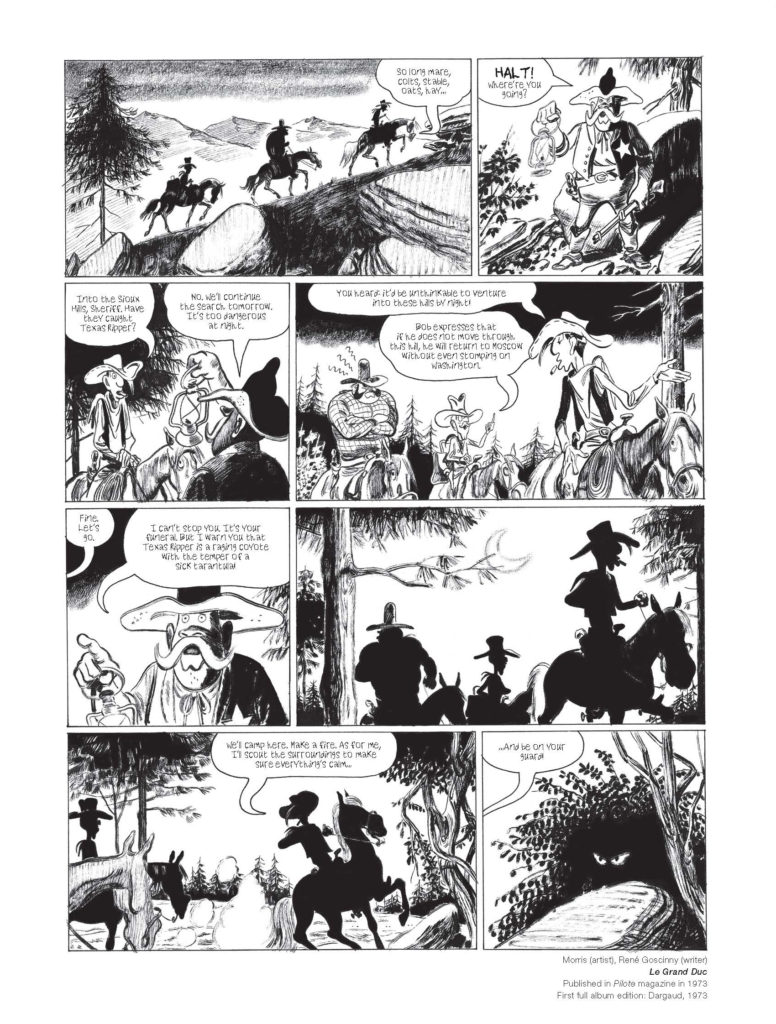

Since mid-2015, an unplanned project took me by surprise and has kept my attention: I have been painstakingly trying to reinterpret my favorite comic books. I picked thirty. You could say I’m covering them like a jazz artist covers a classic. My task consists of taking an excerpt from each selected album, laying it out on a single page and drawing it again. It is my way of returning to my origins, specifically my “European education”, by visiting each classic in turn (US and Japanese works form the subject of not-yet-written chapters, which I might get to at a later date). The youngest author in this collection of greats is Daniel Goossens, born in 1954; the oldest, René Pellos, was born in 1900. This set of disparate pages, taken together, forms what I call my cover album, Variations. By scrutinizing those who preceded us and extracting their essence, I’m not looking to return to past emotions, faded with time. Instead, I aim to discover new emotions by sitting in their place, tracing my steps over theirs so as to understand them; and understanding means creating anew. Copying has two opposing aspects: in one sense, it’s a humble way to go back to the academy, practicing the scales, but in another, it’s a proud challenge to my predecessors. This way I have to argue my case, to move past my limits. Such work is full of bravado. Variations is a patchwork of an album. The reader is met with a sequence of truncated stories, rife with allusions and enigmas, like thirty fragments chipped from a crumbling mural that I have collected and stuck together in a scrapbook. Most pages have neither beginning nor end, and the scenes they represent offer little satisfaction to the amateur accustomed to tidily-resolved intrigues. There used to be a show on French television called La Séquence du spectateur, which filled my Sundays as a child with joy. It simply consisted of three movie scenes shown back to back, in an era when cinema was barely accessible and rare enough to be a precious experience. Those intriguing movie scenes were powerful and evocative, enchanting even; they excited my imagination and curiosity. Some of the comic books covered in Variations are now long-forgotten; they are lost continents, like old movies, patiently waiting to be rediscovered.

I remember in 1988 we emerged deeply impressed from the “Last Picasso” exhibition at the Pompidou Center. Fifteen years had passed since his death, but the old man was still making waves. Amidst the unsettling frenzy of his work, I was uniformly impressed by his successive explorations of Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger (Women of Algiers), Veláquez’s Meninas, and Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the grass). At the time, his stubborn insistence of reproducing and dismantling these paintings, linking variations of the same subject, distilling them but failing to extract a satisfying answer, seemed to me the essence of artistic work. “Easy answers are never a given to those who seek” was asserted rather fittingly by François Porché in his biography on Paul Verlaine: “Even after observing these trends, very little comes to light. The needle of the compass might revolve around ever-diminishing circles, but the center remains unknown.” This tendency towards reinterpretation is what drew me towards Paul Cézanne’s chaotic version of Moderne Olympia, painted ten years after the original work by Manet, or Bacon’s incongruous Semeur, inspired by Van Gogh, and then towards Giraud’s spectacular pages published in Pilote, which reinterpreted Lucky Luke’s Pied-Tendre, as well as the many versions of My Favorite Things distorted by John Coltrane, or even Wayne Shorter’s Sanctuary electrified by Miles Davis, the latter being a few examples among many. Jazz offers an endless realm of possibility for this type of experimentation.

And, in fact, much in the same way one plays music, couldn’t we say that one can “play drawing”? Let me sum up the task I set for myself: to reconnect with the act of playing, the joy of playing and, as a consequence, the joy of drawing, which is both childish and obsessive. I realize again (it’s far from the first time) that I’m choosing the comic book that may be read, over the comic book that you look at. The scenes which are depicted are felt rather than understood. Storytelling yields to aesthetics, horizontal views give way to the vertical, and this reversal, as liberating as it might be (“at least” as Philip Roth says, “at first, when you don’t know where you’re going with it”) , fails to provide a clear direction. My thinking doesn’t go as far as that. On my better days, however, I feel like I’m lifting a veil and, without referring to the indescribable—or even worse the intangible—I maintain that the comic book can be a peculiar—and, why not, an original—form of poetry.

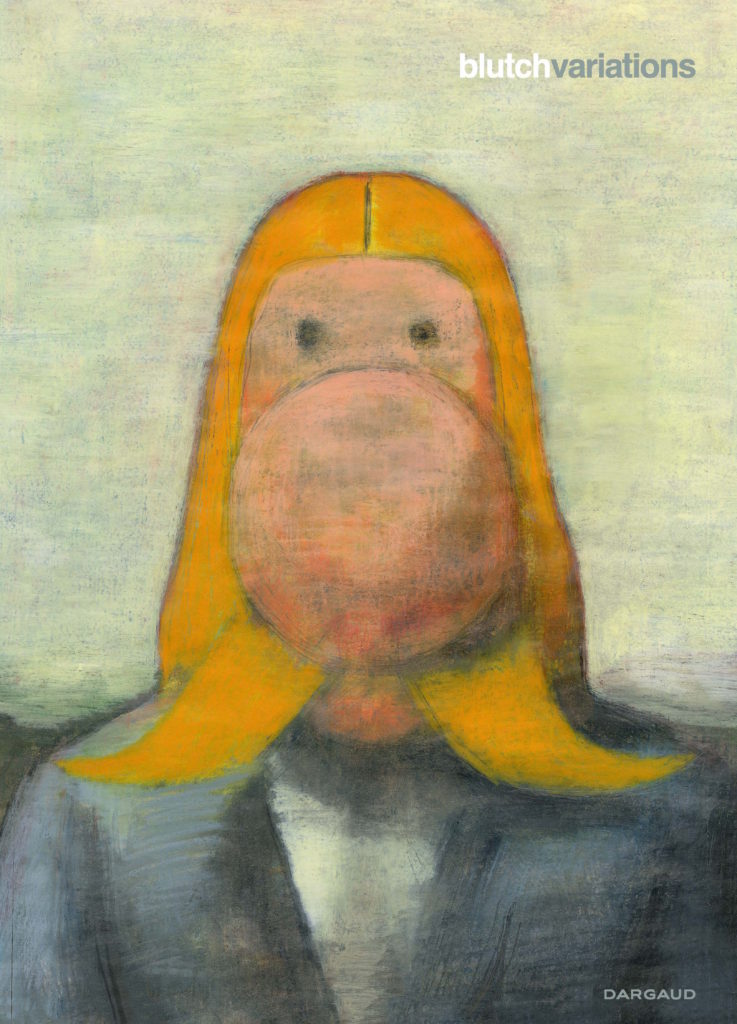

Cover image from “Variations” © Blutch / Dargaud 2017

Translated from the French by Storyline Creatives