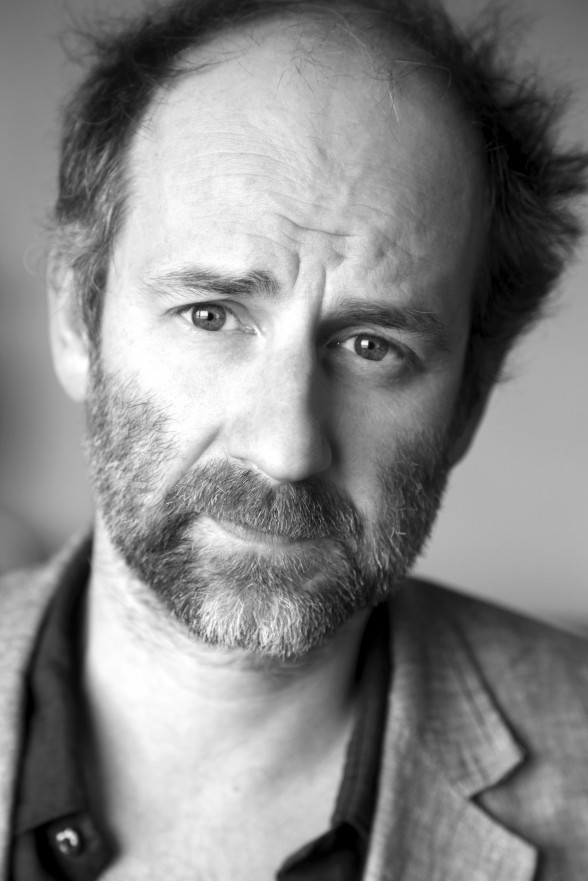

Christian Hincker, also known as Blutch (b. 1967), is despite himself a wielder of paradoxes. His pen name stems from a resemblance he bears with the antimilitarist corporal from Les tuniques bleues (Dupuis; in English The Bluecoats, Cinebook), a classic Belgian bande dessinée published in the comics weekly Spirou. Upon examination of the author’s career, punctuated by detours and experimenting art forms that are at times avant-gardist, the choice of an alias referring to what is generally considered a children’s classic might seem odd at the least—even if the last ten years have seen the rise of a form of post-modern creation that has cultivated a mischievous relationship with those post-war classics, a movement that Blutch himself has recently plunged into. Following a period of stark opposition between the old guard and the new, this form of post-modern comics has played a rather conciliatory role, which is why Blutch’s work in this direction over the past decade carries unique significance.

The author’s reversion to conventionalism dates back to 2009. At the time, Blutch had just stopped working on the third episode of the series Blotch, published by Fluide Glacial, despite having completed fifteen uproarious pages, and he had also shelved a project about his artistic influences, this time after ten pages. Nothing seemed to satisfy him. His sole desire was to return to a more classic form of comics—a form he had spent his whole career running away from, moving farther and farther away from conventionalism with each of his books. His previous works, published by Futuropolis, had in fact been quite extreme, leaving the reader to wonder if Blutch wouldn’t soon leave the realm of the Ninth Art altogether to explore other forms of illustration, perhaps more noble in some regard. But that would be to forget that comics had always been a major focus for the author, if not the major focus. This was the medium that had made him, and it seems clear that he will always come back to it, even if he may stray afield at times, trying his hand at experimental books or brilliant forays into other forms of illustration or even the cinema.

The beginning

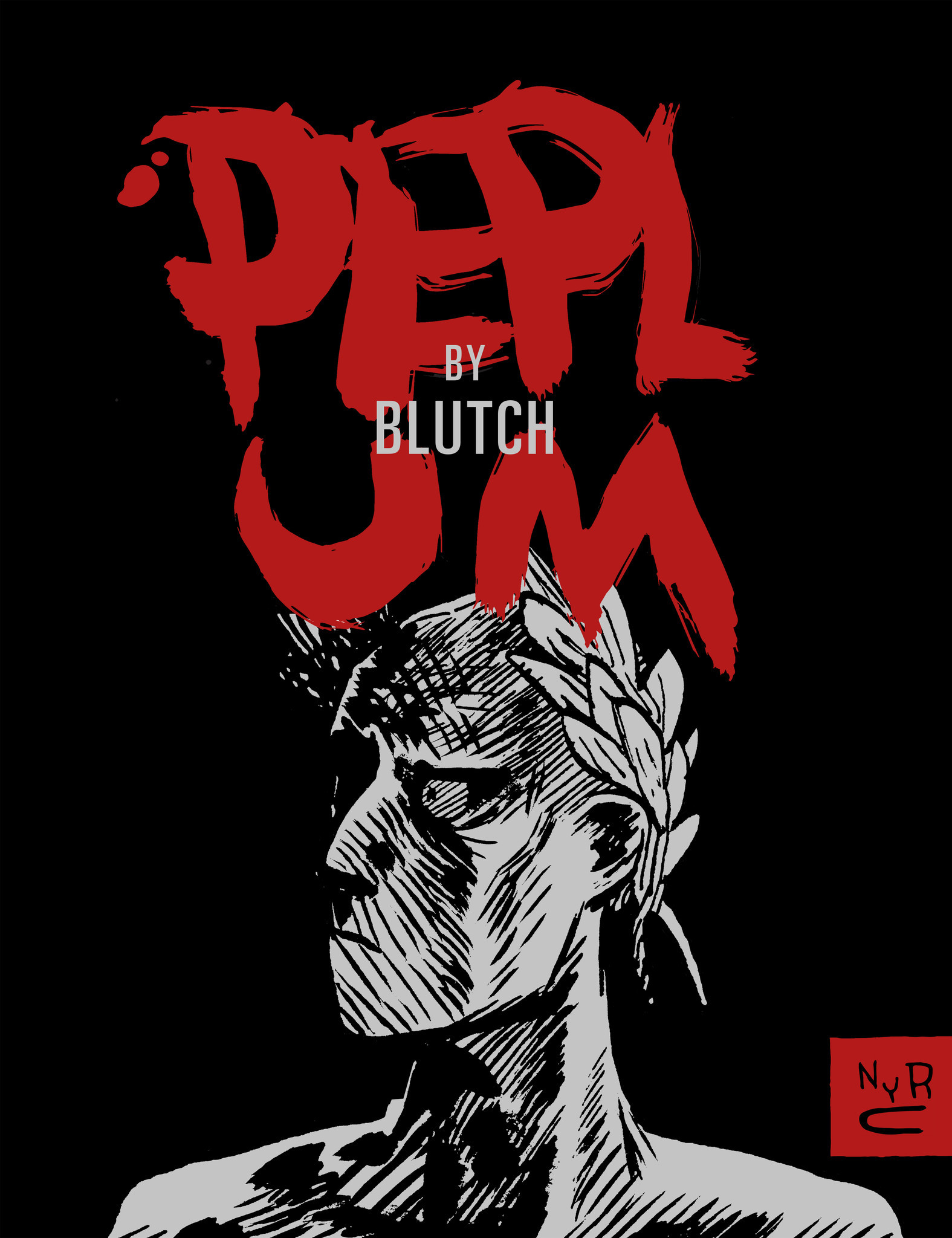

Blutch began his career at the end of the 1980s with Fluide Glacial, Gotlib‘s madcap comics monthly where his never-before-seen poetic approach designated him as an heir to the throne of the great comics author Jean-Claude Forest. For Blutch, this period was marked by Waldo’s Bar and Mademoiselle Sunnymoon, but the first real shock came with Peplum, equal parts adventure story and adventure in the making. Begun in the prestigious comics journal À suivre, the tale is a brilliant, liberal adaptation of Petronius’ Satyricon, cut short, bashed about, and finally interrupted, before being taken up by the scrupulous publishing house Cornelius, which turned it into a monster of aestheticism and decadence, as well as one of the greatest graphic novels of the last thirty years. But Peplum is also a reflection of the savage, untamed universe tirelessly explored by Blutch in his various graphic laboratories, an approach which may explain the limited public success of his works.

Jean-Louis Gauthey, Blutch’s editor at Cornelius, explained his modest sales as follows: “Blutch undoubtedly suffers from the fact that in each of his works he opens up a new world, only to then abandon it. He wants to mock neo-conventionalism and conservatism in art, so he does Blotch with Fluide Glacial. He wants to do a contemporary tale in a full-color hardcover volume, so he creates Vitesse moderne with Dupuis (Modern Speed, Europe Comics, 2017). Then he decides to focus on exploring new forms of drawing, along the lines of Saul Steinberg or Sempé, so he does Mitchum with us.”

His previous series of works, which began with C’était le bonheur, La Volupté and La Beauté at Futuropolis, also confirms the considerable influence Blutch wields over the comics world. This boldness is admired and often imitated by other artists, in vain, as noted by Jean-Christophe Menu, who was Blutch’s editor at the publishing house L’Association for Le petit Christian: “For many authors, myself included, Blutch is a model in terms of the purity of his approach and the perpetual renewal of his work. But, as a graphic virtuoso, there is also the superficial influence he holds, and his imitators of course retain nothing but that, reducing all of his instincts to mere technique. For example, there was a kind of ‘brush-felt pen’ technique typical of Blutch for a while—a way of giving volume to his drawings through satiny clusters of short strokes—that was copied enormously, a bit like the cross-hatched strokes of Mœbius thirty years ago.”

From sequential art to other artistic forms

With Futuropolis, likely tired of being imitated at every turn, Blutch moves in a radical new direction. He begins to warp existing comics codes to the breaking point, creating a new grammar for each new work, to the point that readers might ask themselves if these books still qualify as comics. And rightly so. As never before, Blutch tugs the Ninth Art toward “contemporary” drawing and other areas that interest him. He begins to experiment with press cartoons in 2005 with C’était le bonheur, finally reaching a kind of acme with La Beauté, his last book with Futuropolis. This strange collection of contemporary drawings, loaded with subconscious meaning, offers a silent and still universe with motifs suspended somewhere between Balthus and Bergman. Many critics are skeptical: is there a story to be found in these pages? Lacking any sequential illustrations, do these drawings nonetheless form some kind of narrative? Can a portrait be reconstructed from this material, perhaps that of the author? Once more, narration by illustration is at the heart of this ultimate experiment of the form. And once more, the experiment is carried out to the breaking point. Thus the cycle closes, followed by a long period full of doubt. At the end of these years of wandering, a new Blutch will finally emerge, one who has made a full about-face.

Return to conventionalism

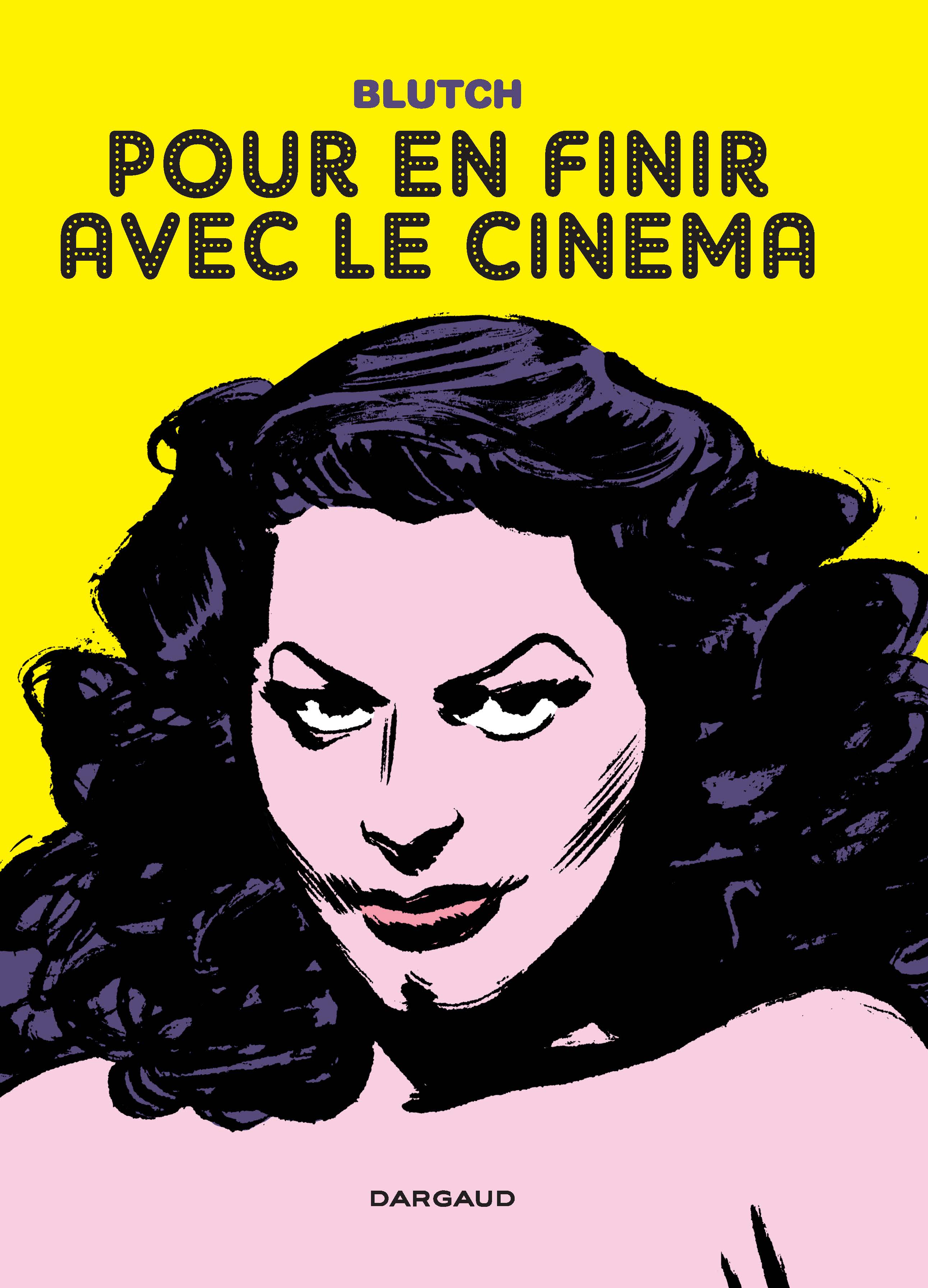

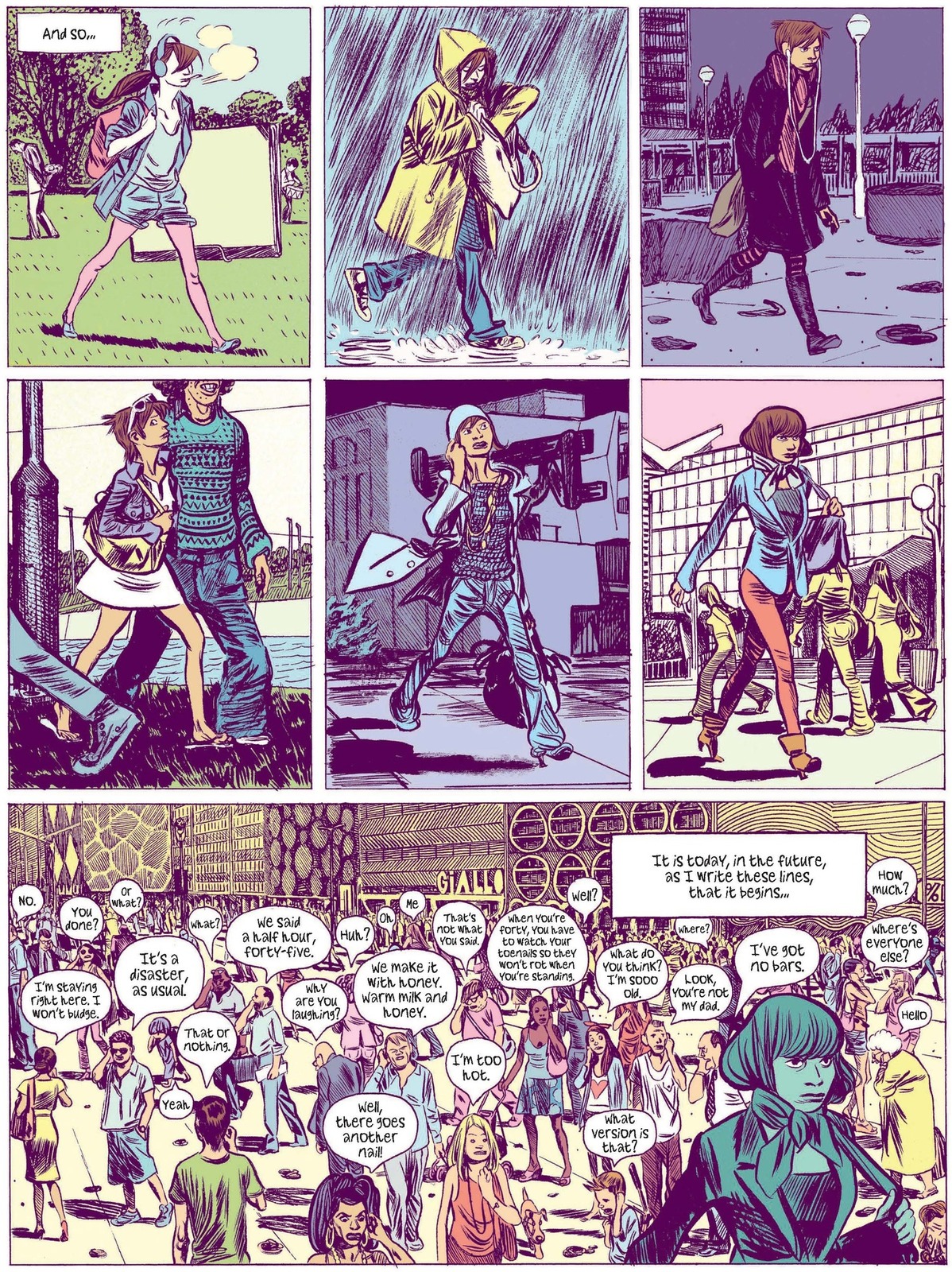

With his graphic novel Pour en finir avec le cinema (2011, Dargaud; So Long, Silver Screen, PictureBox 2013, Europe Comics 2017), Blutch returns to the basics of his chosen art form. His drawing style becomes highly technical, outlined by brush and in ink, neither too realistic nor too caricatural, and the reader once more finds narrative continuity and sequences of several pages. The frames are even traced by a ruler, for the first time in his career. Undoubtedly, this title opens a new cycle for the author, and it appears to bode well. The work comprises an autobiographical element as well, in the way that a film-lover reveals the most about himself when discussing his passion for the cinema. This kind of implicit self-portrait touches the listener more deeply, with an offhandedness draped in a silver screen and 24 images per second. The cinema feeds the creation of a kind of libido filled with beauties and beasts, with its anguish over the degeneration of the body, its vision of the masculine ideal, its sadness in the face of the decay of artistic value among aging artists, and its doubts regarding the utility of this whole masquerade. What is more, this imaginary world is enhanced through the practice of drawing. When Blutch reproduces a scene, the original image and the loving interpretation of its artist are superimposed. The drawing itself speaks more than the words; the line distills the nuances of the subject.

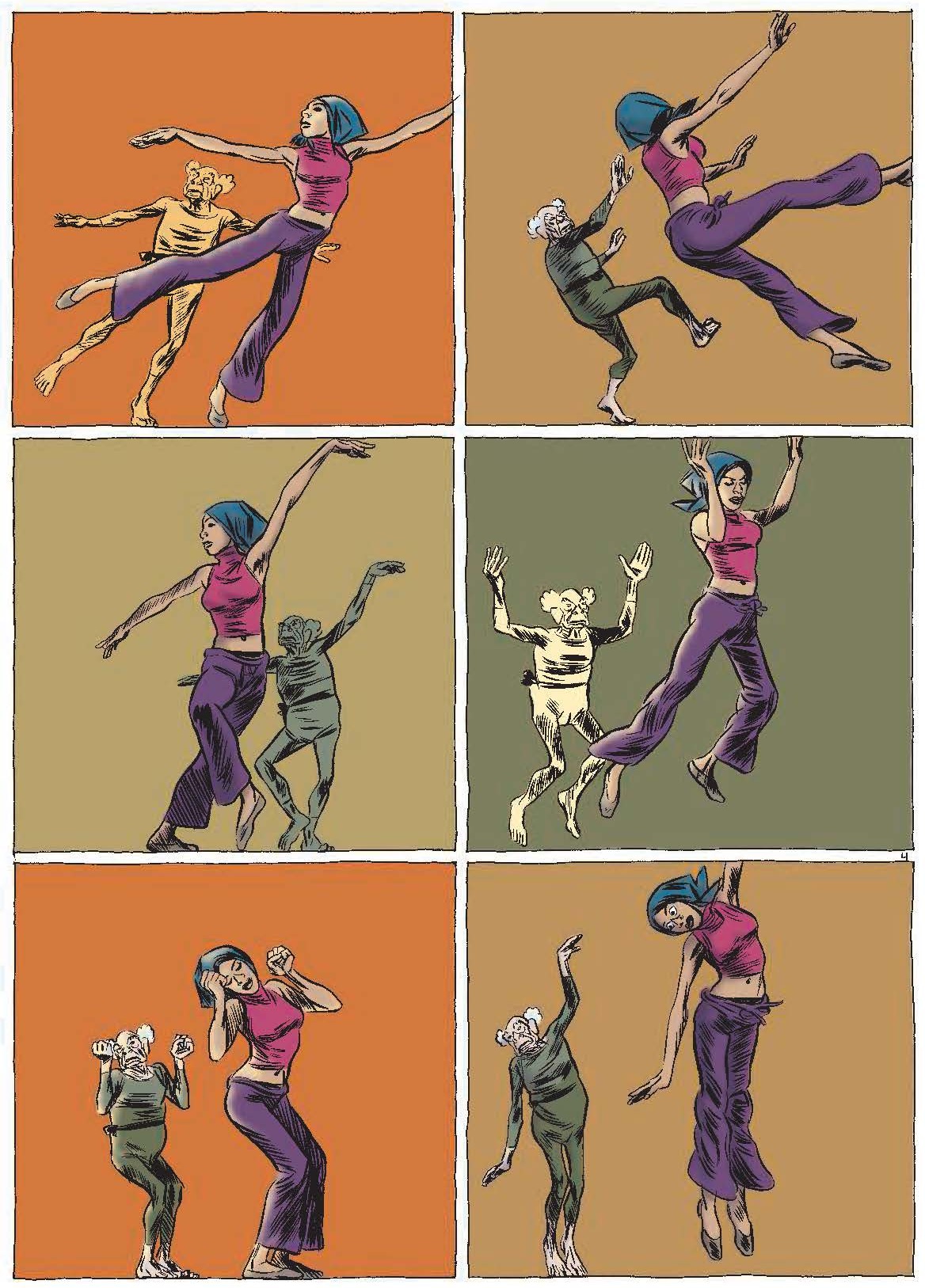

In 2014 comes Lune l’envers (Dargaud; Dark Side of the Moon, Europe Comics, 2017), 54 color pages with a sheen of old-fashioned science fiction behind which rumble the artist’s virtuosity but also his anxieties. By all evidence, Blutch opened with So Long, Silver Screen a creative cycle where his conformity of the form hides a darker kind of disguised autobiography. In Dark Side of the Moon, Blutch goes on a symbolic reconquest of his lost innocence, worn away by the years spent practicing his art, with a good dose of humor and even more humility. That is why his drawings, imbued with such incredible strength, dedicate themselves to masking his virtuosity behind various references. But the reader mustn’t be fooled: even bent under the weight of his guilt and legacy, Blutch remains by far the most inspired and demanding artist of his generation.

Today, Blutch is working on two new projects in parallel, each of them delving deeper than ever into the conventionalism of Franco-Belgian comics in the post-war period, in an effort to further warp it. The first project is a new episode of Tif et Tondu which is being written by Blutch’s brother, for whom it will be his first comic. The second project is a bit more particular, with Blutch taking up cult favorites from his childhood and reworking them in his own way, changing their framing, composition, and text. Once more, the artist’s creations will thus be driven by post-modernism, again in the form of a disguised autobiography.

From Forest to Mœbius, from Hergé to Franquin, from Resnais to Burt Lancaster, and even Sun-ra or Miles Davis, the creative figureheads we glimpse are more imposing than ever, but that is perhaps the price to pay for a brazen talent such as that gifted to Blutch by the muses.

By Stéphane Beaujean, Artistic Director of the Angoulême International Comics Festival

Cover image from So Long, Silver Screen © Blutch (Dargaud 2011, PictureBox 2013, Europe Comics 2017)