By Cynthia Rose

The Smurfs are global stars as big as Tintin. Like him, too, they’re a merchandising miracle. Yet even Hergé told their author he should forget about doing comics. So how did a dreamer with no obvious talents end up fathering world-famous icons? That’s the secret revealed in Peyo, a recent exhibition in Paris.

The Smurfs were invented by Pierre “Peyo” Culliford (1928-1992). Though he was born outside Brussels, both his father and his grandfather were English. Their family tree had one exotic sprig – an 18th-century pirate by the name of Robert Culliford. But Pierre’s own father, naturalized a Belgian, was thoroughly bourgeois. He installed his wife and three children in a spacious home, shared with not one but both sets of grandparents.

Pierre was the family’s youngest son, initially known as “Pierrot.” But an English cousin mispronounced this nickname into “Peyo.” Peyo was a sociable child who loved sports and storytelling. Every Sunday, after lunch, he would stage a play for his family. These productions always had historic themes, inspired by Hergé’s Tintin or the U.S. comics in Mickey and Robinson. Yet there was something sinister in the Culliford home. Peyo’s father was suffering from a mystery illness which, over several years, slowly paralysed him. One night when he was seven, Peyo was called to tell him goodbye. As the boy kissed his father’s face, he realized it was cold.

He looked for solace in music, drawing, and the Boy Scouts. But while the Scout choir was happy to make him a soloist, Peyo’s art teacher told him he had “no talent at all.” When he was twelve, the Nazis marched into Belgium. By his fifteenth birthday, the family was impoverished. Forced to quit school for work, Peyo became a movie projectionist. Culliford Senior had loved the cinema and he used to screen silent films at home. But Peyo, who worshipped Errol Flynn as Robin Hood, was stuck showing endless reels of German propaganda. One exception was a strange French movie, Marcel Carné’s Les Visiteurs du soir (The Devil’s Envoys). A medieval allegory of good and evil, Peyo watched it over and over. He never forgot it.

In search of better wages, he spent his spare time looking for jobs. One day, having just missed a posting seeking a dental assistant, Peyo decided he would answer every ad. The next one, from a company called the CBA, changed his life. The CBA was the Companie Belge d’Actualités, a business owned by the journalist Paul Nagant. It was started in Liège to make cinema newsreels. But, under the Occupation, “news” was a no-go area, so Nagant moved to Brussels and switched to animation. He hired a motley crew of students in their twenties, art school pals like Eddy Paape, Jacques Eggermont, Georges Salmon, and André Franquin. Another, Maurice de Bevere — better known as Morris — had studied art by correspondence and was dying to draw cowboy stories.

Peyo, only 17, was hired as a colorist. He was thrilled to start work on Le Cadeau à la fée, a tale about elves wearing flowers for hats. His lucky break, however, lasted less than a year. Suspected of collaboration, Nagant was arrested. Once he was detained, the CBA evaporated. Determined to become an artist, Peyo enrolled in the Academie des Beaux-Arts. But within months he had met Janine Devroye, who was going out with a friend in his choir. To win over “Nine,” Peyo needed a steady job and he found one with an advertising agency. Advertising could offer a steady wage and a future, yet Culliford still dreamed about a life in comics. So he also applied to the just-launched Tintin magazine. Although he was interviewed by no less than Hergé, his childhood idol firmly crushed his hopes.

The reason? Peyo’s early comics are shockingly stiff and awkward; even the best are uninspired and derivative. But, just as he pursued Nine Devroye (engaged in 1950, they married within a year), Peyo worked steadily to make comics his calling. Every month, despite the fact they were rarely acknowledged, he mailed off drawings and proposals. He had a couple of modest triumphs, appearing in Riquet and Le Petit Monde. He also got strips in a couple of newspapers. But every week, Peyo’s mother telephoned Nine to beg: Could she not talk Peyo out of this strange obsession?

Her worries were understandable, because World War II had decimated Belgian publishing. Children’s magazines lost access to their American strips – long the foundation of their popularity. The Occupation then caused a critical paper shortage. All the country’s publications shrank in size and many vanished. Yet by 1946, things were looking up. One reason why was Belgium’s local talent. Several youth publications had soldiered on despite the War, a feat made possible only by the artists on site. These creators, such as E.P. Jacobs and “Jijé” Gillain, were first used to ghost the missing strips. But, joined by new recruits like Willy Vandersteen and Sirius (Max Mayeu), they began to resurrect older, homegrown series. Then they began to create new ones. The popularity of such offerings grew and, when the imports returned, they were overshadowed.

Meanwhile, even before Belgium’s Liberation, work to restore the press was underway. Agents for what became the Office of Paper Allocation had discovered a pulp source in Scandinavia. Thus equipped, they revived publishing through subsidies. One aspect of their scheme proved important for comics: the fact that, from 1944 to 1946, paper was available only through a quota system. To receive “prime” quality paper, publishers were required to take the same amount in second-class goods. This inferior paper was used for kiddie supplements – around two dozen with names like Far West, Grand Coeur, Jeep, Story, and L’Explorateur.

Then there was the publication Heroïc-Albums (1945-1956). First monthly, then bi-monthly, and finally weekly, Heroïc was the brainchild of 17-year-old Fernand Chevenel. Rather than running week-to-week serials, it published entire stories. These tales, filled with action, echoed the crime fictions now popular with adults. Its content brought Heroïc a dubious reputation and this ended up limiting its circulation. But the journal was home to talents like Greg, Tibet, and Maurice Tillieux, and many of its staffers ended up at Tintin. The frustrated Peyo played no role in this renaissance. But it encouraged him to persevere alone. In 1946, in the daily La Dernière Heure, he published four frames entitled Johan, le Petit Page. Johan, a young and chivalrous teen from the Middle Ages, would endure where other experiments – pirate Capitaine Coky, Amerindian Tender-Foot, and detective Inspector Pik – did not.

Then, one morning, Peyo ran into André Franquin. Five years had passed since their time at the CBA and the two alumnae had plenty of news to share. Franquin had driven across America with Gillain and de Bevere (who was now “Morris” and living in Connecticut). Along with Eddy Paape, they were all working for Spirou magazine. Peyo confessed that he sent Spirou strips each week – but his work was always being rejected. Franquin volunteered to speak with publisher Charles Dupuis. Whatever he told the boss, Peyo was promptly hired. No one knows what Franquin saw in the struggling Peyo. But the pair became close friends, sharing everything from cocktails to babysitting. For years, the older artist would give Peyo astute advice. Decades later, Culliford told an interviewer: “Franquin set the bar for me and, over my whole career, I’ve worked hard to measure up.”

When Peyo joined Spirou in 1952, the magazine was almost as small as the CBA. Decisions were finalized by publisher Dupuis, with day-to-day direction from Jean Doisy and the versatile, generous Jijé. The other full-time staffers were Willy Maltaite (Will) and Franquin. Contributors like Paape, Jean-Michel Charlier, and Victor Hubinon were actually employed by World Press, the syndicator who doubled as Spirou‘s PR agency. Morris sent in his strip, Lucky Luke, from America. During the early 1950s, work at such publications was lowly. Comics were lumped together with all the illustrés for children, throwaway diversions for which the wages were derisory. In a conservative and materialistic Belgium, this only added to their staffers’ isolation.

Eventually workers at World Press tried to unionize (as a result, they were fired on the spot). But early on, no one had time to think about conditions. Instead, propelled by shared ideas and always-urgent deadlines, they turned Spirou into a little world of their own. It was this universe which made Peyo’s art possible and his career was tied to its human circuitry. Between 1952 and 1954, Peyo worked out the story of Johan. Using the sword-and-sorcery tropes he had always loved, he created a universe of loyal servants and royal bosses. Johan’s blond hair turned black and, in addition to minstrels and magicians, he gained a sidekick. This was a gluttonous, maladroit dwarf by the name of “Pirlouit” (for Anglophones, “Peewit”). Pirlouit would remain Peyo’s all-time favorite character.

The comics of Peyo’s youth contained few swashbucklers but medieval storylines were not completely absent. Culliford loved both Hergé’s pirate tales and Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant. But he also grew up with 1940’s Roberjac, Mousquetaire du Roy (Roberjac, The King’s Musketeer) and Spirou‘s 1941 Le Navire Fantôme (The Phantom Vessel). The latter, inspired by the legend of the Flying Dutchman, featured wild, baroque art by Fernand Vanhamme. Peyo also read the Arthurian tale Morgana (1944–1946) in Bravo!

The late ’40s brought a few more such fantasies: Wrill magazine’s Les Tribulations de Jehan Niguedouille (The Trials of Jean the Simple) as well as works by Flemish artists Bob de Moor (Le Mystère du vieux chateau-fort, 1947) and Willy Vandersteen (the series Lancelot). But, thanks to its storytelling, Johan was different. Peyo’s years and years of solitary revision helped the artist get a grip on narrative clarity. “That’s the skill of Peyo’s drawing,” Franquin always said. “Put one of his boards on the wall and step back five meters. You can still see exactly what’s going on.” Life at Spirou was busy, pressurized – and social. Its artists met less in the office than in bars, eateries, and each other’s homes. The Culliford home became one of its centers. “The first time I was ever invited over to Peyo’s,” said artist Jean Roba, creator of Boule & Bill (Billy & Buddy), “I told myself, ‘You’ve made it, finally you’re part of the club.'”

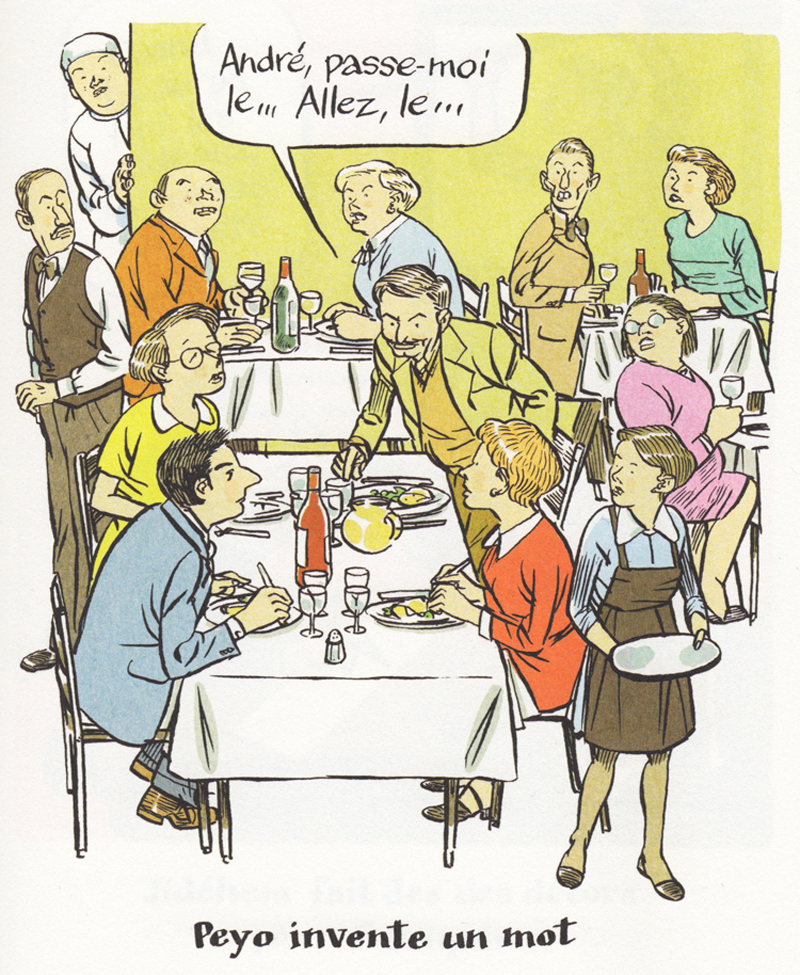

Unlike all his friends, Peyo never sketched in public. While the other artists would doodle on coasters or napkins, Culliford made notes. “He was always jotting down an idea or a phrase,” said Nine. “He might even get out of bed at night to write something down.” Carefully, Peyo filed all his notes away. Once, on a summer holiday, the Cullifords and Franquins were dining out together. Peyo wanted to salt his food but, halfway through asking, the relevant noun eluded him. “André,” he gestured, “Pass me the… pass me the… the schtroumpf!” Franquin passed the salt shaker, saying “Take it easy, here’s your schtroumpf!” and Peyo fired back, “Okay, when I’m through with it, I’ll schtroumpf it back.” Delighted with their game, the pair spoke schtroumpf all night. At evening’s end, Culliford jotted down the joke, thereby sowing the seeds for his most landmark series.

There are countless anecdotes like this from Spirou‘s heyday. All reflect a hothouse of percolating creativity, one in which skills and jokes were swapped without a thought. It was a heady and fertile world in which Peyo flourished and his best work radiates its zest.

The critic Serge Lemoine describes Peyo’s art this way: “Peyo favored the actual drawing — calligraphic strokes with no shadows or modeling. It’s a simplified line whose round rhythm connects all the forms. His shapes have presence but every character and all the decors are stylized. Any superfluous detail has been eliminated, so that every frame, every board, is instantly readable.”

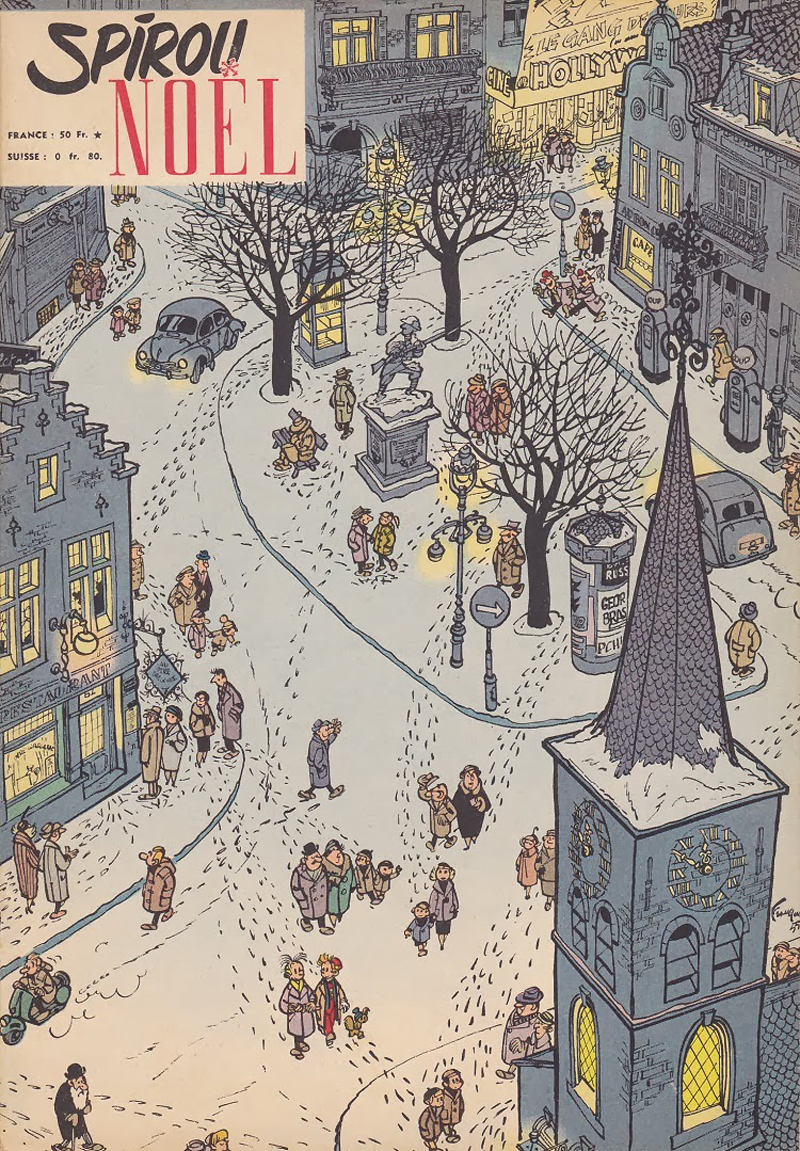

In 1954, Spirou jumped from 24 pages to 32. It also moved offices, into downtown Brussels. Charles Dupuis installed World Press on a floor of the premises – and he put Yvan Delporte in charge of Spirou. A bearded provocateur who viewed himself as an “anarchist,” Delporte had worked for Dupuis in several capacities. Fluent in Dutch and English, he was exactly Peyo’s age. Just like Peyo, too, Delporte had lost his father at the age of seven.

The lanky beatnik became an excellent editor. An expert in dealing with talents and egos, he was brimming with offbeat ideas. Delporte had an issue printed using perfumed ink, hired a marksman to shoot holes in a cover with cowboy Lucky Luke, and housed a real lion – “Pinky” – in his office. Abetted by his long-time pal Maurice Rosy, the editor surprised his staff as much as Spirou‘s audience. By the mid-’50s, when Morris returned from America, he found Spirou “a totally different publication, full of fresh ideas and new stars like Peyo.”

Then, in 1958, Culliford made history. As part of Johan’s ninth adventure, La Flute à six trous (The Flute with Six Holes), Peyo had Peewit discover a magic flute made by sprites. These little beings mixed the CBA’s elves with his accidental word from the previous summer. They became les Schtroumpfs, those characters that Anglophones would soon meet as Smurfs. It was Nine, who worked as her husband’s colorist, who made them blue. “That was a process of elimination,” she said. “Green would have mixed them up with the foliage; yellow would make them look ill. If they were pink, they would seem embarrassed, and if they were red, readers would think they were angry.”

No one objected to Peyo’s blue beings. But their “language” caused some problems. When Spirou‘s young readers tried speaking “Schtroumpf” at home, irritated parents soon made their feelings known. This was followed by teachers who felt that all children should be reading “proper French.” Peyo was called on the carpet by Dupuis. But the artist was used to being in such hot water – his first-ever Spirou strip had featured medieval torture. Later, in a magazine where no one ever died, Peyo deliberately drowned one of Johan‘s villains. This time, however, he had no worries. After all, the blue elves were extras in a single story. In a few months’ time, no one would remember them.

Continue to Part 2

First published on The Comics Journal. Cynthia Rose is a British writer, author, and broadcaster based in Paris. Her writings can be found on www.muchacreative.paris.

© Cynthia Rose, all rights reserved. Header image: Les Schtroumpfs © Culliford, Jost & Garray / Le Lombard