After decades of Spiderman, Batman and other Marvelesque heroes dominating the big screen, it’s no surprise that both French and international producers are starting to delve into the substantial archives of France and Belgium’s prolific comic book and graphic novel industry. Here we take a look at some of the blockbusters inspired by the European scene!

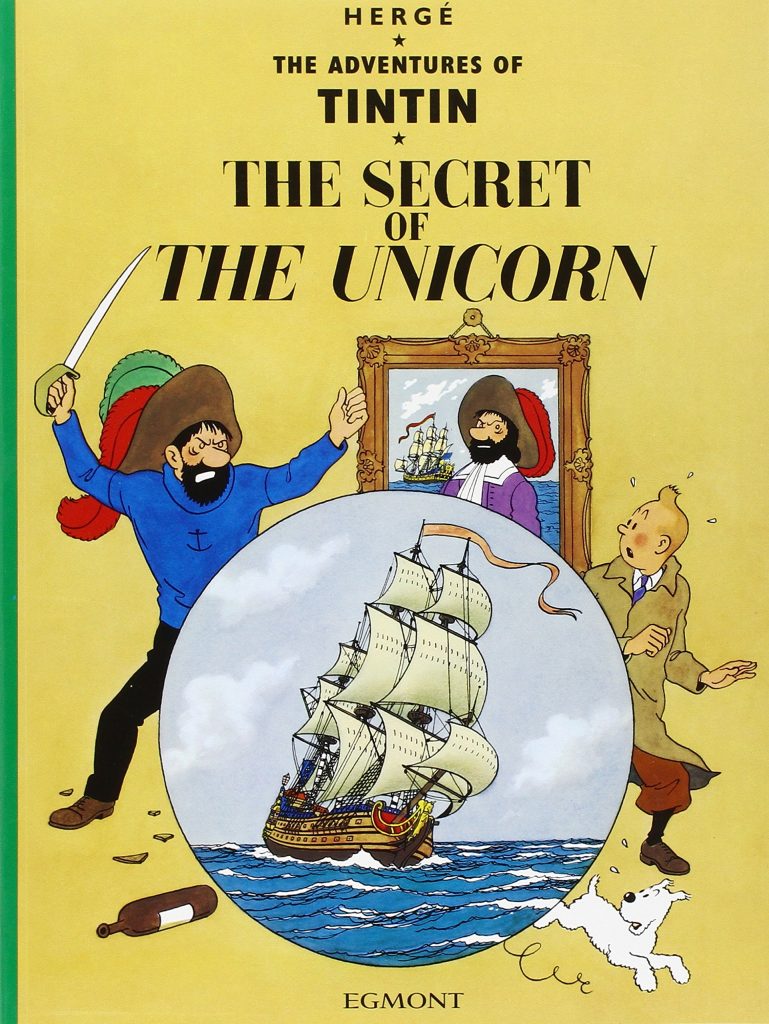

TINTIN

Author: Hergé

Publisher: Casterman. English language publishers: Methuen, Egmont

Movie directors: Claude Misonne, Jean-Jacques Vierne, Philippe Condroyer, Eddie Lateste, Raymond Leblanc, Steven Spielberg

The one and only Tintin, with his world-famous quiff, had the starring role in the world-renowned comic book series created by Belgian cartoonist Georges Rémi, otherwise known as Hergé (the French phonetic pronunciation of his initials, backwards). Hergé’s boy reporter first cropped up in 1928, in the youth supplement of the Catholic Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle. The series then graduated to one of Belgium’s leading newspapers, Le Soir, before Hergé went the whole hog and created his very own publication, the famous Tintin magazine. Full graphic novels were later produced, which have since been adapted to TV, radio, theater and film.

Tintin is an everyman of neutral attitudes and Boy Scout principles, tending to act as a foil for the more developed secondary characters surrounding him, such as his rough, alcoholic best friend, Captain Haddock. He’s apparently a reporter, although he is rarely seen actually turning in any work. What’s more, he was supposedly only about 13 or 14 at the start of the series… meaning that all those planes and helicopters he piloted, the race cars, motorcycles and tanks he drove, not to mention his handy pistol, were flat out illegal!

The series marked the beginning of the legendary ligne claire (clear line). If you look closely, you’ll notice that Tintin barely has a face, but just a few simple lines, easy to adapt from one frame to another. Hergé’s signature style influenced countless Franco-Belgian comics artists in the years since. Even Andy Warhol cited the Belgian artist as a great inspiration for him!

Despite the series’ success, there was some controversy regarding Tintin’s earlier adventures, which were accused of racial stereotyping, animal cruelty, colonialism, violence, and even fascism. Hergé claimed that his background made it impossible to avoid prejudice, stating in an interview with Numa Sadoul, “I was fed the prejudices of the bourgeois society that surrounded me.” Tintin himself maintains an impeccable sense of morality throughout, and is an unbigoted friend to all creeds and color. In fact, the Hergé foundation and Tintin series were even presented the Light of Truth Award by the Dalai Lama in 2006, for Tintin in Tibet!

Hergé managed to continue publishing the Tintin series in occupied Belgium all through WWII. Le Vingtième Siècle (Hergé’s original newspaper) was closed down under Nazi occupation for political reasons, leaving Hergé out of a job. That was when he moved to Le Soir, one of the few newspapers that continued production under German censorship. The restrictive climate of Nazi Belgium put an end to the political slant of Hergé’s tales, and Tintin became an explorer, rather than a reporter.

This period gave rise to some speculation about Hergé being a collaborator and Nazi sympathizer. He was eventually cleared, but, following the allegations about his war record, Hergé considered giving up on Tintin and moving to South America. That was when he got a leg up from Belgian publisher Raymond Leblanc (founder of Le Lombard) and established Tintin magazine as a competitor for the likes of Spirou.

While Hergé stayed put, Tintin traveled more than most people do in a lifetime, to both real and fictional lands, ranging from “Nuevo Rico” to the Soviet Union… and he even went to the moon five years before Sputnik, and 17 years before real-life man got there. Hergé released a sketch to celebrate the real landing:

Five movies were produced before Hergé’s death in 1983, but he wasn’t a great fan. He is said to have believed that Spielberg was the only person who could do justice to his oeuvre. Unfortunately, Hergé died the very week the two cultural giants had agreed to meet. His wife later granted Spielberg the rights, but it was nearly three decades before he at last managed to get the boy reporter onto the big screen with The Adventures of Tintin, starring Jamie Bell, Andy Serkis, Daniel Craig, Nick Frost and Simon Pegg. The world premiere was attended by the Belgian royal family, and was met with resounding critical acclaim. It was the first non-Pixar animated movie to win the Golden Globe for best animated movie, as well as several other awards, and a ton of nominations.

Fun fact: There’s even an academic discipline known as “Tintinology”!

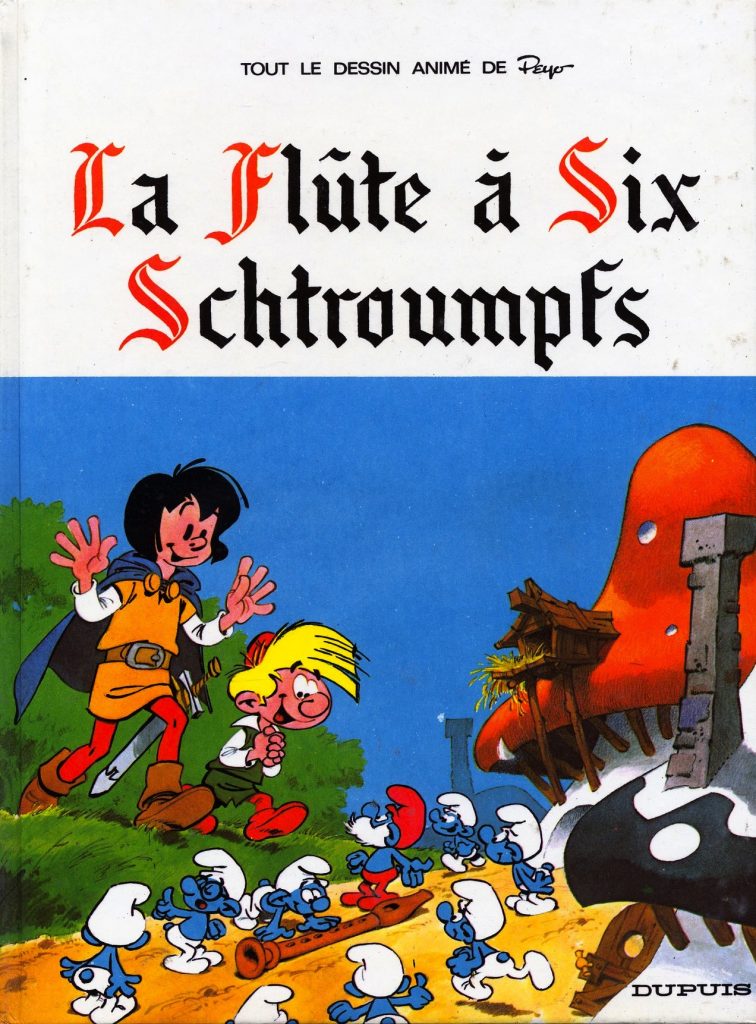

SMURFS

Author: Peyo

Publisher: Dupuis. English language publisher: Papercutz

Movie directors: Raja Gosnell, Kelly Asbury

Love ’em or hate ’em, there’s no denying that the Smurfs are one of the most impressive merchandising phenomena of our time. They first appeared in the world as supporting characters in Belgian author Peyo’s previous series, Johan and Pirlouit. Dupuis, Peyo’s publisher, was not exactly keen on the little blue imps, but the author promised that they would only feature in a few strips. Only a year later, in 1958, they had their very own series in Spirou magazine. A few decades down the line, the tiny creatures (“three apples high,” to be precise) have become an institution… and one of Belgium’s biggest franchises!

The series is about a community of tiny blue creatures living in a village of mushroom houses in the middle of a forest, and their arch-nemesis, the evil wizard Gargamel, who believes the smurfs are an essential ingredient for creating the philosopher’s stone. The smurfs were originally all male, until Smurfette was created by Gargamel in the hopes that she would lead them to their ruin with her feminine wiles. Of course, Papa Smurf saved the day when he “converted her,” which mostly involved turning her hair from black to blond. She is now one of three female smurfs (out of 101), and has remained the love interest of practically all her male counterparts!

Like most Franco-Belgian genius, the original French name (“schtroumpf”) was invented at the dinner table. Comic book legends Peyo and André Franquin were settling down to a nice beef bourguignon, when Peyo asked Franquin if he could pass the… damn, what’s the word… you know, the… schtroumpf…! They then spent the rest of the dinner speaking in Smurf language, which basically involves replacing random nouns and verbs with the appropriate declension of the word “smurf,” or “schtroumpf.”

Starting in 1997, American movie producer Jordan Kerner tried to obtain the rights from the series’ Belgian licensing agent. He had to wait five years before the Peyo estate finally gave him the green light, having read a draft of Kerner’s cinema adaptation of Charlotte’s Web. Since then, there have been three movies, and three brand new smurfs created for them, including a narrator. The first two movies were directed by Raja Gosnell, and were a mix of 3D animation and live-action, starring none other than Katy Perry as Smurfette.

The 2011 movie had its worldwide premiere in a little Spanish town called Júzcar. The whole town was painted blue for the occasion, churches and historical buildings included. Six months and a whole lot of tourists later, the residents voted to keep the iconic color, making it the only official smurf village in the whole world!

Fun fact: It was actually Peyo’s wife Nine’s idea to color the smurfs blue.

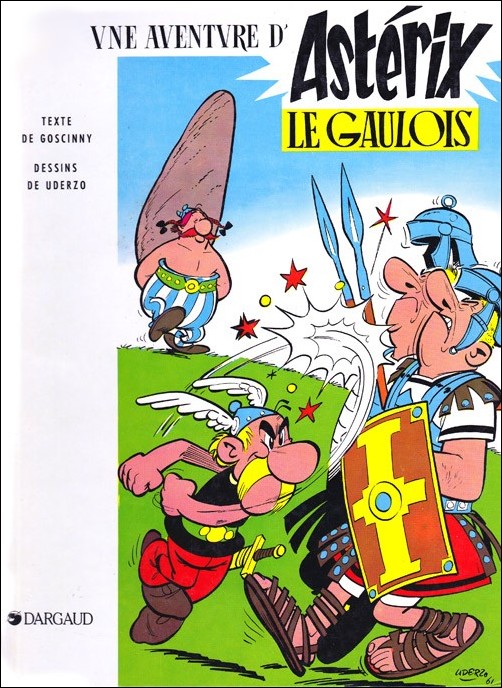

ASTERIX

Authors: Albert Uderzo & René Goscinny

Publisher: Originally Dargaud, now Albert-René (Hachette Group). English language publishers: Brockhampton Press, Orion

Movie Directors: Alain Chabat, Claude Zidi, Laurent Tirard, Thomas Langmann, Frédéric Forestier, Stefan Fjeldmark, Jesper Moller

Asterix is a cornerstone of French cultural heritage. It’s a series about a Gallic village tirelessly resisting Roman occupation, sometime around 50 BC. Their secret weapon is a magic potion brewed by the druid Getafix (yep, it’s intentional), which endows the recipient with temporary superhuman strength.

Since its debut way back in 1959, the Asterix comic book series has enjoyed the greatest commercial success French publishing has ever seen, with about 370 million copies sold, making Uderzo and Goscinny France’s bestselling authors. The comic book series has been adapted into more than a dozen animated and live-action movies, plus numerous board games, merchandise and even a theme park.

The live-action movies star the notorious Gerard Depardieu, a French actor famous for peeing in plane aisles, drunk-driving his scooter around Paris, a tax evasion scandal, and drinking excessive quantities of his beloved vin rouge.

The book series wasn’t translated for a long time because much of the humor was specific to France, the French language, and the French people. However, it has now been translated into 114 different languages and dialects, ranging from Vietnamese, to Gaelic, to Rumantsch Grischun (don’t worry, we hadn’t heard of that one either).

The English language translation by Derek Hockridge and Anthea Bell was met with particular enthusiasm, due to their remarkable fidelity to the humor and spirit of the original, despite direct translation sometimes being impossible. All names except Asterix and Obelix were altered to accommodate the clever wordplay of the original in the English translation. Some of our personal favorites are “Gluteus Maximus,” an athletic Roman soldier, “Valuaddedtax,” a Saxon druid, and of course “Dogmatix,” the hopelessly stubborn dog.

These fantastic translations opened the doors to the rest of the world, and now the series’ characters pop up everywhere, including South Park, The Simpsons… and even Nutella jars! Plus, James Bond, Laurel and Hardy and Don Quixote have all made guest appearances in the comic books. And it doesn’t stop at the world: the first French satellite was named Asterix-1, and there are a couple of asteroids out there that also bear the names of the famous Gauls.

This coming October will bring the release of the 37th adventure of Uderzo and Goscinny’s goofy Gauls, with authors Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad at the helm.

Fun Fact: Uderzo had two extra fingers when he was born, and was color blind. Maybe that explains why the characters’ hair keeps changing…

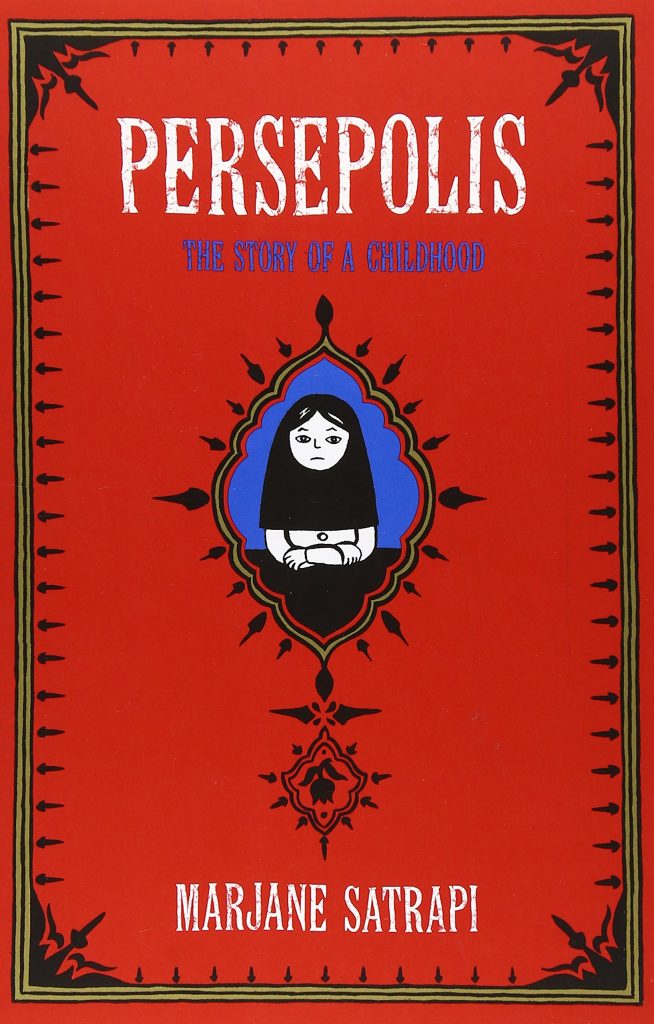

PERSEPOLIS

Author: Marjane Satrapi

Publisher: L’Association. English language publisher: Pantheon

Movie directors: Marjane Satrapi & Vincent Paronnaud

When Marjane Satrapi was 10 years old, she endured bombings and food shortages, her family members were imprisoned for their political leanings, and all schoolgirls were made to wear the veil. As an adult, she wrote a book attacking the tyrannical regime governing her homeland and her life.

Persepolis was undoubtedly the most successful (and controversial) Franco-Belgian graphic novel of the noughties, transforming Satrapi into one of the world’s most widely recognized French authors. In 2007, the animated movie adaptation, directed by Vincent Paronnaud and Satrapi herself, won the jury’s prize at the Cannes Film Festival, followed by several others.

This black and white autobiography is a testimony of the cataclysmic events of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, superimposed on the daily life of a liberal family in Tehran. The young Marjane discovers the joys of punk and ABBA, but also the horrors of war, fear, the tragic fate of women under the mullah regime, exile to Europe and isolation at the most crucial moment of her adolescence. It is a tumultuous coming-of-age tale of love, loss, solitude, liberation and marginalization.

The movie producers initially recommended a live-action feature, and were reticent about Satrapi’s choice of an animated movie. But Satrapi stuck to her guns, because, in her eyes, as stated in an interview around the time of the film’s release, “With live-action, it would have turned into a story of people living in a distant land who don’t look like us… At best, it would have been an exotic story, and at worst, a ‘third-world story.’” On Satrapi’s insistence, the film respects the stark black and white color palette and simplistic 2D style of her graphic novel. They used simple, traditional animation techniques, so that the film would never end up looking dated.

Despite critical and public acclaim internationally for both the book and movie, not everyone was happy! When the film won its award at the 2007 Cannes Festival, the French Embassy in Tehran received a rather disgruntled letter from one of Iranian President Ahmadinejad’s advisors. Still, the country’s cultural authorities did eventually allow limited screenings of the movie in Tehran, with a few sex scenes censored. Persepolis was also initially banned in Lebanon, because governmental authorities considered it offensive to Islam. However, they ended up backing down following the subsequent outcry from intellectual and political circles. And the tumult doesn’t end there – even in the US Persepolis raised a few eyebrows: it was listed as the second most challenged book of 2014 by the American Library Association, due to its “politically, racially, socially offensive” nature and “graphic depictions.” In many areas, the polemic even led to limited access to the public and schoolchildren. Unfortunately for detractors, though, the resulting buzz just made everyone more interested…!

CONTINUE TO PART 2

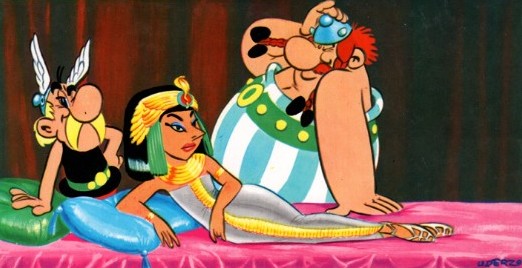

By Emma Wilson. Header image: Asterix and Cleopatra © 1968 Uderzo & Goscinny / Dargaud Films