Manu Larcenet. You utter that name in the corridors of any Franco-Belgian publishing house and practically everyone’s got something to say about it, comic book fans or not. Larcenet is easily one of the most celebrated artists of the 21st century, hailed as a genius by critics, collaborators and comics fans alike. His presence is as regular on prize lists as it is rare at media events. But this is an artist who has come a long way, with a past shrouded in anguish. He has now been involved in the industry as a professional for over 20 years. And he’s proud of what he’s achieved. According to Larcenet, it’s not a question of luck or chance, but simply the fact that his life’s intention has been to get where he is today.

Manu Larcenet. You utter that name in the corridors of any Franco-Belgian publishing house and practically everyone’s got something to say about it, comic book fans or not. Larcenet is easily one of the most celebrated artists of the 21st century, hailed as a genius by critics, collaborators and comics fans alike. His presence is as regular on prize lists as it is rare at media events. But this is an artist who has come a long way, with a past shrouded in anguish. He has now been involved in the industry as a professional for over 20 years. And he’s proud of what he’s achieved. According to Larcenet, it’s not a question of luck or chance, but simply the fact that his life’s intention has been to get where he is today.

Larcenet grew up in the suburbs of Paris. He was an awkward, solitary child. He dreaded going to school in the morning, he barely spoke, he had no friends, he didn’t play football; he’d just go home and draw. Art was a refuge from reality.

At around 12, he started sending photocopies of his drawings to various publishing houses. His emerging passion was nurtured by his middle school art teacher, who gave free lessons after class and helped him prepare for the entrance exam for a diploma in applied arts, which consisted of lots of drawing, architecture, pottery, upholstery and other such creative outlets.

Naturally, Larcenet’s parents had their reservations about their son’s pending career choices, for the obvious monetary reasons. His mother was an accountant and his father had an administrative role in a building and public works company. They both painted as a hobby, but neither had made art a vocation. Thankfully, Manu’s art teacher saved the day. When he met the young artist’s parents, he simply dismantled a pen and pointed out that each and every component had started out as a drawing. He was trying to convince them of the professional scope of an artistic qualification. He succeeded. Manu took the exam, he qualified, and he graduated. He originally wanted to be a graphic designer in an advertising agency, so he specialized in visual communications for his further studies. However, after a couple of internships in the industry, he was completely disillusioned.

He originally wanted to be a graphic designer in an advertising agency, so he specialized in visual communications for his further studies. However, after a couple of internships in the industry, he was completely disillusioned.

Years previously he had started a punk-rock band with school friends. Larcenet wrote lyrics, played guitar and sang. Around this time, things were picking up for them. They started giving more and more concerts in small venues around Paris. They eventually moved in to a squat together, and Larcenet devoted himself entirely to music and drawing. His drawings featured in several rock magazines and his band found a manager. In their last year together, the group played about 100 gigs in various small venues around Paris, and was the supporting act for up and coming punk bands. By the age of 20, Manu was heavily involved in the punk movement and far-left political activism with it. He watched his friends disappear one by one; they were either in prison, dead or just upped and left without a trace. He started to keep his distance, realizing that he was using political activism simply as an outlet for his anger. He suddenly decided to give up on the band just as they were about to record their first album. He was now free to dedicate himself wholeheartedly to comic books. He took up his studies again, which he also promptly gave up on (much to his father’s chagrin) and then, in 1994, he was offered a job by Gotlib at Fluide Glacial. He was 24.

Then everyone was after him: Spirou, Dupuis, Glénat… He was living the dream. In 1997, somewhere amongst the frenzy of his new-found success, he co-founded his own publishing house, whimsically named Les Rêveurs (The Dreamers) with his friend Nicolas Lebedel.

In 2000, he collaborated with Trondheim on the series Les Cosmonautes du Futur (2000-2004) for Dargaud’s Poisson Pilote collection, and then Les Entremondes (2003-2008) with his brother Patrice Larcenet. His alliance with Dargaud has proved a valuable one; it’s the publishing house with which he has produced some of his greatest work to date.

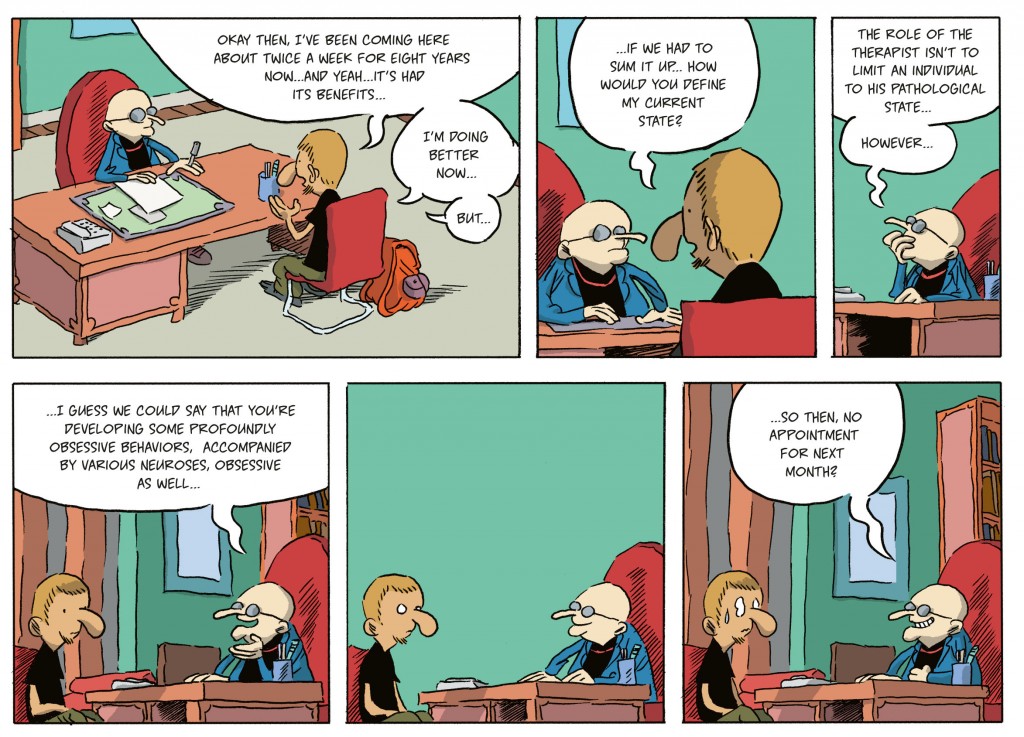

Meanwhile, in 2001, he left the city of lights and moved to the countryside. This marked a significant turning point in his life and would yield Le Retour à la terre (2002-2008, Dargaud, Back to Basics, Europe Comics, 2015-2016). This highly amusing series about urban exodus is elegantly scripted by Jean-Yves Ferri and features Larcenet himself as the main character. In 2003, a year into Le Retour à la terre, he also started working on the magnificent Combat Ordinaire (2003-2008, Dargaud, Ordinary Victories, Europe Comics, 2003-2008). This is the story of Marco (again, a kind of Larcenet; a city boy discovering life in the countryside), a young photographer vacillating between the highs and lows of family life. The series approaches difficult subjects with beautiful simplicity, punctuated with humor. Much to Manu’s surprise, Marco’s story won him the prize for best series at Angoulême festival, and universal public and critical acclaim. The series was adapted for cinema by Laurent Tuel in 2015.

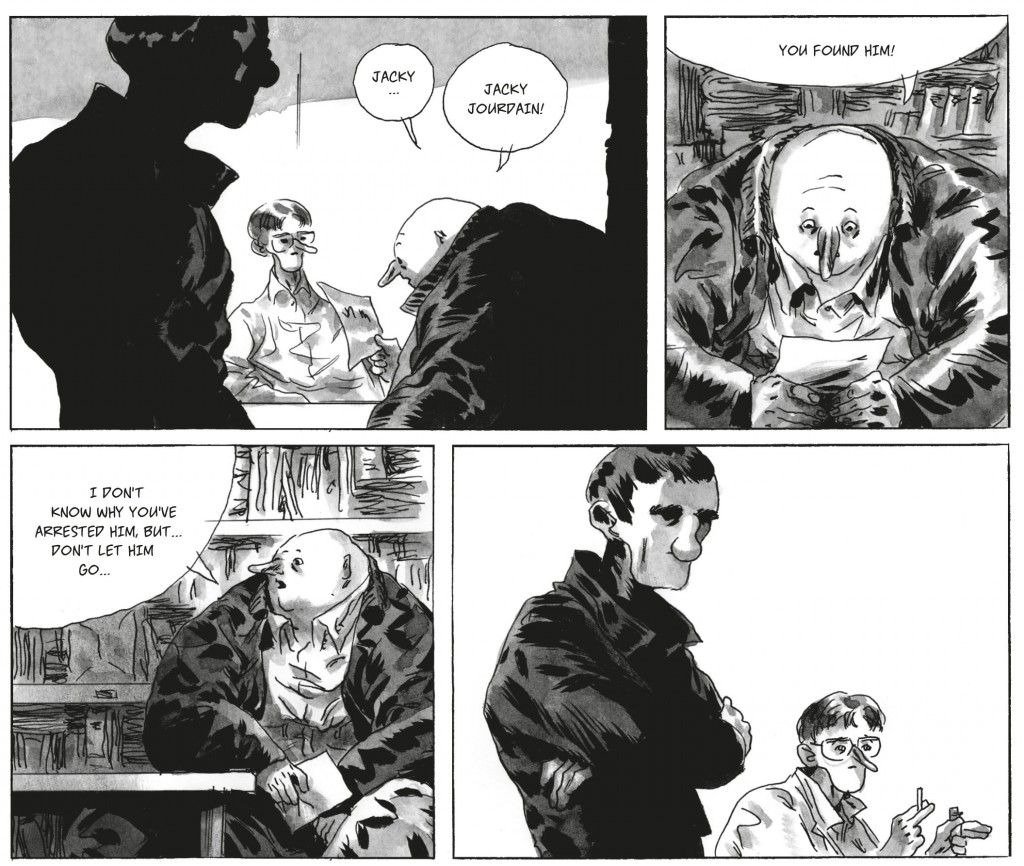

In 2009, things changed. Drastically. Blast happened. Blast is a four-part series bursting with lavish humanity and fascinating savagery. The narrative stems from a police interrogation of a clinically obese man accused of murder. The man has been living on the margins of society, his life momentum generated by his quest for “the blast,” a transcendent moment of absolute clarity. But what really is “the blast”? And what clicked in Larcenet’s mind to take him from the clever comedies that made his name to this terrifying plunge into the darkest depths of the human soul?

Since childhood, Larcenet has struggled with various psychological disorders, such as bipolarity and anxiety. In a rare interview for L’Express, he described a need to broach this aspect of his life: “Marginality, violence, madness, I needed to get it all out. Not to feel better, but to express myself.” So he stopped taking his medication, and he made Blast. The series ricochets between ecstasy and horror, the bucolic and the sordid, echoing the structure of bipolar disorder, and indeed whatever Larcenet’s state of mind happened to be on that particular day. It features some of the most violent scenes he’s ever illustrated. It is the graphical testament of the artist’s condition.

When he finished, he was completely burned out, but proud of what he’d achieved. It was the first time he’d ever felt truly satisfied with the end result of his work: “Blast is my masterpiece. I put all my pain into it.” The series, published by Dargaud between 2009-2014 (Europe Comics 2015-2016), won him several awards. Although he still suffers with psychological problems today, his family, regular therapy and drawing are his saving grace.

Larcenet felt it was time to do something new. After Blast, he couldn’t and didn’t want to write anymore. So he decided to adapt a novel. He chose Philippe Claudel’s Rapport de Brodeck (Brodeck’s Report, MacLehose Press, 2010) a novel about an artist’s arrival in a remote village, and the investigation into the subsequent acts of violence against him, provoked by nothing more than his dissimilarity. It’s a timeless portrait of the patterns of human group behavior in reaction to the outsider, as true today as it was during World War II.

As Manu read Claudel’s book, he found himself visualizing the panels. This project allowed him to focus entirely on the illustrations, without having to worry too much about the words. He avoided the trademark features of his previous work (the big nose, for example). Here, for the first time, he sought realism. There’s a sense of space and silence in Brodeck, with scenes of hunting, fishing, and the forest. Larcenet expresses distaste for the commotion of action movies and certain comic books, favoring instead a style that emphasizes the empty moments of daily life. Perhaps that’s what gives his work its distinctly truthful inflection. All of Larcenet’s heroes are mirror-images of himself in one way or another. His characters are etched from his own relationship with life and the self. For Larcenet, creativity is intimate. The self-portrait is inevitable. He seeks and shows imperfection. But with Anderer, the artist pariah in Rapport de Brodeck, he took it to another level. Anderer is different, marginalized, an outsider, alone against the crowd. Larcenet gave the artist his own face, and even a tattoo. He consciously and intentionally made Anderer his duplicate.

All of Larcenet’s heroes are mirror-images of himself in one way or another. His characters are etched from his own relationship with life and the self. For Larcenet, creativity is intimate. The self-portrait is inevitable. He seeks and shows imperfection. But with Anderer, the artist pariah in Rapport de Brodeck, he took it to another level. Anderer is different, marginalized, an outsider, alone against the crowd. Larcenet gave the artist his own face, and even a tattoo. He consciously and intentionally made Anderer his duplicate.

This stunning black and white adaptation was published by Dargaud in 2015, and the second volume a year later.

Although his central themes tend to remain the same (the outsider, facing the unknown, change, personal conflict), Larcenet’s graphic style differs from one project to the next. He experiments, he tries new things, he is not afraid of imperfection. After seven years working with the complex, somber hues of Blast and Brodeck, Larcenet has voiced an interest in the ‘ligne claire’ technique, pioneered by the likes of Hergé and Daniel Clowes. Now it’s just a question of finding the right story…

By Emma Wilson

Cover image from Blast © Manu Larcenet / Dargaud