By Pascal Ory

At the end of the day, we have to face the facts: it is impossible to write a history of “comics.” For the most recent period, one can write the history of the “9th art,” and this is done on a large scale. The term was coined in 1964, following the example of Ricciotto Canudo coining “7th art” half a century earlier. This model, moreover, makes sense: counterintuitively, but very understandably for whosoever is interested in national cultures, most of the modern “philias” were successively born in France, and not in the United States, in a vast movement to legitimize cultures that were born illegitimate to the old system of fine arts: cinéphilie in the 1920s, jazzophilie in the 1930s, and bédéphilie, the love of comics, in the 1960s.

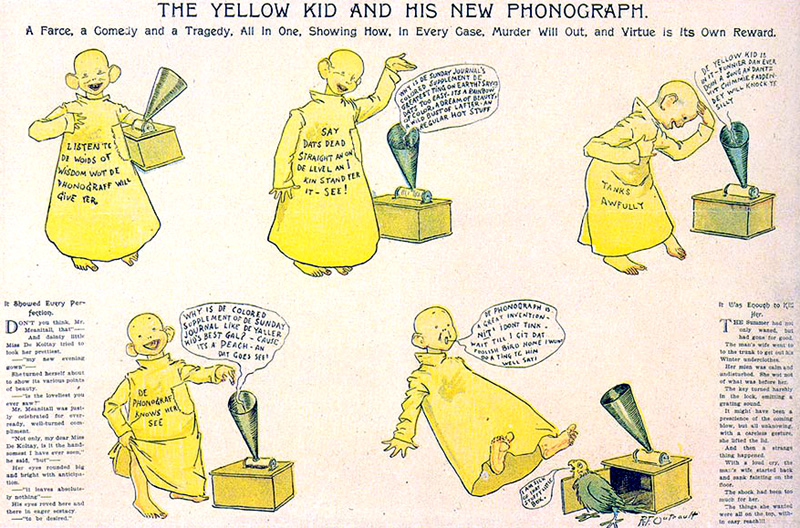

It so happens that the cultural traditions of this country have been more systematic and have gone further than those of any other country, first in building what might be called the “artist’s religion”—from the Enlightenment onwards—and then in legitimizing minor cultures, from Romanticism onwards. Thus, the Symbolist avant-garde, at the end of the 19th century, and the Surrealist avant-garde in the inter-war period, sought to magnify popular imagery, dime novels, circus acts, and dark humor. Those were the steps in which the first generation of comics artists followed, inventing the notion of the “Golden Age,” or the “Clear Line” school, for example, along with historians and critics, semiologists and sociologists, all outdoing one another in scholarly jousts and school quarrels. Towards the end of the 20th century, as discussions on the invention of the cinema were being stirred up again (Edison vs. the Lumière brothers, a debate that is foundational in every way), a similar debate arose regarding comics. From it emerged the fact that they had not been invented in the United States by Outcault or Dirks but in Switzerland, more than half a century earlier, by Rodolphe Töpffer.

That being so, where is the problem? Would this mean that, before the current era of the 9th art, there was a less noble era in which comics referred to a pre-artistic form? Well, not really. We now know through scholarly research—for the most meticulous erudition nowadays is often to be found in the deepest layers of mass culture—that surprisingly enough the French term for comics, bande dessinée, did not come into regular use until the early 1950s. To the best of current knowledge, it appeared, and then only as a hapax legomenon, on June 1st, 1938, in the national daily newspaper Le Populaire. It would then take another decade—until November 1949, to be precise—for it to reappear, this time in a regional daily newspaper, La Nouvelle république du Centre-Ouest. In other words, the legitimization process was all the more radical as, a dozen years before it even began (with the Club des bandes dessinées, founded in 1962 by Francis Lacassin, Alain Resnais and Chris Marker), what was going to enter the canon was still so low in the artistic hierarchy that there was no term for it. This had not been the case for photography, cinematography, jazz, and so forth. This art form literally had no name, whether noble or not. Understandably so, for half a century ago, those who are now known as comics artists were still just failed artists, working for “illustrated” magazines and drawing “little Mickeys.” It is hard to imagine more impediments: they were draftsmen rather than painters, illustrators of texts which they had not always authored, creators of pieces destined for “mechanical reproduction” rather than unique objects—and of figurations when abstraction triumphed—addressing a “young” or “working class” audience, and so on and so forth.

This founding paradox should be our starting point if we are to better understand this exemplary adventure: first, the fervor shown by the early cartoon lovers when they used the Lascaux cave and the Bayeux Tapestry or the stained-glass windows of cathedrals to trace the family tree of this invented art; and then the difficulty that persists to this day in the task of defining this art according to formal criteria: graphic expression literature, narrative figuration, figurative narration, sequential art, fun art? At this stage, let us just consider this turning point as the paradoxical sign of a dual modernity: the cinematograph was invented in 1895 and switched to sound in the late 1920s—in the Golden Age of comics—at the exact same time as these stories told in pictures spread in the now massively literate societies where the popular press and novels thrived, as an “audio-visual” form before the term was even coined. The reason for their success is surely to be found there.

This may satisfy those who seek explanatory factors for everything. But is it so important? Let’s face it, in history there are no causes, only effects. A technological change, an economic crisis, a political revolution make sense only if their effects on society come into consideration with some degree of hindsight. As with the cinema and with jazz, what is interesting about this vast undertaking to make stories in images respectable is above all its knock-on effect on the society of artists itself. It did not lower the bar for artists but, on the contrary, contributed to a continuous rise in authors’ graphic and literary emulation. They are now faced with a dual set of standards: those which a valued heritage sets, and those that come from the aesthetic confrontation with peers. This showed around the year 2000, for example, in the success of L’Association, a typical example of a “school” taking up the discourses and practices of the literary or graphic avant-gardes—in other words, of the modernist tradition.

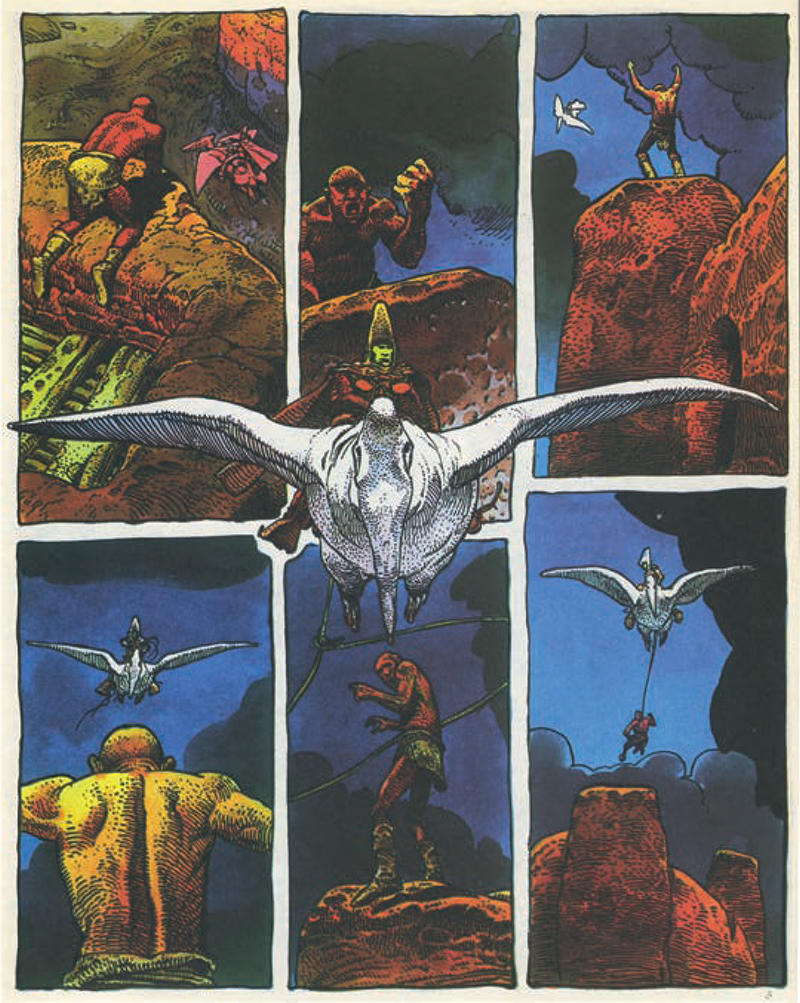

Let us add another reading to this specifically cultural dimension, a specifically national one. There is a reason why all the examples cited here were written in French. By structuring bédéphilie, the culture of comics, French culture was also able to assert itself as an international reference and, in turn, spread artistic recognition of its objects to lands that had previously been alien to this approach, such as Germany, Spain, or the United Kingdom. In the aftermath of the Second World War, American hegemony was expected to impose its standards on most of the planet, and Japanese manga is, paradoxically, the best proof of this, as a synthesis of American comics and of national graphic traditions. French culture’s ability to resist this hegemony can be explained by the combination of two mechanisms. The first—and most decisive—was cultural protectionism, mainly through the 1949 law on “publications intended for youths.” It was a moralizing law, and thereby secured the support of right-wing and left-wing bluenoses alike. It hindered the import of American productions, which were more open than European productions to the diversity of audiences. It therefore protected a French-speaking market on which the Belgian school could impose itself for a generation, using an effective combination of modern forms with conservative contents. It was within this protected market that, from the mid-1960s onwards, a new generation of authors took off. They were more radical than their predecessors, both graphically and in terms of scriptwriting. Around 1970, the periodical Pilote and others like it facilitated a transition from Belgium to France and, a few years later, the graphic novel, or roman graphique, was born simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic, freed from the constraints of serialized volumes. This was a decisive step towards making comics respectable. In the United States, graphic novels were to find a place on the shelves of bookshops, which until then had totally excluded comics—sold at newsstands—while French-speaking bookshops had been quick to integrate the Belgian school’s “albums.”

It was at this decisive time that two institutions were established in the French cultural landscape, both located in the town of Angoulême. From 1974 onwards, the annual comics festival—which, much like Cannes, became an international reference—and, some ten years later, the Cité pérenne, which materialized the great novelty of the 1980s: the 9th art had entered the remarkable circle of cultural policies, at national and local levels. In the late 20th century, with the momentum from this virtuous circle of recognition, French-language comics entered a world that had been foreign to them until then: the art market, where dynamism from the Belgian and French “civil societies” merges, as is evidenced by the accelerated development of specialized galleries and the growing place of comics-related objects in auctions.

The ultimate meaning of this success story reaches beyond national borders. Like any other prevailing situation—and proving those who see hegemony only as domination wrong—the French reference has led not towards closure but rather towards an opening to the outside world. As in many other artistic fields, there are many cartoonists of immigrant origin here (there is now, for example, an Indochinese school of French-language comics). More subtly still, it is through their contribution to France that certain great names in foreign comics have found their road to Damascus, as did Hugo Pratt, whose rise as an artist started when he entered the French cultural space. As in the field of gastronomic culture, where the emergence of great Spanish, English, or American chefs was based on the French model of the artist-chef and signature cuisine, a French model of the comic artist is now spreading throughout the world, invested with the same characteristics—and dare we say, the same privileges—as the artist of the modern tradition. The more comic artists are discussed, the more celebrated, inspired, and inspiring they are. Young graduates can now leave art school dreaming of becoming Moebius or Catherine Meurisse. The art without a name has been adopted by the family of fine arts, and Catherine Meurisse has been elected to the Académie.

Pascal Ory is a member of the Académie Française, historian, comic book critic, and co-editor of L’Art de la bande dessinée (Éditions Citadelles et Mazenod, 2012). Article first appeared in La lettre de l’Académie des beaux-arts issue n. 94, The Ninth Art: La bande dessinée à l’academie.

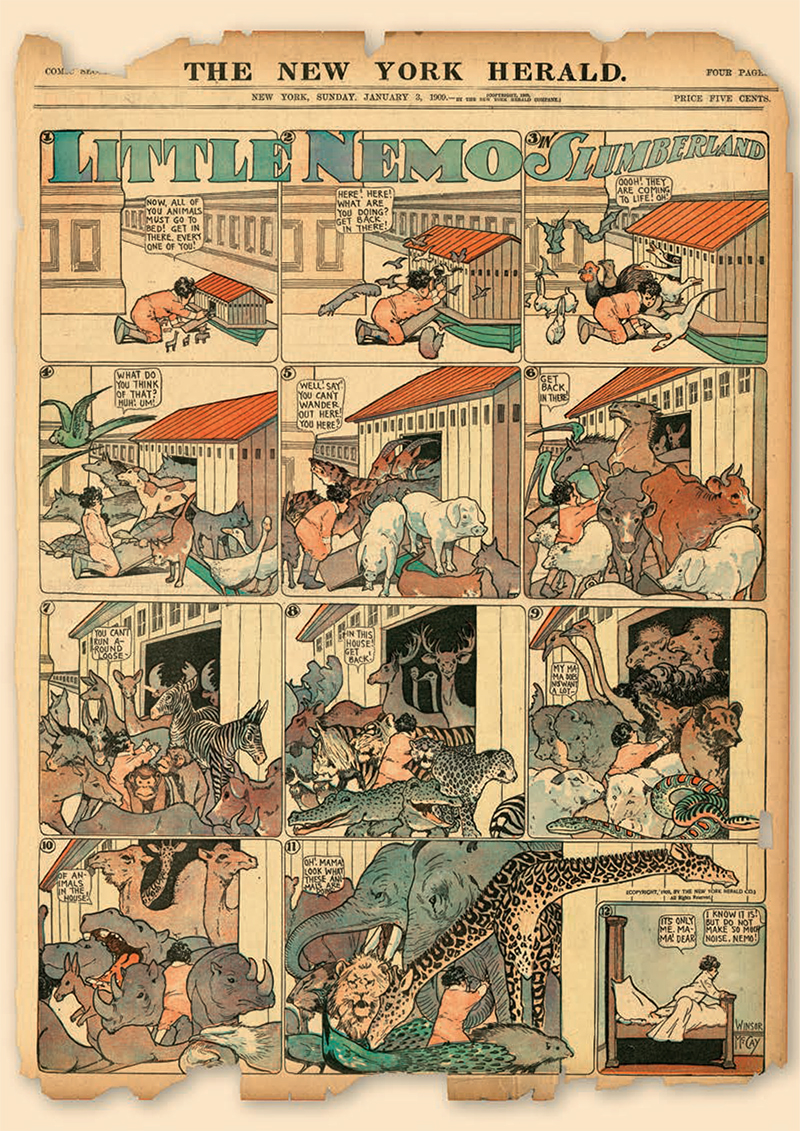

Hearder Image: Winsor McCay, Little Nemo in Slumberland, page four of the New York Herald, 8 January 1909. Old Paper Studios / Alamy