The following article has been excerpted from the anthology Heroes, Heroines, and Everything in Between: Challenging Gender and Sexuality Stereotypes in Children’s Entertainment Media.

Text by Dr. Annick Pellegrin.

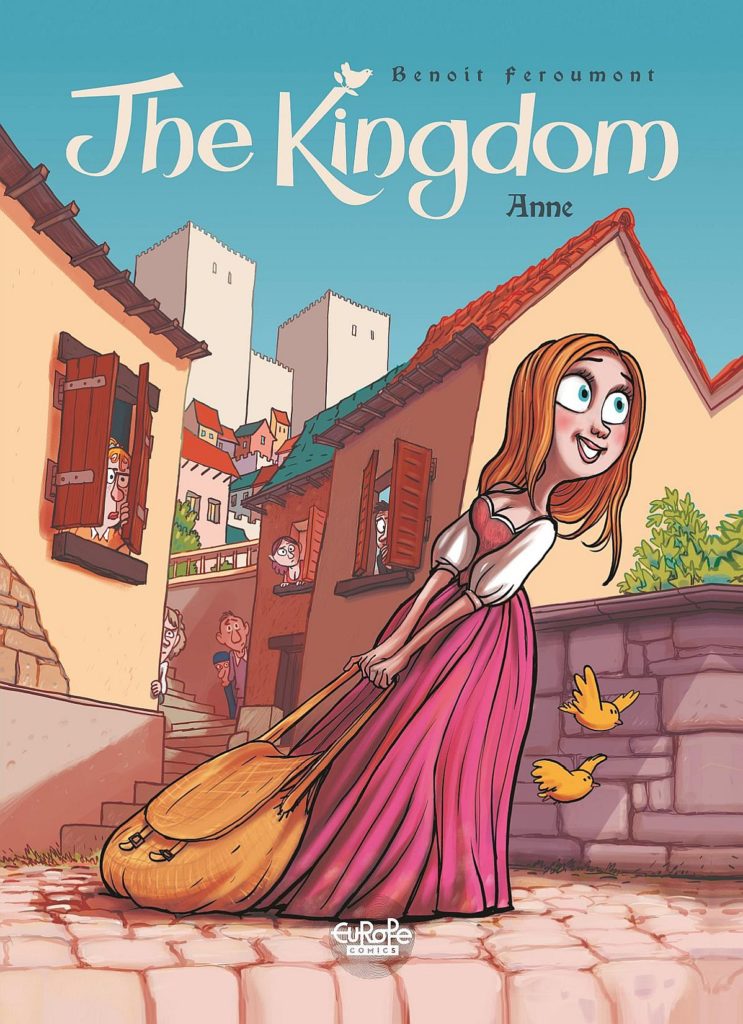

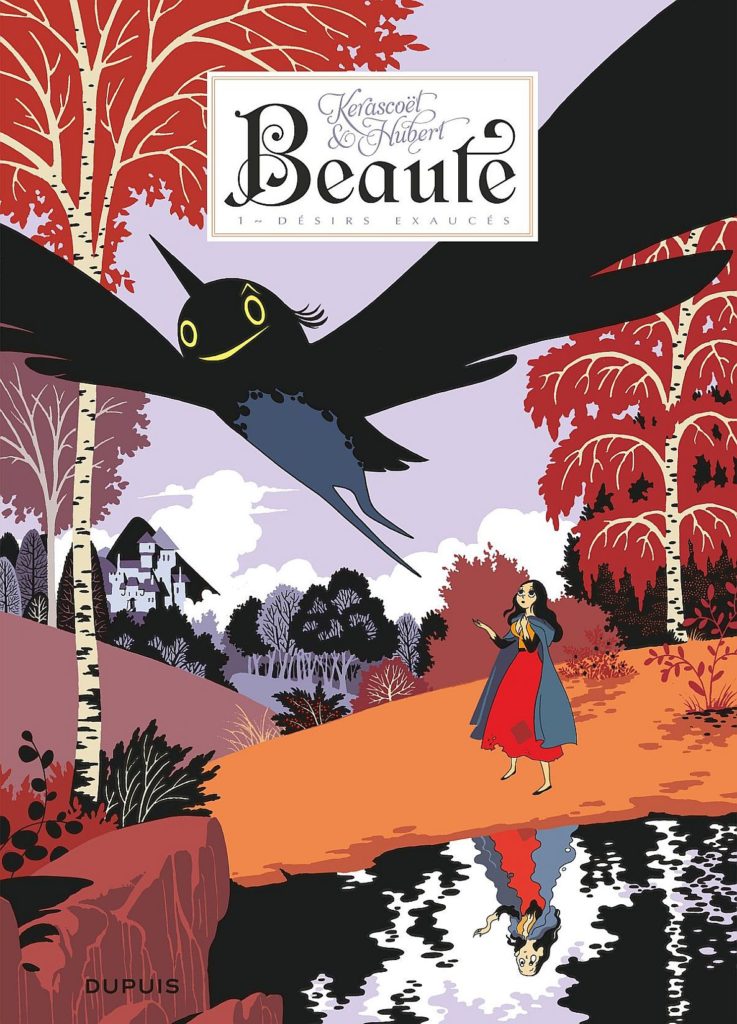

Although the beginnings of The Kingdom (Dupuis/Europe Comics) by Benoît Feroumont and Beauté (Dupuis; Beauty, NBM Publishing) by Hubert and Kerascoët seem to promise a traditional romantic fairy tale, both comic series in fact question the path to happiness promised by fairy tales and romance novels. They reveal that concepts like beauty, intelligence, and marriage often fail to guarantee a “happily ever after” ending. The first volume of Beauty closes on the poor and ugly peasant girl’s wedding to the king after she has become beautiful, but the next two volumes show what happens after the fairy-tale wedding: jealousy, madness, countless deaths, wars, and complete destruction of not one, but two kingdoms. As for Anne, the beautiful but poor maid in Le Royaume (the original French title of The Kingdom), she is dismissed from her job at the castle on suspicion of being the king’s mistress. Upon her return to the village, she soon meets François, the blacksmith, who falls in love with her at first sight and whose wedding proposals she rejects daily until she is forced to marry the villainous usurper to the crown, King Raoul, to save a child from mutilation (see vols. 1 and 5).

Many of the best-known fairy tales are of French origin, and France and Belgium share a very strong comics culture. Both fairy tales and traditional tous publics (literally, “all readerships” or family-oriented and for all ages) Franco-Belgian comics, or bandes dessinées, have often portrayed women in passive/submissive gender roles. Thus, such bandes dessinées have effectively educated young girls to adopt such traditional gender roles. Given this tendency, it is worth paying attention to these two works to analyze how the lead female characters challenge the fairytale “happily ever after” ending, as well as the idea of beauty and intelligence as a stepping-stone to happiness through marriage.

Before doing so, however, it is important to highlight the place given to women in the Franco-Belgian comics tradition. This overview is followed by an introduction that discusses the series, their plots, and their authors in more detail before analyzing the texts chosen. In many ways, the main characters Anne and Beauté break the mold of lead female characters routinely found in romantic fairy tales, romance novels, and comics. As heroines, they encourage readers to take on their attitude to life, and these works subvert the educational goals of traditional fairy tales and older bandes dessinées designed for girls.

The place of female characters in bandes dessinées

While much can be said about the target readership and the place of female authors of comic books, or on women in traditional romantic fairy tales and in romance novels, the scope of this article does not allow for much elaboration on these aspects. In regards to the place of female characters in bandes dessinées, one should bear in mind that shortly after the liberation of Europe — in 1949 — a law was passed in France that, without being exactly a censorship law, sought to protect young readers from content deemed immoral and from certain publications coming from overseas, especially from the United States.[1] Due to this law, there was a clear distinction between boys’ and girls’ magazines.

Before the postwar period, young readers were considered as minds that needed to be shaped, and girls’ magazines such as Mireille, Lisette, and La Semaine de Suzette taught young female readers their place in society: becoming housewives.[2] Starting in the fifties, female characters became more autonomous but were still stereotypical and few were heroines: they were mothers, friends, or foes of the male hero, and often irritating,[3] such as Bianca Castafiore (The Adventures of Tintin), whom everyone seeks to avoid; the journalist Seccotine (Spirou and Fantasio), a dangerous driver who does not know the meaning of street signs (see vol. 12, Le Nid des marsupilamis), and, from The Smurfs, the Smurfette, who, at first, is ugly and unintelligent. Smurfette was introduced as a Pandora of sorts, created by the sorcerer Gargamel specifically to provoke fights between the Smurfs, and she does cause many serious troubles in the Smurf village. Furthermore, she is only accepted by the others when she undergoes major plastic surgery (see vol. 3, La Schtroumpfette).[4]

Meanwhile, Yoko Tsuno (a young Japanese electronics engineer) and Natacha (an intelligent, autonomous, generous, blonde, curvy and doe-eyed flight attendant) were two of the first characters to offer a different image of women in bandes dessinées, insofar as they are the protagonists of their respective series.[5] Yet Yoko Tsuno, who is neither particularly sexy nor irritating, is something of an exception in bandes dessinées; as the comics journalist Hugues Dayez sums it up: “In reality, in traditional humoristic bandes dessinées, women were either sex bombs like Natacha, or dragons like La Castafiore.”[6]

The 1949 French law had a lasting effect on Belgian publications as well, because they could not be sold in France if they did not abide by its requirements.[7] To this day the great classic Franco-Belgian comics are still strongly marked by it, since they were originally created around that time and are still ongoing.[8] Important to this chapter’s discussion is Spirou magazine, created in April 1938 and owned by Dupuis; the publication is essentially the catalogue in which Dupuis prepublishes its family-oriented comics before publishing them in albums.[9] However, the magazine has changed over the decades, and one can now read works that deal with death (such as Seuls [Alone] by Vehlmann and Gazzotti), violence (such as Soda, by Warnant and Tome, then Gazzotti and Tome, and more recently Dan and Tome), love and sexual relationships between secondary school students (such as Tamara, by Darasse and Zidrou, later joined by Bosse and Lou), as well as homosexuality (such as Les Nombrils [The Bellybuttons] by Delaf and Dubuc). Because they deal with what would have been considered immoral topics, such series would never have been pre-published in Spirou or published by Dupuis previously.

The Kingdom and Beauté

First serialized in Spirou in 2008 and 2010, respectively, before being released in several forty-six-page albums, The Kingdom and Beauty are two comic series set in medieval times. The Kingdom is an ongoing series consisting of stories of varying lengths, not all of which are currently available in the published albums. Beauty, for its part, was originally published as three standard-length albums, followed by an epilogue in Spirou magazine (vol. #3949, Dec. 18, 2013). Although the English-language publisher of Beauty, NBM, classifies it as suitable for mature readers, the original publisher, Dupuis, considers it suitable for younger readers: it was pre-published in Spirou and subsequently listed as a 12+ series. Dupuis similarly classifies The Kingdom as suitable for all ages.

Anne, the main character of The Kingdom, is introduced waking up in the king’s bed: she spent the night there because she fears the owls’ hooting at night (see vol. 1). Anne may not be a princess, but her life in the castle was nonetheless a happy and sheltered one: she is very close to the royal children and received the same education as them (see vol. 3, and Best of BD numérique vol. 12). Anne’s fall from grace comes when some talking yellow birds tell the queen that she’s sleeping with the king. To make up for this sudden dismissal, the king gives Anne a house to turn into a tavern. Once Anne goes down into the village, she meets the talking birds, who anger her by spreading rumors about her having an affair with the king. As she chases them, she falls through a roof, onto the red-hot sword that François is forging. François instantly falls in love with her and promptly starts his habit of asking Anne to marry him. By the end of the first volume, the dynamics of the series have been established: Anne is an excellent cook and has a very popular tavern that hides a secret escape route from the castle; François wants to marry her and is extremely protective of her; she has taken in the talking birds; and the queen strongly dislikes her.

As for the main character of Beauté, her real name is unknown: initially, she is an ugly and poor girl who lives with her mother under her godmother’s roof. Ill-treated by all but her mother and her godmother’s son Pierre, she is known as Morue (Coddie) because of her smell: “By dint of scaling fish, the odor had penetrated Coddie’s skin so deeply that neither bath nor soap could make it go away. Coddie smelled of fish from sunrise to sunset, in winter as in summer” (vol. 1, p. 7, frames 8-9). As she sits by a pond, lamenting her lot in life, Coddie sheds a tear on an “ugly and misshapen” toad, thus unknowingly releasing the fairy Mab. In return for freeing her of her toad-like appearance, Mab casts a spell to change people’s perception of Coddie: “Beauty you want, beauty you will have. In the eyes of others, you will be the very idea of beauty in woman incarnate. Through this enchantment, you will eclipse the most lovely woman ever born” (vol. 1, p. 15, frames 6-7). The authors represent this rather particular spell by alternately showing Beauty’s real ugly looks and people’s perception of her as a beautiful woman. This gift turns out to be a curse as it drives men and women alike to jealous or lustful madness and even murder.

Do beauty and intelligence lead to happiness?

Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Snow White are three romantic fairy tales that place heavy emphasis on the physical beauty of their heroines. This physical beauty is supposed to reflect an inner beauty and offer a guarantee that the protagonist will find happiness in the form of a suitable match in age, social station, wealth, and beauty — that is, a dashing young prince.

For Coddie and Anne, it is their positions in their respective stories that demonstrate how they are different from characters like Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty. Initially, Coddie is not beautiful, intelligent, educated, or wealthy. To make matters worse, she is persecuted for her looks most of her life. Clearly sharing the ideals of romantic fairytale characters, she wishes for beauty because she believes it will eventually bring her happiness. Unfortunately, her good looks may well bring her even more grief than her true form. As soon as Coddie returns to her godmother’s home after receiving her gift, the men behave like animals in heat and she is almost gang-raped. Rather than seeking to help her, the women of the village accuse Coddie of irremediably tainting the men’s minds with her excessive beauty and attempt to burn her face to make her less attractive, to no visible effect because of Mab’s spell. Coddie is saved by the owner of these lands, Lord Eudes, who is instantly enthralled by her beauty, takes her in as his mistress, and changes her name to Beauty. This gory episode mixed with lust is the first in a long line of catastrophes caused by Coddie’s gift. Throughout the series men and women alike invariably lose their minds over her excessive apparent beauty, either killing themselves or each other in the case of men or seeking to harm her in the case of women. Moreover, even after she gains an education, Beauty is unable to find happiness. She may have a better understanding of the world, but that is not sufficient to put an end to the misery that men and women cause her.

As for the relatively poor Anne, she is both beautiful and intelligent, but she is not so beautiful that she drives men and women to madness. François is the only character who seems to lose all control and behave quite foolishly in Anne’s presence (see below). However, Anne’s intelligence is of a cunning kind that can enable her to stay or get out of trouble, though it also fails to bring her happiness as she uses her intelligence as much to help others as to manipulate them. For instance, while she will not accept François, she becomes very jealous when, encouraged by the birds, François decides to court Candice, his employer’s daughter, and she does everything she can to break up the couple. Once François turns his back on Candice, Anne states that she does not wish to get married and that she enjoys her freedom (see vol. 4). On the other hand, the king and the queen turn to her, the head of the queen’s army, and François when Princess Cécile is kidnapped, and Anne is the one to set up the rescue plan (see vol. 2).

Later, when the king’s unattractive advisor is bewitched and takes the appearance of the person one loves when kissed, Anne inadvertently reveals that she loves François but then denies it vehemently. When the advisor is finally relieved of the enchantment just as Candice tries to kiss him, and thereby prove her own love for François, Anne makes sure no one tells Candice the truth and enjoys her rival’s dismay. On the other hand, Anne is also able to resolve Princess Cécile’s first lovers’ quarrel with her betrothed as she realizes that each of them received an unrealistic and enhanced portrait of the other and reconciles them to avoid a war with the kingdom of Princess Cécile’s fiancé (see vol. 3).

Happily ever after, yes — married bliss, no

Despite the undeniable concerns with marriage, any possibility of married bliss seems to be thwarted when it comes to Anne and Beauty. Anne constantly and actively negates the idea that “a woman’s journey to happiness and fulfillment must always be undertaken in the company of a protective man,”[10] while Beauty’s obsession with married bliss cannot be fulfilled. Feroumont’s story never entirely clarifies whether Anne is the king’s mistress or if she only sought reassurance from a father figure; however, once she is alone, she learns to face her fears and there is clearly no room for the king as a lover in her life at this stage. The king tries to visit her on her first night in her new house through the secret passageway that directly connects his chambers to her kitchen. When he explains that he was hoping he could visit from time to time, Anne tells him squarely that he has a lot of nerve and sends him back to the castle, instructing him to use the main door like everybody else and informing him that the passageway will only be open if there is a siege (see vol. 1).

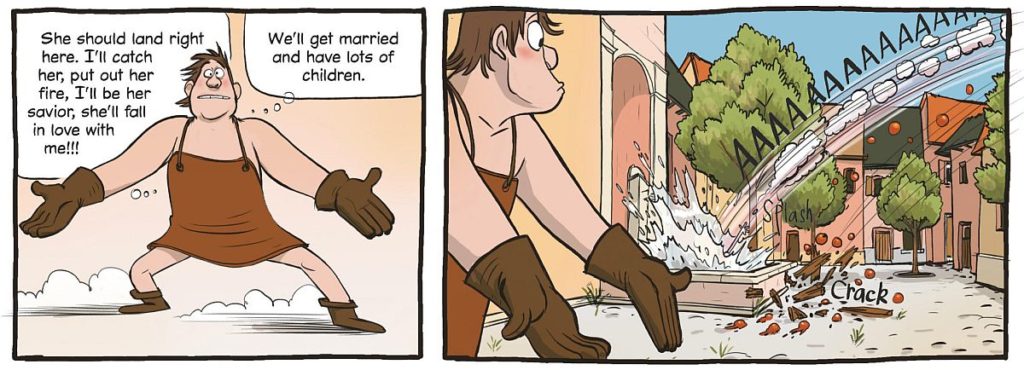

While François is more chivalrous than the king in his affection for Anne, he too believes that it is his right to claim her for himself. Although their first meeting is filled with slapstick humor, as Anne has a terrible cartwheeling fall all the way down the village and François tries to save her but completely fails, this is not the only reason to laugh here. Indeed, François is convinced that he will win her heart by saving her: “I’ll catch her, put out her fire, I’ll be her savior, she’ll fall in love with me!!! We’ll get married and have lots of children” (see below; vol. 1, ch. 2, p. 7). This assertion summarizes his idea of courtship and happiness. When he sees her next, he explains to her: “I’ve thought about this long and hard! There’s only one thing to do: you must marry me!!!” (vol. 1, ch. 4 p. 7, frame 4). He is very surprised when Anne refuses since to him this is the obvious outcome of their meeting, and there is no reason why Anne should have a say in the matter, unless it is a “yes.” Countless proposals later, he is shown insisting while Anne is working in the kitchen: “You will marry me, no doubt about it! … You’re young, you’re single, and you’re really pretty! You have to get married! It’s inevitable!” (vol. 5, p. 7, frame 1). While the outcome that François expects is a perfectly logical one in romantic fairy tales, in real life such a shortcut approach to falling in love, courting, and marrying is laughable in contemporary societies and cultures challenging patriarchal values.

Although Anne rejects François’s proposals daily, she is not insensitive to the opposite sex. Anne’s taste in men is based purely on appearance, and she is sensitive to bellâtres (bland pretty boys): from Jean-Michel, Anne’s first kiss and the head of the queen’s army (who proves to be a coward, liar, thief and traitor) [see vol. 2]; to Matteo di San Francesco, the “velvet troubadour,” who is followed by screaming and fainting female admirers but sings off-key and is an ungrateful snob (“Le Troubadour,” Mazaurette/Feroumont, Spirou #3865). While she happily flirts with Jean-Michel, she grovels before the troubadour, chasing after him in the rain and offering him her bed while she sleeps on the floor, although she quickly gives up and jumps in bed with the singer as she is too cold. While it is again unclear whether she engages in sexual intercourse with the singer, Anne clearly realized that giving up her own comfort for his was excessive; although, conversely, offering herself for sexual pleasure to someone who clearly looks down on her and has no interest in her as a person also seems like the ultimate form of groveling. Anne, however, comes to her senses in the end and loses patience with these men as she sees them for who they are: selfish, self-serving, pretentious, and superficial human beings. This does not prevent her from being superficial herself, however, for when her love for François is revealed when she kisses the bewitched king’s advisor, she asserts, “This brainless lump of muscle is not my idea of the perfect man!!!” (vol. 3, p. 32, frame 3).

While Anne rejects marriage as the ultimate goal or the natural outcome of any encounter with a person of the opposite sex, it is also clear that she considers herself above François and enjoys playing with his feelings. The story shows that Anne loves François, although she denies it (see vol. 3), but she does not seem to consider François as a suitable match for her: aside from her assertion regarding François’s body shape, when planning to go rescue the kidnapped Princess Cécile, she suggests that the king dress up as a merchant while she pretends to be his daughter and Jean-Michel’s wife (see vol. 2). Meanwhile, François is assigned the role of a servant, a configuration that everyone but François agrees is much more believable than Anne being François’s wife. Thus, it would seem Anne thinks it is irrelevant whether she is attracted to François or is in love with him, since neither his looks nor his social status meets her requirements. The only man she seems to consider marrying is a knight (another bellâtre), whom she does not love but who wants to bring her happiness (see vol. 5). Anne’s persistence in remaining single springs as much from a wish to stay free as from her conviction that François is simply not good enough for her.

As for Beauty, she initially has the same fairy-tale view of marriage as François. She is enthralled with marriage from the very beginning and she seeks her own traditional fairy-tale “happily ever after” time and again. A main cause for her grief is the fact that she has no marriage prospects. The children in the village offer her a fish for a fiancé, and she is considered too unattractive to be anyone’s dance partner, let alone May queen.[11] When she is saved and seduced by Lord Eudes, Beauty’s satisfied assertion is, “We should stay like this forever” (Beauty, NBM, p. 28, frame 1). This idea sums up her view of happiness: two people who are comfortably huddled up together, away from the world.

Beauty is unable to reconcile her fairy-tale idea of romantic happiness with the real world, and the trouble starts immediately as Lord Eudes needs to go hunting and she is unable to exist as her own person, outside of the couple. She begins to throw tantrums and expects expensive tokens of love and, encouraged by Mab, she eventually pushes Lord Eudes away, convinced that she deserves someone who has more money. When she is introduced to King Maxence, Beauty’s thirst for married bliss with a man with a high social status is even stronger. Although she does not know him, she knows that he is “the man of her dreams. She has to have him” (p. 43, frame 5). Their royal wedding seems like a fairy-tale ending to Beauty’s rags-to-riches path in life, but it is only the conclusion to the first part of a triptych: as Hubert puts it, the second installment “starts with the usual ending of all fairy tales” (Spirou #3814, May 18 2011). Hubert and Kerascoët paint a less than perfect picture: they bring to light Beauty’s naiveté in believing that marriage is a magical solution to all the woes in the world.

When beauty and brains are not enough

While Beauty’s naive wish for beauty as a stepping stone to a fairy-tale “happily ever after” brings about the destruction of two entire kingdoms, by the end of the triptych, she is a better person than Anne. Indeed, Anne does learn to become strong and independent, but she is still a manipulative and superficial person when it comes to relationships.

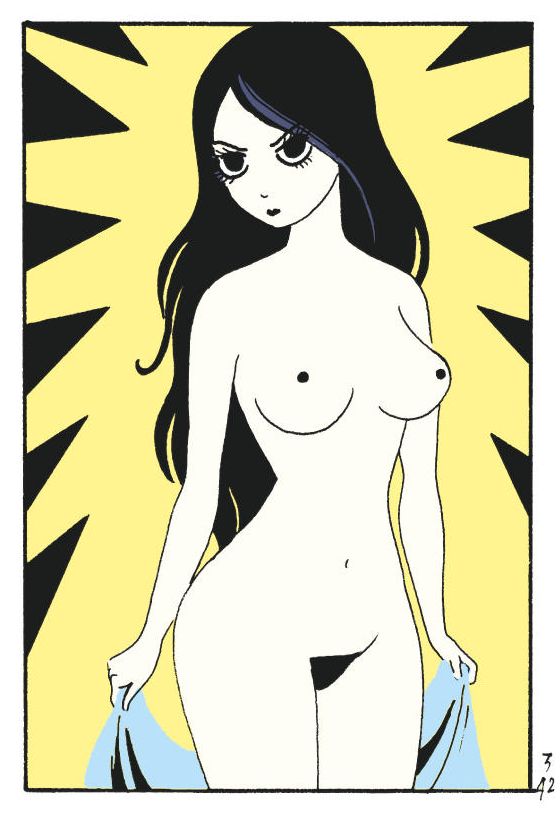

As a captive, Beauty experiences even more torment, and it is only when she can free herself from men and their desire for her that she can find peace. When the Northern Queen sets out to kill her using a large army, Beauty decides to use her only weapon and presents herself naked in front of the Northern army. Stunned by her beauty and the determination in her eyes, the soldiers turn against the Northern Queen and kill the latter. Beauty takes power and is followed by “an endlessly growing army adoring her on its knees” (p. 143, frame 1). Beauty then conquers both the Northern and the Southern Kingdoms and walls up all the fairies. From then on, Beauty reigns unchallenged.

Beauty’s seduction, however, is different now. Indeed, it is her strength and determination that “filled [the first soldier who saw her stark naked] with a sacred terror. Imagining laying a hand on her seemed like an intolerable sacrilege. [ … ] Nobody saw her anymore as a woman of flesh and blood but as a supernatural being. Nobody would have dared lay a hand on her for fear of being instantly struck down” (p. 142, frames 2-3). Beyond becoming something of a goddess in the eyes of others, Beauty also finds both her own strength and wisdom. It is not her physical appearance, but the inner strength expressed in her gaze that submits armies of men from the Northern and the Southern kingdoms, when she stops living in fear or with naive ideas about romantic fairy tales (see below). From then on, she can rule as a fair and wise sovereign capable of freeing the kingdom from the tyranny of fairies.

Anne may be a strong independent woman with a cunning intelligence, but she does not yet have Beauty’s wisdom as she continues to be fooled by the looks of pretty boys and to toy with François’s feelings. Anne cannot see François’s inner beauty, which leads her to continually reject his admiration and loyalty, and all the while she seeks out the same from men who will never care for her. Anne may have started in a better position than Beauty for intelligence and physical appearance, but she has not yet learned that the ideal “happily ever after” is not possible. Because of the wisdom she gains through her ordeals, Beauty has learned this moral.

Thus, neither Anne’s nor Beauty’s characters deny that “happily ever after” is a goal that can be reached. However, whether this “happily ever after” means “ils se marièrent et eurent beaucoup d’enfants” (“they got married and had many children,” which is the traditional conclusion to romantic fairy tales in French) is uncertain. In the case of Beauty, marriage and any involvement with men bring her nothing but pain. The birth of an unattractive daughter later on marks the beginning of her husband’s doubts, as well as serious trouble in the marriage and within the kingdom as the king begins to kill everyone around him in jealous fits. When the tale closes, she has reached happiness on an ethereal plane, far removed from her idea of happiness when she first met Lord Eudes. She did indeed get the prince’s castle but did not serve as a trophy wife. Moreover, rather than seek self-gratifying material pleasures, she learns to show concern for the well-being of her kingdom as a whole, having understood that being a true sovereign is more about serving others rather than being served.

As for Anne, the nature of the series makes it more difficult to pronounce what a “happily ever after” might look like for her. Indeed, while Beauty is a triptych that has a clear beginning and a clear end, The Kingdom is an ongoing series that, at the time of this publication, does not have a clearly thought-out plan for a set number of albums to tell a given story with a definitive conclusion. However, Anne’s happiness clearly does not depend on her being married from the very beginning, as Beauty’s idea of happiness did. Anne may be scared to live on her own at first, but she values her independence and cannot understand François’s conviction that she simply must get married, whether it is to him or to someone else. As for her forced marriage to King Raoul, it can hardly be said to bring her happiness (see below), and every vow she pronounces at the altar is peppered with ill wishes for this man. Thus, she may consider that François is beneath her station, but it is also clear that, unlike the ambitious Candice, marrying into royalty is not Anne’s goal in life, and she is not easily swayed by the glow of power and wealth.

Conclusion

Neither Coddie/Beauty nor Anne is different from fairy-tale heroines as far as their appearance is concerned, as the comics depict them both as beautiful young women in large gowns. Additionally, they are not blind to Prince Charming’s good looks, neither are they insensitive to social status. However, they both learn to assert themselves as strong, independent heroines who do not need a protective husband to be happy. They are, or become, educated and succeed in challenging traditions because they learn to stand up to anyone who tries to impose their sexual whims and demands on them. And in so doing, they succeed in taking control of their own lives.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Ory, Pascal. 1984. “Mickey Go Home!: La Désamericanisation de la bande dessinée (1945-1950).” Vingtième Siècle: Revue d’histoire 4: 77-88.

[2] Ternaux, Catherine. 2001. “Le Rédactionnel dans la presse pour jeunes filles.” Neuvième Art 6. https://neuviemeart.citebd.org/spip.php?articlel03

[3] Renoux, Jean-Philippe, and Olivier Thierry. 2010. “Natacha et Yoko Tsuno: deux quadras en pleine forme.” Zoo, March-April. https://zoo-bd.typepad.com/zoo-le-mag/magazines/Z00-24-BD.pdf

[4] Buéno, Antoine. 2013. Le Petit Livre bleu: Les schtroumpfs sont-ils misogynes, communistes ou nazis? Paris: Pocket.

[5] Renoux and Thierry, 2010.

[6] Feroumont. 2016. “Benoît Feroumont: ‘Ici, je me sens plus proche d’Hergé que de Franquin!”‘ By H. Dayez. Spirou, April 6.

[7] Ory, 1984.

[8] Pellegrin, Annick. 2014. ‘”I Knew Killing a Man Would Kill You’: Lucky Luke Shaped by Myth and History.” Transformations (24: The Other Western). https://www.transformationsjournal.org/issue-24/.

[9] “Albums” in this context are usually A4-sized, portrait-oriented, hardcover volumes of approximately 48 pages, comprising single-page comics, short stories, or a complete adventure of a given series.

[10] Radway, Janice A. 1983. “Women Read the Romance: The Interaction of Text and Context.” Feminist Studies 9 (1): 53-78.

[11] The May queen is chosen by the local noble gentleman to spend a night with him. This is considered an honor in the village, and the girl who is chosen at the party shown in the story is showered with gifts and receives money (presumably in compensation for her virginity) that makes it possible for her to marry the boy she loves. While this practice is hardly respectful of women as human beings, the fact that she will never be beautiful enough for a noble to even consider her as a bedfellow for a night is the cause of much chagrin for Beauty.

This text is dedicated to the Phoenix.

— Dr. Annick Pellegrin

Copyright Lexington Books; reproduced with the permission of the publisher.

Header image: The Kingdom © Feroumont / Dupuis