by Laurent Mélikian

Will Eisner is renowned as the father of the graphic novel. Eisner was in large part pushed to give comics a more literary bent by the illustrated stories popular in Europe in the 1930s, especially the work of Flemish engraver Frans Masereel. Has Europe now managed to reclaim the graphic novel? We carry on our series by passing through Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Great Britain, places visited again and again by Masereel.

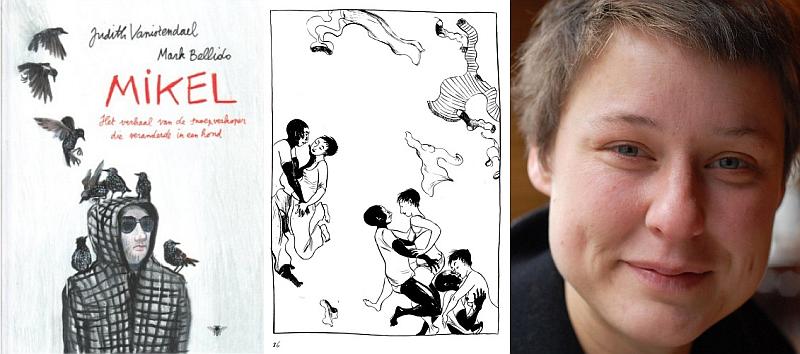

Judith Vanistendael: Embracing duality

Brussels, a dual capital with dual languages, is the home of 45-year-old Judith Vanistendael, an emerging voice in Flemish comics. She cites Gaston Lagaffe (Dupuis; Gomer Goof, Cinebook) and Suske en Wiske (Spike and Suzy) as having most marked her as a child and agrees about the existence of a cultural duality in her community: “In Belgium, the Flemish and French-speaking worlds are totally separate. The Flemish gravitate towards the English-speaking world, and the French-speaking population leans towards France. I’ve been lucky in that I’ve been able to publish in both languages.”

And she works in a medium as vast as the continent she inhabits: “I live in Europe, which allows for freedom of movement,” affirms Vanistendael. “I recently published a story about the Basque Country, which would not have been possible if I hadn’t studied in Spain under the EU’s Erasmus program. What’s more, I first found love because of the Dublin Convention, which obliges refugees to apply for asylum in the European country of arrival. Abou came from Togo, arriving first in Belgium. He wanted to settle in Germany but had to stay in Brussels where we met… This experience ended up being the subject of my thesis. De Maagd en de Neger (“The Young Girl and the Black Man”) caught the interest of a Dutch publisher and launched my career as an author.” The fact that her works have been translated into half a dozen languages has not taken away from her Flemish identity. Her graphic novel Mikel, a story about a Basque bodyguard protecting an elected official from threats made by the independence movement ETA, is not far removed from Belgian reality: “For the Flemish, any independence movement resonates with their own concerns. We’re familiar with ETA, while on the other side, the Basques know that there is also a Flemish influence in Brussels…”

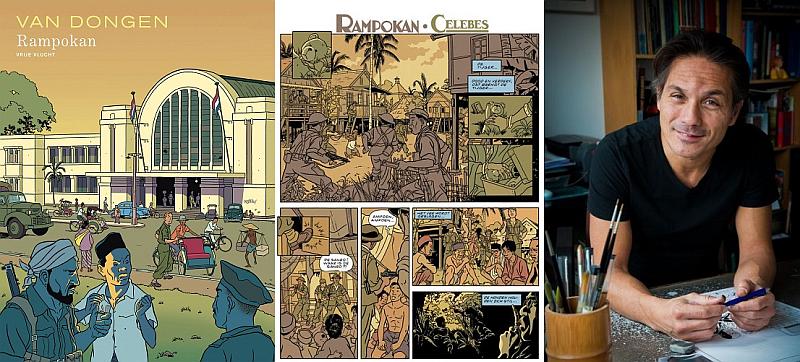

Peter van Dongen: Unraveling colonialism

Similar to Judith Vanistendael, other authors we spoke with found themselves working on themes that crossed borders. One of Europe’s first contemporary graphic novel creators, Peter van Dongen, is Dutch. In 1998, he published Rampokan (Dupuis; Europe Comics 2019) in which he recounted the demise of the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia, where his mother is from). The fifty-year-old has just finished sketching the latest episode of the adventures of Blake & Mortimer. He too creates with a continental point of view: “At seven or eight years old, my mother told me that Holland was part of Europe. I suddenly realized that our nations were connected, and I felt an intense solidarity between our states. At the time, the Cold War was still underway. When I write a story,” he says, “I speak to readers far beyond the Netherlands. Rampokan tackles the history of decolonization, a process that most of the major European countries have gone through. This was made clear when the book was published in French. A young man of African origin I was speaking with at the Angoulême comics festival told me he’d seen himself in my Indonesian characters!” Van Dongen has emerged as a virtuoso artist, a worthy successor to Hergé in his way of telling a tale: “In Rampokan, I was able to insert a kind of Belgian influence. I used the Tintin archetypes to cast a new perspective on colonization…”

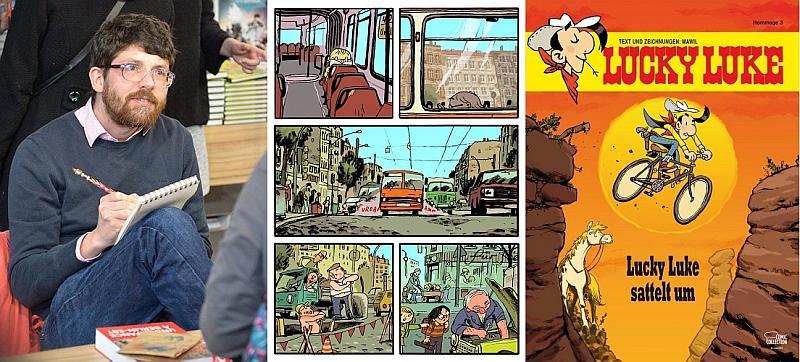

Mawil: East of the Wall

Further east, much of Germany shares memories of the Soviet era with Eastern Europe. “I was born in East Germany,” recalls Mawil, a Berlin artist born in 1976. “Comics were rare, with the exception of those in a magazine called Mosaïk. When I could, I read Franco-Belgian albums like Asterix, lent by friends. I noticed certain differences between these and the comics published in magazines. As I read and re-read them, new things would emerge every single time. I also liked the children’s books from the East, which were of high quality, and became a form of escape.” Much like Marzena Sowa in Poland (see part one), Mawil tells the story of his childhood under the Communist regime. In Kinderland, a graphic novel that is partially autobiographical, the demise of the Soviet bloc disrupts a ping-pong tournament between college students. “Readers from Eastern Germany have said that they could see themselves in this book, as have Russians and Poles. Many details go over the heads of those who didn’t grow up on this side of the wall.” Following the publication of Kinderland in several languages, Mawil switched track and surprised everyone by creating Lucky Luke Saddles Up (Egmont Germany; Europe Comics in English), his take on the humorous cowboy created by Morris in 1946 in Brussels. “The release of the book was highly publicized and I was very happy to present this character in my own way. Many Germans consider Lucky Luke to be American, whereas for me, he’s a typical European hero. “

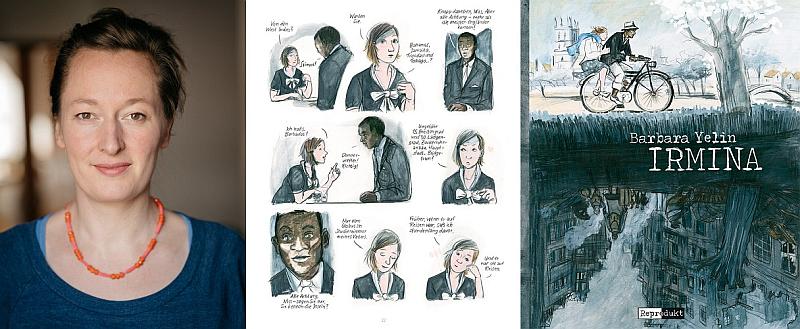

Barbarba Yelin: Exorcising the past

Another contemporary graphic novelist has succeeded in capturing German and European memories through her work. Barbara Yelin, born in 1976, sought to find out how her own grandmother, a free, independent, and progressive young woman, became entangled with the Nazi regime. Irmina (Reprodukt; SelfMadeHero in English), named after Yelin’s grandmother, is a fascinating 300-page tale that was published in German and French in 2014. It has since been translated into a dozen or so languages. “I recently went to Spain, where it had just been published,” says Yelin. “They, too, have a fascist past. The readers I met were interested in the theme of complicity in dictatorship, it’s a subject that we have in common.” Yelin has now been publishing graphic novels for 15 years. “My first book was commissioned by L’An 2, a French publishing house. I met the director, Thierry Groensteen, at a small festival in Germany. I have gained so much from the culture of European comics.”

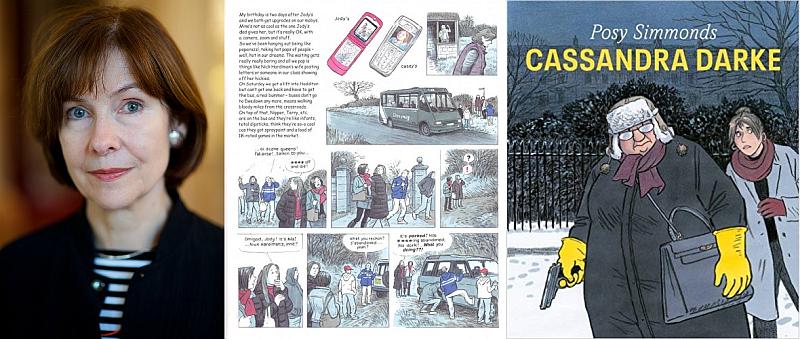

Posy Simmonds: Bridging genres

While the issue of Brexit remains unresolved, well-known British author Posy Simmonds shared her thoughts on the medium today: “The graphic novel is absolutely European, because it’s a democratic means of expression. Anyone can use it, be it dinosaurs like me, or young people publishing online!” Gemma Bovery, Tamara Drewe, and Cassandra Darke are three titles in which she shakes up the rules of the genre, merging the comics form with lengthy written passages in a contemporary reinterpretation of the literary classics. “Gemma Bovery allowed me to bring my fascination with Flaubert’s novel to life,” she recalls. “I had read Madame Bovary in French at the age of 15, with the help of a massive dictionary. Before I even went to France, I immersed myself in French literature, poetry, and art. This is how I actually began to feel European, given that in my country, our visual culture is probably weaker than our literature.”

In Great Britain, Posy Simmonds is a leading newspaper cartoonist as well as children’s book writer. Her graphic novels, which she’s been publishing since 1997, have been adapted into films in France and the UK, as well as being translated into German, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, and Korean. “My children’s books were first published in France in the 1980s. I was amazed to see so many adults in France standing around in bookstores reading comic books. I decided to do the same, and started meeting authors. When Gemma Bovery was published, I finally felt like I had become part of this big family, little old me who just drew for the papers… ”

In part three, our European journey will wrap up with a visit around the Mediterranean.

Published in collaboration with ActuaBD.com (article in French here). Text by Laurent Mélikian, journalist and international comics specialist.

Header image: Lucky Luke Saddles Up © Mawil / Egmont Germany