Asterix, or Astérix le Gaulois in its original version, is undoubtedly one of the cornerstones of the international comics scene. Since its first publication in Pilote magazine in 1959, it has been translated into more than 100 languages, with over 375 million copies sold worldwide. Already by the mid 1970s, the fame of the little Gallic hero had reached every corner of Europe, and was destined to go even beyond the borders of the Roman Empire.

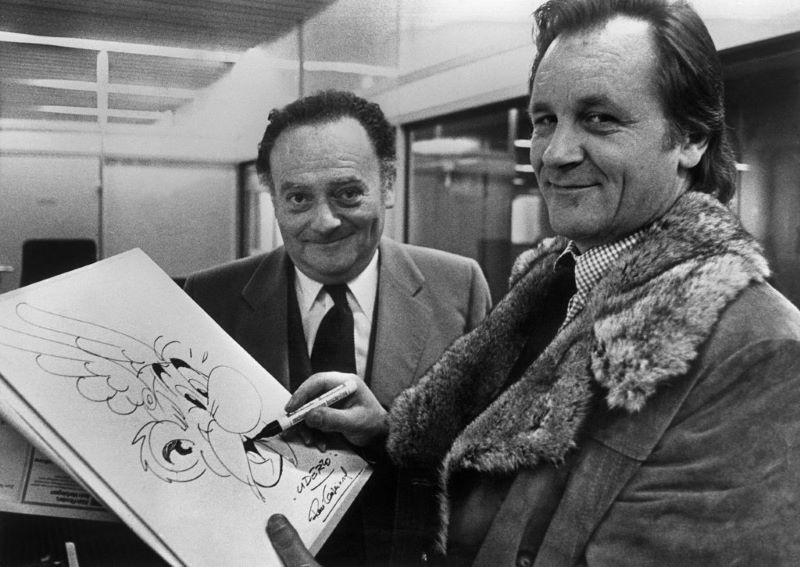

Our story begins in Brussels in the offices of World Press, a division of the International Press specialized in illustrated content. It was here in 1951 that Albert Uderzo and René Goscinny met for the first time, and eight years later, on 29 October 1959, Asterix and Obelix came to life on printed paper. The success of the first stories (Astérix le Gaulois, 1959, La Serpe d’or, 1960 and Astérix et le Goths, 1961) was so great that in 1961 the episodes published in Pilote were collected and published in album form, which in that year sold over 6000 copies.

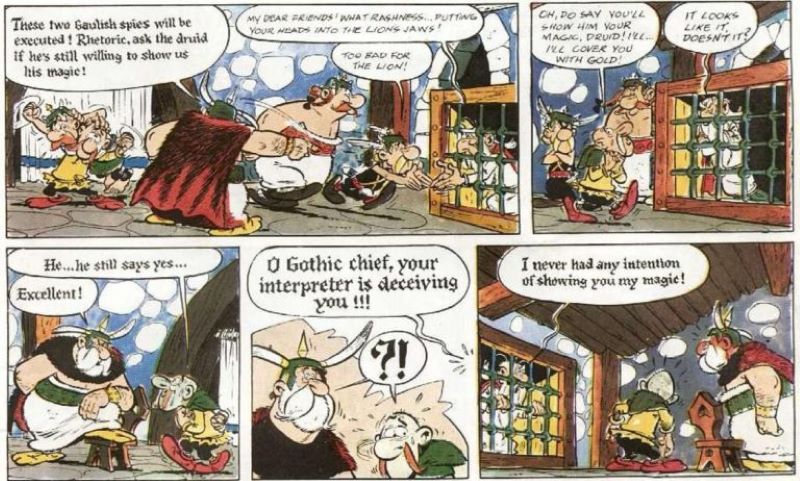

It was again in 1961, with Astérix et les Goths, that Asterix and Obelix ventured outside Gaul for the first time, crossing the border into Germany. In the following years the heroic Gauls visited England (Astérix chez les Bretons, 1966), Spain (Astérix en Hispaine, 1969), Belgium (Astérix chez les Belges, 1979), Italy (Astérix et le transitalique, 2017) and many other countries – they even arrived in America in La Grande Traversée (1975).

From France to the whole world

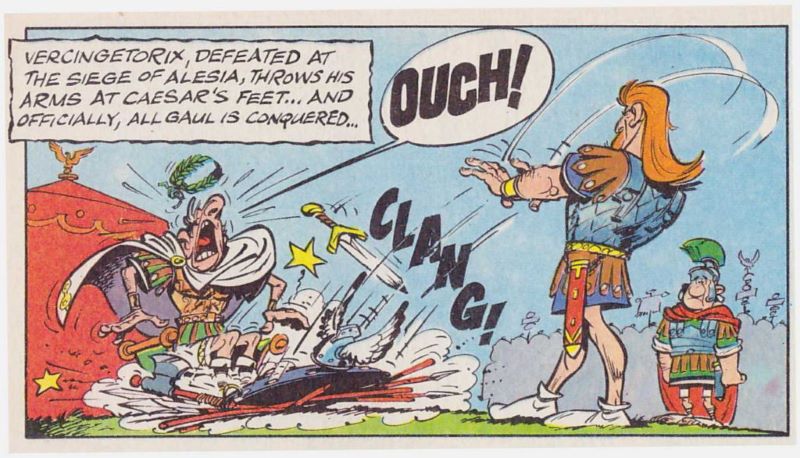

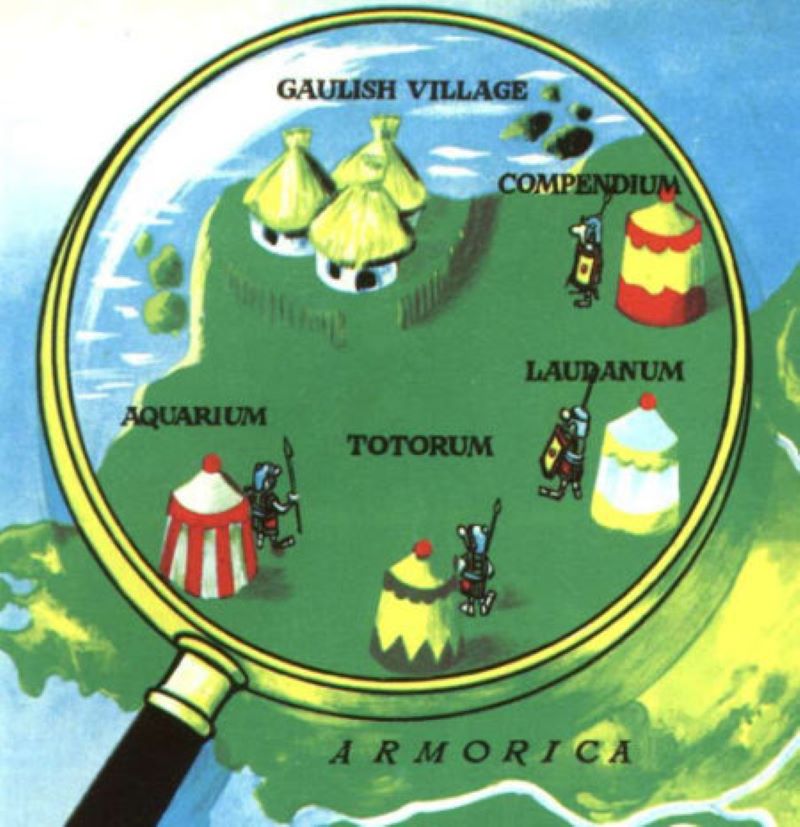

The idea at the start was to create a comic strip that would tie in with France’s historical roots: “Let’s take a look at the past: give me the great stages of our history,” René told his friend Albert. In fact, one of the first images shown to us in the series is the legendary surrender of Vercingetorix to Caesar. Immediately afterwards, however, the two artists take us to a small Gaulish village, which (at least until 1959) was not in any history book. The village, located in the north-western part of France, is shown at the beginning of each volume and creates little doubt about its geographical location.

Thanks to the testimony of Uderzo himself, we can say with confidence that the village in Armorica finds its real counterpart in the coastal town of Erquy, in present-day Brittany. During an interview for AFP (Agence France-Presse), the illustrator declared that he had “unconsciously taken this town as a model” for the design of the village. After finding refuge there with his brother during the Second World War, Uderzo could not help but be fascinated by the landscape of Erquy and then transpose it into his work.

Although the village of Asterix and Obelix is a product of his imagination (and his hand), it has several easily identifiable elements in the Armorican Coast: the three stones of the promontory, the quarries of the town where Obelix works his menhirs, or the beaches shown in Le domaine des Dieux (1971). These, together with other small details inserted more or less consciously among the cartoons of Uderzo, reinforce the reak-world foundation of the story’s setting.

Though similarities can also be found in the customs and habits of the Bretons of the Roman era, we cannot say the same with regard to the warrior attitude. In the history of Erquy there is no trace of any heroic resistance, to the point that history books report the presence of a Roman camp on the promontory dating back to the Iron Age. Is there, then, a real counterpart to the strength and legendary courage of the Gauls? Well, yes, although not in France, and unfortunately declined to the harsh laws of reality.

Iberian city, Gaul heart

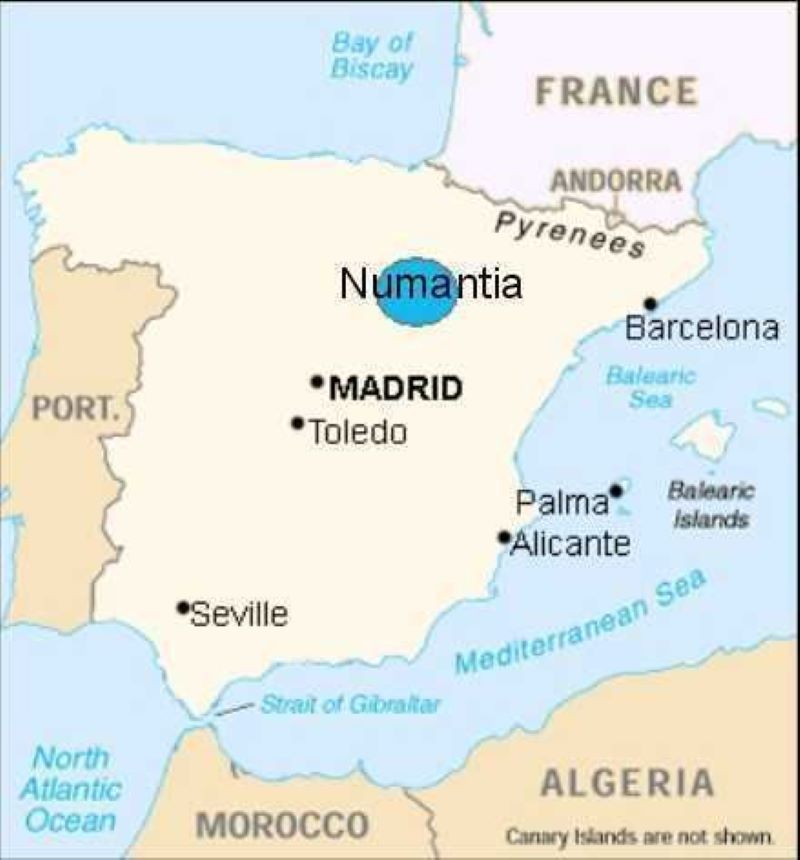

In order to find it, we have to go 1200 kilometres further south and turn back our clock (or sundial in this case) of about 100 years, going from 50 BC (when Asterix’ adventures are set) to 153 BC. On this date, in the current Spanish province of Soria, a small village in the hills obtained its first victory against the Roman invader. It was the small town of Numantia, a Celtiberian stronghold whose history bears a striking resemblance to that of the Armorican village of Asterix. In the 20 years following that first victory and beyond, the Romans will associate the word “defeat” with the name of Numantia, just as Julius Caesar resigned himself to doing with Asterix.

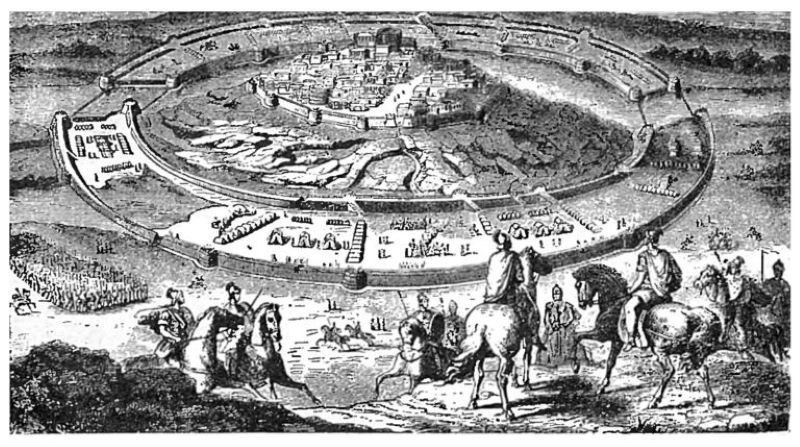

The history of the city of Numantia is famous for the circumstances of the long conflict with Rome that took place between 153 and 133 BC. From the day of their first victory, the roughly 4,000 Numantians barricaded within a perimeter of “more or less 900 metres with a fortified tower” held out against five assaults and over 60,000 Roman soldiers before being defeated by the imperial colossus.

The Roman historian Floro compares them to Carthage and Corinth for their sense of freedom and resistance, so similar to that of the indomitable Gauls. The Indo-European people (Celtiberians to be precise) also shared with the Gauls of Uderzo and Goscinny (the Celts’ counterpart) the same social organization, based on the concept of patriarchy, clans and tribes. At the top of the society was the warrior class, although there is no evidence that they carried their leader on a shield here and there around the village.

Another historian, the Hispano-Roman priest Paulo Orosio, gives us interesting insights into Numantian habits. In his work Historiarium adversus paganos (418 A.D.) he tells us about Numantia’s heroic resistance, but a certain detail stands out. In describing the preparations for the battle, Orosio cites a particular drink called caelia – from the verb calentar, to warm up – with “a rough taste and inebriating heat.” Together with the process of preparation, the historian describes how the Numantians were launched to the charge “burned by this drink” when they charged their enemy, having consumed huge quantities of it.

More similar to beer than to the potion of Panoramix, we do not know whether the effects of the two drinks were the same. What we do know is that this was ultimately not enough for the Numantians to resist the cruel Roman tactics. In fact, among the various similarities common to the village of the Gauls and Numantia, there are also the various Roman settlements that surrounded them.

Aquarium, Totorum, Laudanum and Compendium border the village of Asterix, but seven Roman encampments totally surrounded Numantia in the year 134 BC. General Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, hero of Carthage, used this stratagem to deliver the coup de grace to the mighty Celtiberians: by uniting the encampments with a double belt of fortifications, he cut off all supply routes to the city, which was reduced to starvation within a year.

Deprived of any sustenance or external help, Numantia fell in 133 BC, after 20 years of heroic resistance . Many surviving warriors preferred death to slavery, and according to the legend they even set fire to the city before the final defeat. This brings to an end one of the most extraordinary stories of resistance in the history of Europe, but the deeds of the Numantians will resonate for centuries in the streets of the Roman empire, reaching to the present day.

Even though various documents and books tell of this amazing tale (including El cerco de Numancia by Miguel de Cervantes, 1585, and the Spanish comics series El Jabato), there is no official evidence linking the idea of Goscinny and Uderzo to the history of the Iberian town. Nevertheless, it is clear that Asterix and the Gauls share with the Numantians an immense love for freedom, a love capable of uniting oppressed people and giving them unimaginable strength, just as the most powerful of magic potions.

Header image: [Astérix le Gaulois] © Albert Uderzo & René Goscinny / Éditions Albert René

Article by Giovanni Bonsangue