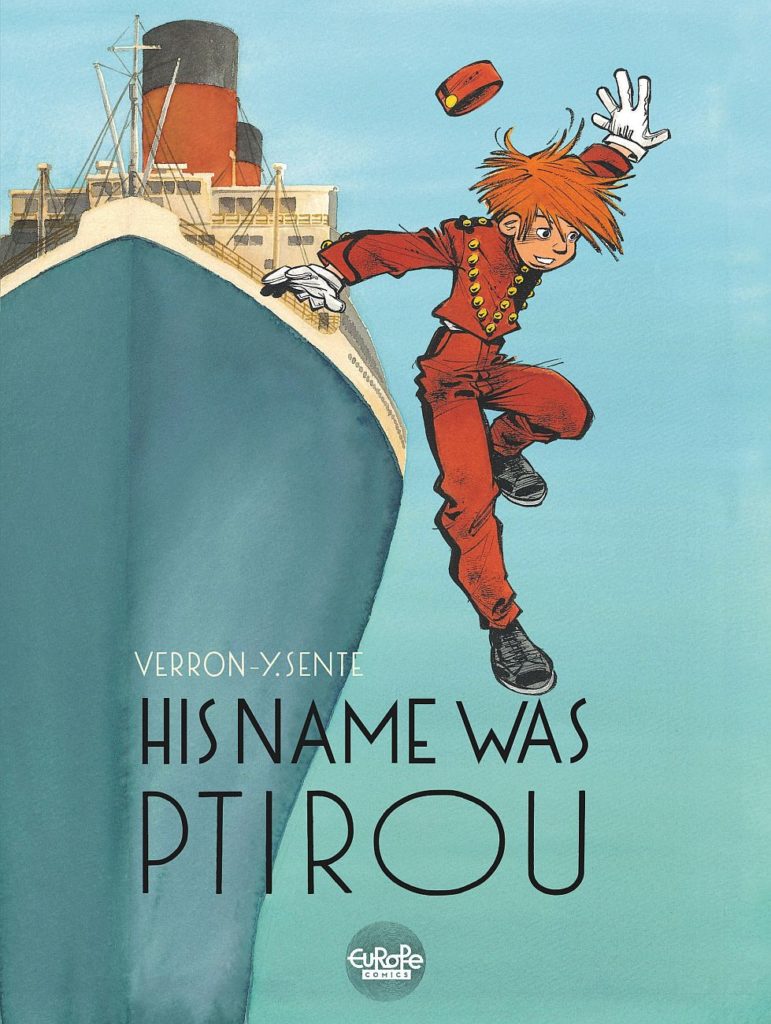

With the publication of His Name Was Ptirou, written by Yves Sente and illustrated by Laurent Verron, and the release in parallel of Emile Bravo’s Diary of a Naive Young Man (Dupuis, Europe Comics in English), we take a look back at a hero who not only hasn’t aged after 80 years, but keeps getting younger: Spirou! Here we sit down with authors Emile Bravo and Yves Sente, and Benoît Fripiat, the editor of these two books which will be delighting anglophone audiences around the world. A unique saga in the wonderful world of comics, which continues to flourish in 2019 with the release of Spirou in Berlin (Carlsen/Europe Comics), by the German creator Flix.

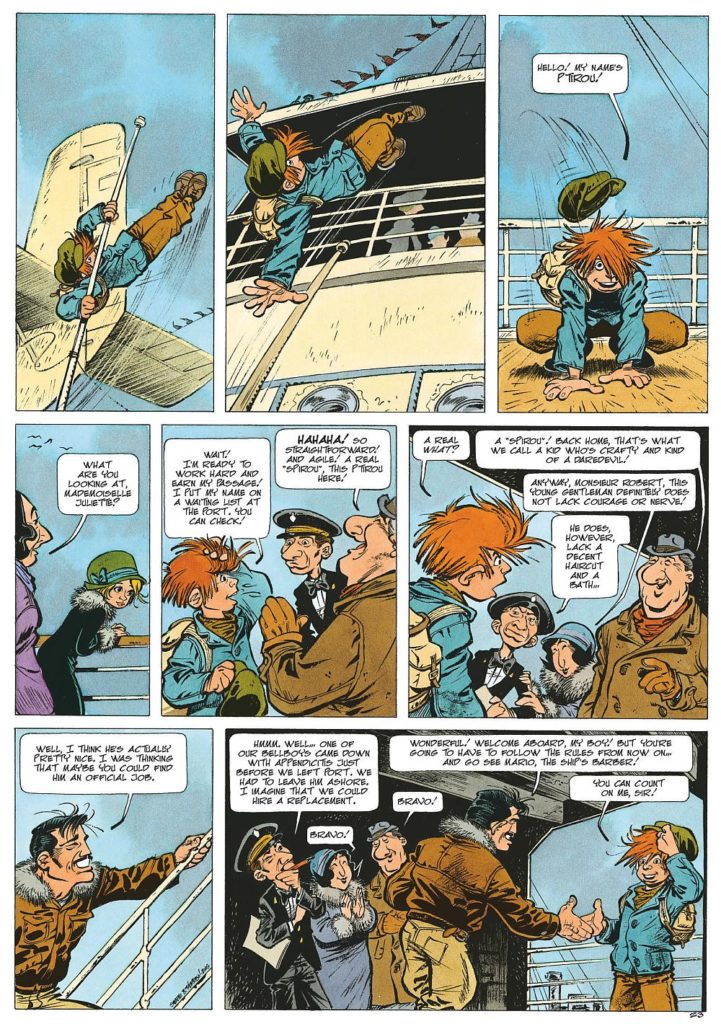

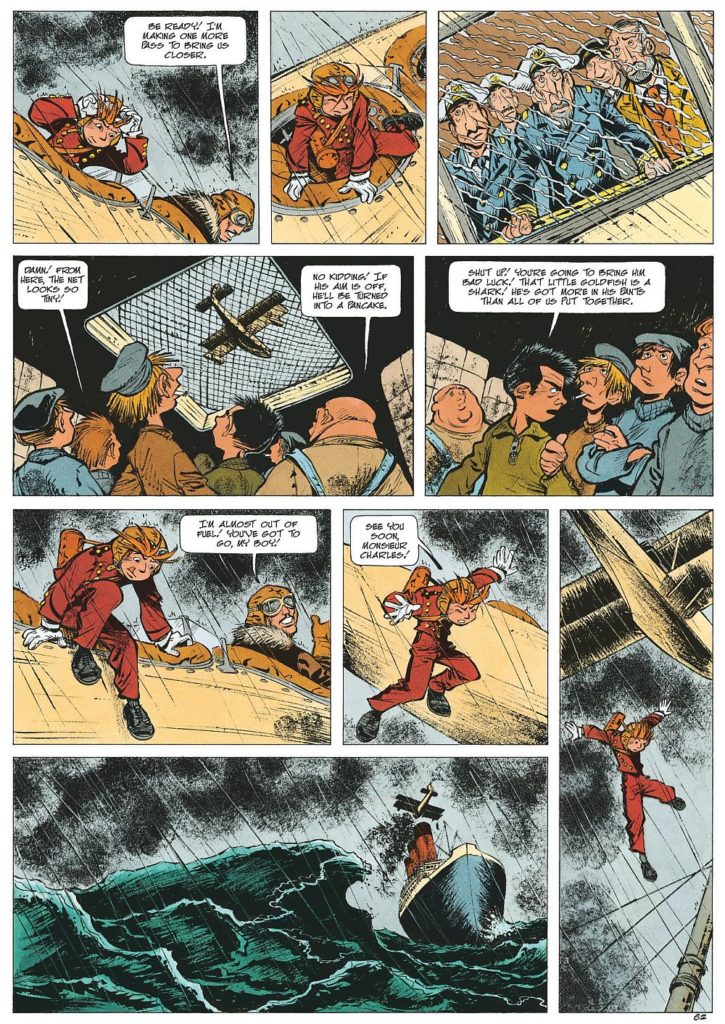

Whether by luck or sheer coincidence, these words were written on April 21, 2018, 80 years to the day after the magazine Spirou was created by Jean Dupuis, a Belgian printer and publisher working out of Marcinelle, south of Brussels. Spirou & Fantasio, Lucky Luke, The Bluecoats (Les Tuniques Bleues), Billy & Buddy (Boule & Bill), Gomer Goof (Gaston Lagaffe), and Buck Danny (all published in English by Cinebook), as well as The Smurfs (Papercutz), all found a home in the pages of the famous French-language, Belgian weekly. A practicing Catholic and an ardent believer in Europe, Jean Dupuis asked his son, Paul, to come up with a mascot for his kids’ magazine. Paul Dupuis then commissioned Robert Velter, an up-and-coming cartoonist who worked under the pen name Rob-Vel, for the task. That’s how we ended up with the image of this young, lively, and mischievous fellow, a bellboy by trade—in homage to a cabin boy who wore a red uniform and fell to his death while serving aboard the cruise ship Île-de-France, where Velter had been head steward.

A likeable, timeless character, Spirou remains the symbol of the success and good fortune of publisher Dupuis. Following his creation at the hands of Rob-Vel, the character was first entrusted to artists such as Jijé, Franquin, and Jean-Claude Fournier, and has continued to inspire a whole flock of artists over the years: Nicolas Broca, Raoul Cauvin, Yves Chaland, Tome & Janry, Jean-David Morvan & José Luis Munuera, and Yoann & Fabien Vehlmann… to name but a few! Being called upon to carry the Spirou torch has become like winning the Nobel Prize in comics.

Benoît Fripiat, an editor on cloud nine

“Spirou is the character who’s most emblematic of Dupuis, the one that started it all: the magazine, the comic albums, the cartoons. Still as central as ever after 80 years, he’s had around a hundred albums’ worth of adventures!” begins editor Benoît Fripiat. “He’s an amenable, optimistic character. Amenable, no doubt due to his origin as a bellboy, and optimistic, because he is unshakably positive. At first glance, he may seem rather nondescript, but that’s also what gives him his great potential, because each creator (or pair of creators) has been able to fashion him in his own way without betraying the original concept.”

To carry on the tradition of a cult series, to refresh it without betraying it, it’s necessary, he thinks, for the authors to have a personal—and original—vision of the character. This requires reflection, talent, and a lot of work. He tells how, in the case of Ptirou, Yves Sente came upon the idea while reading Le veritable histoire de Spirou (“The True Story of Spirou”) by Rob-Vel, the character’s creator; one anecdote in particular had moved him greatly. “He submitted his idea to Sergio Honorez, editorial director at Dupuis, who was immediately taken with his story. Yves then proposed placing the artwork in the hands of Laurent Verron, the artist for the series Odilon Verjus as well as the reboot of Billy & Buddy. Yves had already had the opportunity to work with him when he was editorial director at Le Lombard.” The illustrator was hesitant at first, not wanting to work on one reboot after another, but in the end, after reading the synopsis, all of his doubts fell away.

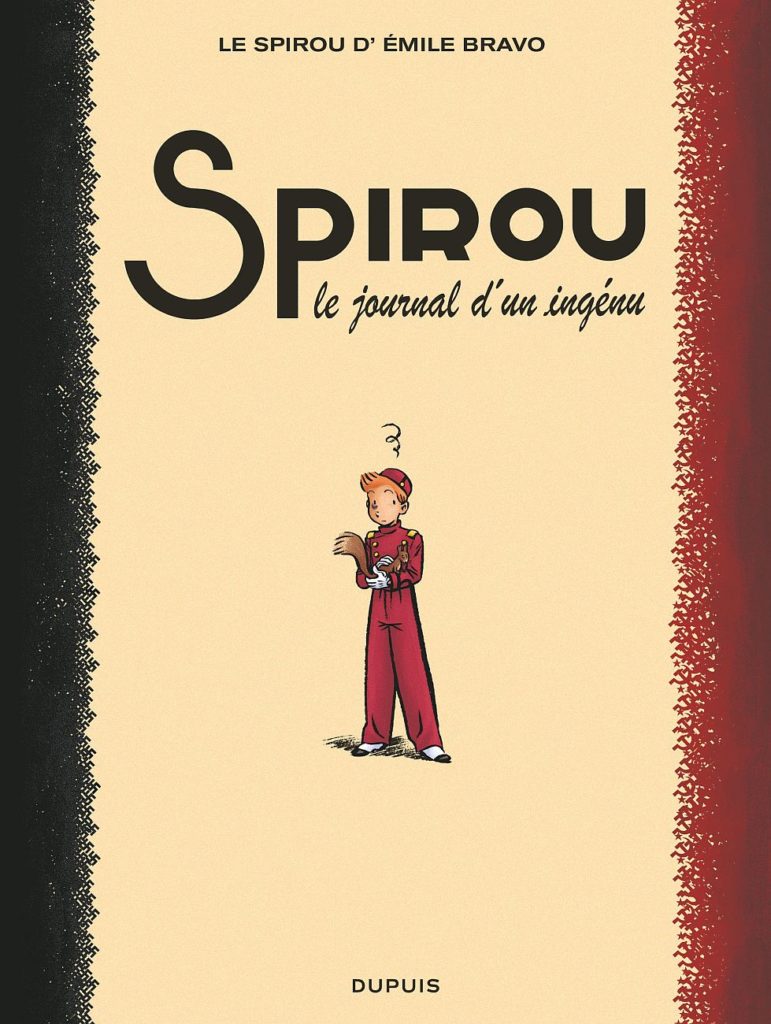

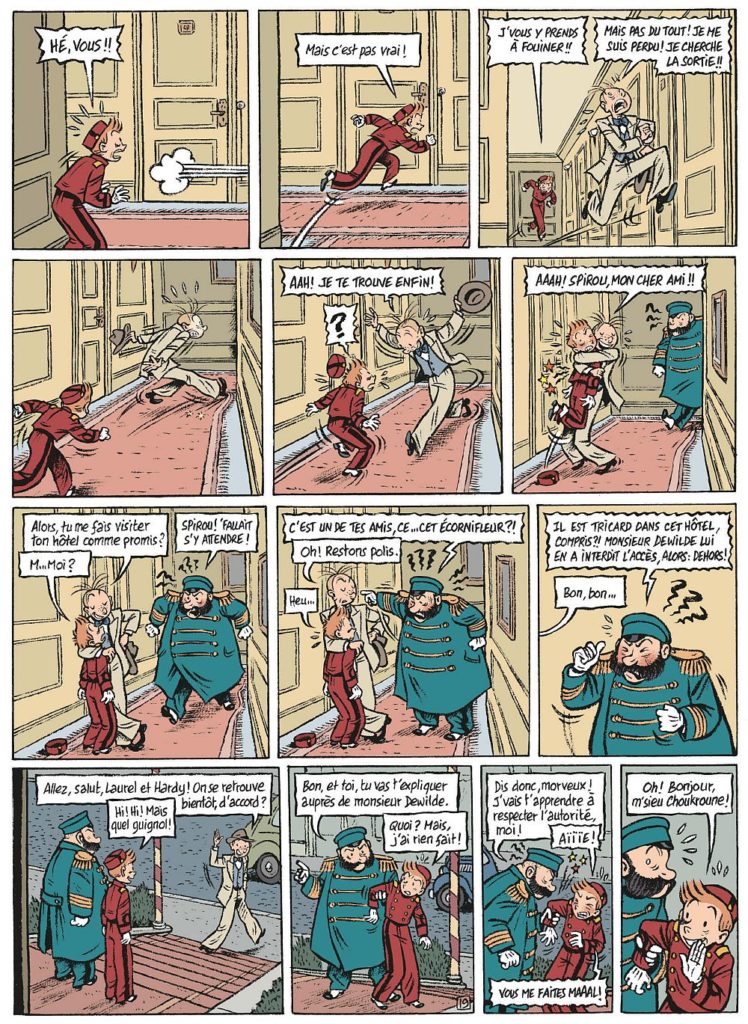

For Emile Bravo and his Journal d’un ingénu (“The Diary of a Naïve Boy”), the story starts about 15 years ago. “When I was an assistant editor at Dupuis,” recalls Fripiat, “I called Emile to tell him that I really wanted to work with him. Several years later, when the series of Spirou one-shots began, he got back in touch with me to tell me that he wanted to work on his own vision of the character.” His album came out in April 2008, and was met with great success, winning numerous prizes, including from the Angoulême International Comics Festival and RTL Radio. “Sales took off—more than 80,000 copies in the first year of its release,” says Fripiat. “That was ten years ago, and it continues to sell today.”

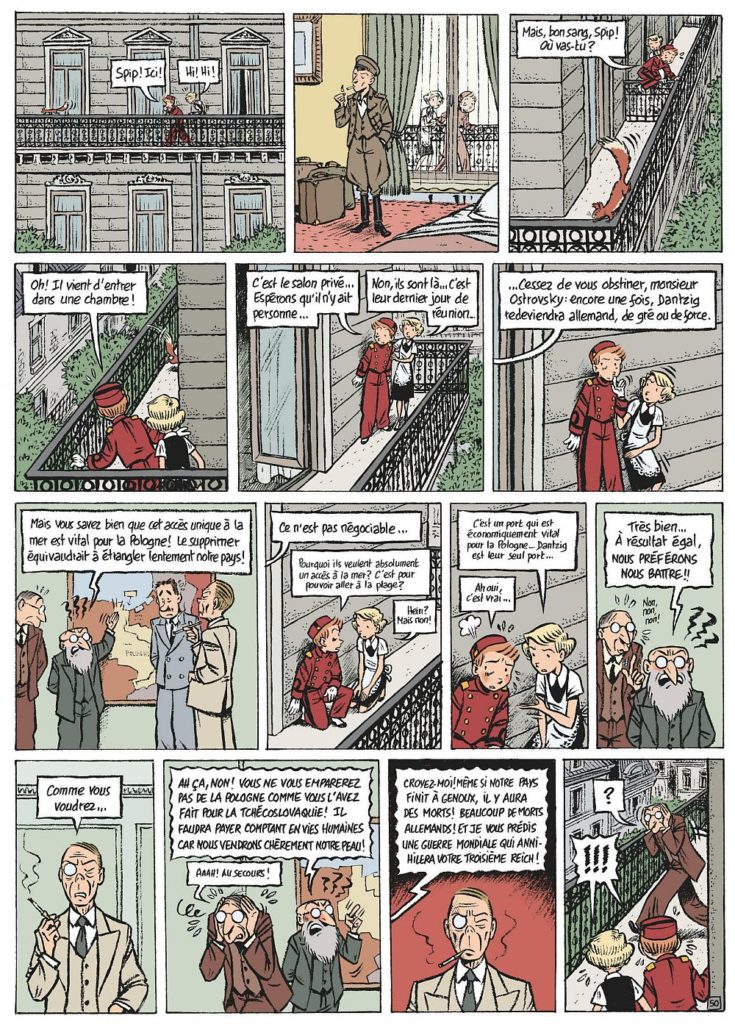

In 2014, the idea for a follow-up was born, as Emile Bravo realized he still had much to say, especially in dealing with a period as dramatic as the Second World War. After nearly four years devoted entirely to the script, the writer-artist threw himself into the herculean task of bringing the story to life, all 330 pages of Spirou ou l’espoir malgré tout (“Spirou: Hope Against All Odds”). The first of four parts will be released in French in October 2018, and it is currently in prepublication in the weekly Spirou magazine. “I’m really lucky to have such an extraordinary editor who gave me nearly eight years to complete this project. Considering the success of the first volume, the publishers aren’t too worried, but economically, it seems crazy that an editor would be so patient,” remarks the author, still amazed.

Free rein

In the case of both of these works, the authors themselves chose to explore the character’s early youth. Their editor explains: “When creators ask us if there is a guide book for illustrating or writing Spirou, we always answer: ‘You can read the albums but you are not obliged to follow everything that others before you have done.’” It’s his belief that the charm of these two albums lies in “the total devotion of authors who believe wholeheartedly in the story they are telling. There’s a sincerity which allows true emotion to be born.” He adds that “unsolicited story proposals continue to flood in, both from known and unknown artists, professionals or amateurs.” As for Emile Bravo, he emphasizes, “If I hadn’t been given free rein in making this album, I never would have agreed to do it.”

A hint of childhood

For both of the authors, the little bellboy was a childhood friend—“in the same way as Tintin and so many others,” as Yves Sente puts it. “Ptirou allowed me to dive into my earliest memories and to ‘magnify’ them in some way. Everything associated with our early childhood is timeless. Our earliest emotions stay with us until the day we die. Whether it be a story, music, a smell, or a place, anything that takes us back to childhood is precious,” remarks Sente, who finds each new story to be a challenge. “But it’s a double challenge to return and tackle a myth. You have to focus in on your instinct: would we ourselves have liked to read this story? That’s the only question to ask yourself.” Sente and Verron intend to tell the story of Ptirou’s friend, Juliette, as well: “What happened to her, ten years later? And ten years after that? We shall see…” In the meantime, Sente tells us that the most touching compliment he’s gotten so far about the album is that it brought one of his readers to tears. “The hardest thing to do in comics,” he says, “is to evoke true emotions, beyond just humor and suspense.”

Emile Bravo notes the same resonance with his childhood: “All of this is closely tied to my youth and to Franquin. I haven’t read the albums by the artists who came after him. I really did grow up with this character, who was more mischievous, irreverent, and imaginative than Tintin.” Even at a young age Bravo was very rational, and was constantly wondering about this bellboy: “Why did Spirou work in a hotel and wear such a ridiculous uniform? What sort of friendship did he and Fantasio have?” As he points out, “In Tintin, you see all the characters appear over the course of the albums, you discover their relationships, and understand why they are friends and why an old alcoholic is together with this sanctimonious young man. I had the impression that my dog could think, just like Snowy could. Which wasn’t the case with my friends, who typically had rodents—I didn’t get the sense there was much going on there. [laughs] So, in Spirou, I didn’t get why the Marsupilami couldn’t talk while the squirrel, Spip, could. I wanted answers to all these questions. Grown-up Emile wanted to explain what was happening to little Emile. That’s why I made the Spirou that I did.”

Jules and Spirou, the same struggle

With Journal d’un ingénu it was also important for Bravo to get out of the closed world of comics and revive the sort of book “that can be shared, that families can enjoy across generational lines.” It was the opportunity to get his work out there, too, in the hope that the public would discover another of his series, The Amazing Adventures of Jules (Dargaud, Europe Comics in English) often considered to be something that’s just for kids: “By going deeper into the world of comics, I wanted to show to my readers that Jules, too, is an all-ages series. For me, Spirou and Jules are the same thing. For one, the backdrop is history, and for the other, it’s science, but they’re designed in the same way. They’re part of the same body of work. In comics, the main characters are often a bit nondescript—the most important thing is what’s around them, that’s what carries the story.”

Franquin the genius

Emile Bravo appreciates every compliment he gets from his readers, but one comparison touches him more than all the rest—when he’s told by fans that they haven’t had as much pleasure reading the young bellboy’s adventures since the days of the legendary Franquin: “I think it’s because I didn’t change his universe. It’s as if Dupuis gave me marionettes to use to tell my stories, without altering that which had been done by those who came before me. Unlike Tintin, Spirou is a mascot, a kind of logo created by the authors. In the beginning, he was just there to get a few laughs, and it was really Franquin who made him into a real character. That’s why I’m interested in what came before Franquin. So I don’t alter what he did. Beyond that, if someone tells me my work is on the level of Franquin, well, of course that’s a fantastic compliment! But he was a genius, no one is in the same league as him. After Franquin,” Bravo concludes, “the mistake was often made of asking authors to take their inspiration from him and recreate his work. But in vain.”

By Loraine Adam, press attaché for the comics festival Formula Bula (Paris) as well as numerous other events in France, and journalist at Rolling Stone France, where she covers comics every month.

Translated by Tom Imber.

Header image: His Name Was Ptirou © Sente & Verron, Dupuis/Europe Comics